Alfred Hitchcock slowly and steadily moves closer to learning how to do sound films (which, to be fair, put him in the same boat as everyone else) with “The Skin Game” (1931). It’s essentially a filmed stage play – indeed, it comes from John Galsworthy’s play – and Hitch adds little to no dynamism to the slow and steady proceedings. On the plus side, the movie doesn’t have any incomprehensible scenes like “Murder!” (1930) does.

A Hatfields-and-McCoys tale set in a British village about to exchange its natural beauty for smokestacks, “The Skin Game” is driven by an entertaining Edmund Gwenn (“The Trouble with Harry”) as the aptly named Mr. Hornblower, who is buying up all the land in the area. The long-standing Hillcrists – fronted by Mr. Hillcrist (C.V. France) – don’t want to sell to this industrialist, but Hornblower has their property mostly surrounded by his acquisitions.

The property puzzle

A key piece of land in the magnate’s puzzle goes up for auction, and in a film mostly set in the Hillcrists’ and Hornblowers’ mansions, this town-hall scene boasts some Hitchcockian flair. Hornblower, Hillcrist and their agents continually bid up the piece of land.

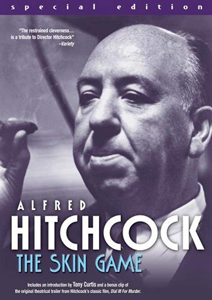

“The Skin Game” (1931)

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Writers: John Galsworthy (screenplay, play), Alfred Hitchcock (adaptation), Alma Reville (scenario)

Stars: Edmund Gwenn, C.V. France, Phyllis Konstam

Hitch wants to add humor but hasn’t figured out how to do it in the sound medium. The auctioneer clears his throat a lot, and the assistant charged with reading off the land’s specifics speaks too softly. Neither gag is funny, but the attempts at lightness aren’t as inappropriate here as in “Murder!”

Driving the back half of “The Skin Game” is a second strong – but more subtle – performance, from Phyllis Konstam as Chloe, Hornblower’s daughter-in-law. A dark secret from her past, before she went “respectable” and married Charles Hornblower (John Longden, “Blackmail”), could unravel the whole deal. Why? Because every single character behaves as if it will.

That “dark secret” is exactly what you think it would be in 1930s upper-crust British society. Today, the secret would barely be worth mentioning, let alone shameful. Still, the beautiful and glamorously dressed Konstam is so good at showing Chloe’s vulnerability as private eye Dawker (Edmund Chapman) probes her that it briefly makes this subplot magnetic.

The suspense of Chloe’s secret possibly ruining Hornblower is fair enough based on the broad rules of cinema. But if one stops and thinks about it for a second: Why should Hornblower care if Chloe’s reputation is soiled — or even his own? He’s not in the reputation game, he’s in the land-buying and industrial games. He admits as much in his early conversations with the Hillcrists where he says he has no qualms about driving them off their land.

A scandal stuck in its time

At any rate, “The Skin Game” then moves toward a moralistic conclusion that’s simultaneously predictable and unearned. It’s laughable when the industrial magnate lectures Mr. Hillcrist, who has simply been giving as well as he got. C’mon, Hornblower: Don’t hate the player, especially when you’re the one who chose this game.

Is “The Skin Game” trying to make us ashamed on behalf of Hillcrist? If so, this message certainly doesn’t land today, and it’s hard to imagine it landed in 1931.

Another flaw of the film, similar to “Murder!,” is shakiness in developing supporting players. The Hillcrist daughter is friends with the Hornblower’s other son, almost creating a tragic subplot, but not really. Part of the problem is that I never realized (till looking it up on IMDb) that Hornblower has two sons; Jill Hillcrist (Jill Esmond) and Rolf Hornblower (Frank Lawton) are the pair in this “Romeo and Juliet, But Just Friends” scenario.

The biggest thing separating these early sound works from Hitchcock’s later classics, though, is not the stories but the presentation. The tech of the time consisted of bulky cameras with short reels that had to pick up all the live sounds, since post-production sound wasn’t developed yet. There are some edits and some decent in-camera dynamics – such as when the camera swings back and forth at the auction – but “The Skin Game” only advances incrementally beyond being a filmed stage play.

This game is worth playing once for Hitchcock completists, because Galsworthy’s play is solid. The rules have completely changed since 1931, though: The “woman’s scandalous past” subplot is so stuck in its time that “The Skin Game” couldn’t be remade unless it was a period piece.

RFMC’s Alfred Hitchcock series reviews works by the Master of Suspense, plus remakes and source material. Click here to visit our Hitchcock Zone.