In Philip K. Dick’s “Minority Report,” the three precog crime-solvers are named after legendary mystery novelists: Agatha, Arthur and Dash. Agatha Christie wrote 74 novels, Arthur Conan Doyle 22, and Dashiell Hammett … cue record scratch … five.

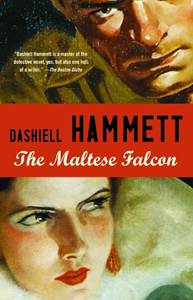

Yet Hammett is not overrated. He wrote many other things, but also, although his novel output is shockingly low, two of those novels are 1930’s “The Maltese Falcon” and 1934’s “The Thin Man” (which I’ll review in a future Sleuthing Sunday).

These are two of the genre’s most influential novels, with “Falcon” not necessarily originating hardboiled crime fiction, but certainly codifying it. The novel has influenced stories in the near century since, even in other genres (for example, “Blade Runner” in sci-fi and “Veronica Mars” in high school dramas).

(Spoilers follow.)

“The Maltese Falcon” (1930)

Author: Dashiell Hammett

Genre: Hardboiled mystery

Setting: San Francisco, 1930

A template, but not predictable

“Falcon” may be an archetypal template, but it’s also unpredictable. The opening chapter is “Sam and Archer,” but quickly Archer – although given as much facial and body-language description as Spade – is killed off. Also surprising, the actual Falcon never appears in the novel. The jewel-encrusted statue is a maguffin, but rightly a famous one, as its potential monetary value drives every character’s actions.

Like the plot, 30-something Sam Spade is an archetype but also an individual. This is the only Spade novel, and Hammett penned only four short stories about him, but his status outstrips the output because there have been so many Spade-like characters. To cite one random example, Jeff Mariotte’s “Angel” novel “Hollywood Noir” (2001) features time-traveling stand-in Mike Slade.

A male reader would want to be Spade (but is probably more likely to be the wannabe tough kid, Wilmer, or the soft opportunist Cairo). Hammett cleverly makes Spade just one notch more morally upstanding than Archer – whom Spade actually dislikes – and that’s enough to barely make him a hero rather than an antihero.

Certainly, he’s a womanizer, even by the standards of the time – although I notice that the women (secretary Effie, Archer’s wandering wife Iva, and femme fatale Brigid O’Shaughnessy) do not mind his attentions. Brigid certainly uses her feminine wiles on Spade to parry his suaveness, bravery and physical strength. And Iva aggressively desires to upgrade from her loutish husband to Spade.

Effie respects Spade’s skills but makes her own moral judgments, particularly in regard to his relationships with the other two aforementioned women. Despite being barely more than a girl (indeed, she lives with her mother), we sense she’ll stand toe-to-toe with Spade if a disagreement were to come up. Hammett sees women as feminine, but not – at the end of the day — as objects.

Clipped, yet rich with detail

The author sometimes sees women as threats, too. Spade’s resistance to Brigid’s wiles is among his strong suits as Hammett examines trust versus love in romantic relationships. Although Hammett’s hardboiled writing is clipped and to the point, “Falcon” includes an occasional blitz of a detailed paragraph.

Two stand out to me. Early on, the author describes Spade carefully rolling a cigarette, thus showing how smoking is an important aspect of his life. Later, in “Falcon’s” most important paragraph, Spade outlines to Brigid the reasons why he must turn her in to the police rather than protecting her and engaging in a relationship. Her track record is such that he can’t trust her. Whether or not he loves her is beside the point.

The Spade-Brigid relationship gets at the core of hardboiled detective fiction, wherein the love of a beautiful woman is one of the highest goals of life for a depressive, blue-collar middle-aged man. But at the same time, he eyes such a thing warily – too good to be true.

The innate tragedy of romance

Tragedy hangs over these relationships, even when they’re going well. We see it again in “Blade Runner’s” Deckard and Rachael, wherein the man-woman contrast is enhanced because it’s also a human-replicant contrast.

The template has translated well to a 21st century in which gender lines have been blurred, with some arguing that the very notion of such lines is flawed. For example, Veronica Mars loves Logan, but he’s also often a suspect in her investigations.

Despite (or because of?) the clear distinctions between masculine and feminine traits, “The Maltese Falcon” reads as well today as it did 93 years ago. It brings us back to 1930 San Francisco and the way Spade has to leave messages with hoteliers, has suspects/witnesses out of reach for long stretches, and does a lot of physical legwork in tracking people or tracking down information.

But the way cash rules everything around everyone (including Spade himself), and the way people have to be cautious about letting feelings outstrip logic, is timeless.

Sleuthing Sunday reviews the works of Agatha Christie, along with other new and old classics of the mystery genre.