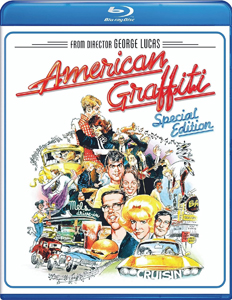

With “American Graffiti” (1973), George Lucas wanted to put 1962 in a time capsule, and he ended up creating a film that has stood the test of time. It was added to the National Film Preservation Act’s catalog in 1995 and this week is being celebrated for 50 years of influence on filmmaking.

Lucas’ most personal film

Ironically, it’s the most different film among Lucas’ directorial catalog – the other five are sci-fi films – but it’s also his most personal (even though it’s also a rare film where he’s a co-writer, sharing duties with Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck). At one point, Modesto’s reigning street racer John (Paul Le Mat) walks with Carol (Mackenzie Phillips) through a junkyard and recalls a vicious crash – a reference to Lucas’ near-fatal crash a decade earlier.

The difference in genre disguises the similarities with “Star Wars’ ” Luke Skywalker, as Curt (an appealingly smirky Richard Dreyfuss) debates whether to stay or split town on this last night before he’s scheduled to depart for college out East. Steve (Ron Howard, in his proto-“Happy Days” role) likewise has this internal debate, and they make different choices at the end. The male leads – the fourth being Charles Martin Smith’s geeky Toad – are Lucas’ personality split into four.

“American Graffiti” (1973)

Director: George Lucas

Writers: George Lucas, Gloria Katz, Willard Huyck

Stars: Ron Howard, Richard Dreyfuss, Charles Martin Smith

For all “American Graffiti’s” simplicity as a slice of life in 1962 Modesto, and for all its mass appeal, it’s remarkably influential, too. The reason why many films before this time seem to be slow-burn and plot-based is because strict linear storytelling dominated.

“American Graffiti” carved a path for multiple-storyline narratives in the mainstream. We get a bit of Curt (who accidentally gets initiated into the Pharaohs), a bit of Steve (who thinks breaking up with Cindy Williams’ Laurie is the mature move), a bit of Toad (trying to be cool with Candy Clark’s Debbie) and a bit of John (who embodies the idea that “it’s all downhill after high school” since all he knows is racing, and his title is in jeopardy thanks to Harrison Ford’s proto-Han Solo Bob Falfa). Rinse and repeat.

Interestingly, Lucas was adamant that “Star Wars” (1977) return to linear storytelling, which is why he has never restored the deleted Biggs scenes on Tatooine to a cut of the movie. Because he wanted to capture the serial style, he had each character lead to the next character – the droids to Leia to Luke – rather than breaking the flow by cutting to Luke before his linear introduction.

It doesn’t need a plot

As ubiquitous as the multiple-narrative structure is now, it was “experimental” at the time. “THX-1138” (1971) was also experimental – more interested in dystopian themes than plot. It’s notable that Lucas – proving himself as a strong character writer here — has always struggled with the detailed part of plotting (he’s better at the macro portion, a.k.a. world-building). Because of Expanded Universe stories, every aspect of “A New Hope” makes sense to me, but someone watching it for the first time will likely find it filled with, if not plot holes, under-explained elements.

One thing “Graffiti” and “Star Wars” have in common is they move so briskly – thanks in both cases to the editors (Verna Fields and Marcia Lucas on this one) – that it’s like surfing on an attitude more so than following a story. In “Star Wars,” the story is bizarre (to the uninitiated) and “Graffiti” outright lacks an overarching story.

(It has memorable snippets of story, though. Toad’s and Debbie’s feared encounter with the Goat Killer shows Lucas could’ve been a slasher filmmaker if he wanted. And the Pharaohs’ move of ripping off the police car’s bumper is an all-timer among youth-movie pranks.)

“Graffiti” doesn’t need a big plot, because the characters and after-dark cruising vibe – narrated by radio DJ Wolfman Jack (who plays himself) — is enough. John Hughes’ Eighties films and Kevin Smith’s Nineties films further built “one night of young people being young people” into a genre.

Both of Lucas’ Seventies blockbusters are long music videos, in a way, with John Williams soundtracking “Star Wars” and the radio hits of the Fifties through 1962 filling “Graffiti.” “41 Original Hits from the Soundtrack of American Graffiti” pioneered that entire category of music album.

Cruising culture

The film captures a way of life I’ve never been comfortable with, but which I find fascinating in fiction. People just do stuff for the sake of doing it. “Cruising” culture – at its height in 1962 but it carried into the Nineties, at least – consists of driving back and forth through town. Teens and 20-somethings talk to other people through their windows while driving, and girls hop into guys’ cars on a whim.

The small-town, trust-your-neighbor attitude is taken for granted (Lucas knows no other approach). Humor is gleaned from the notion of sexual assault – Carol’s threat to John of crying rape in front of a police officer – and the idea of an older guy putting moves on a 12-year-old. John uses this tactic to finally get rid of Carol, who has been his cruising passenger against his wishes. When watched today, this aspect of “Graffiti” – wherein females are indeed objectified but likewise are respected as not being fragile — is as fantastical as anything in “Star Wars.”

So Lucas’ notion of making a nostalgic time capsule a mere 11 years after the time he’s chronicling proved wise. If someone made a nostalgic film about 2012 in 2023, it would be absurd. Things got worse in these past 11 years, but gradually and boringly. From 1962 to 1973, things got worse in shocking and sudden ways, so “American Graffiti” was a poignant look at the more innocent 1962.

In 2023, the film plays as a look back at the more innocent 1962 and 1973. Despite the cultural sea changes, it still wasn’t nuts in 1973 for people to casually trust each other. Now that seems like science fiction. As for the stakes — whether to leave for college or remain a townie, and a road race that puts nothing at stake except the most important thing, pride — they become epic under Lucas’ direction.

That’s why today’s teens (and today’s people who remember being teens) will never feel totally out of touch with the bygone time of “American Graffiti.”