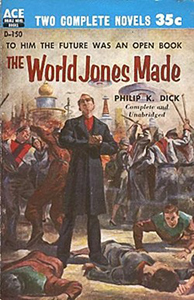

“The World Jones Made” (written in 1954, published in 1956) is among the least clunky of Philip K. Dick’s 1950s sci-fi novels. It blends the political rise and fall of the titular precog with single-celled alien drifters with quasi-human colonization of Venus. It’s wackiness quotient is lower than with most PKD books, and while Jones’ personal situation is fascinating, the political conflict is a little bland.

The illegality of lying

The story begins in the future of 2002 when the U.S. is a post-nuclear war authoritarian state. Among the new laws that even those of us in the real 2020 wouldn’t recognize is that lying is illegal. When someone is convicting of lying, they are shipped off to a forced labor camp.

Low-level secret-police officer Cussick and his colleagues give a nod to the fact that there are so many laws on the books that everyone regularly breaks a law. As such, law enforcement can decide who to arrest, and when, and what for. In regard to the illegality of lying, white lies are usually ignored. Instead, the government uses the law to stop revolutionary groups from gaining traction.

“The World Jones Made” (1956)

Author: Philip K. Dick

Genre: Science fiction

Setting: Future of 2002, United States

This is how they aim to nab Jones, a carnival fortune-teller who gains a following for speaking out against the oppressive state. The book’s title suggests that Jones creates an alternate reality in the SF sense of the term, but that’s misleading. Rather, he can see broad events one year into the future, so everything he says is proven true. Of course, the government finds some other reason to arrest him. But he gains support and then power, so in a way he does create a new world.

A second, barely connected thread shows the scientific process of preparing for humans’ colonization of Venus. This is as Clarkean as I can remember PKD getting. Even though he’s only tentatively dipping his toe into the waters of hard SF, it makes for good reading as PKD imagines that scientist Dr. Rafferty creates humanoid mutants who will be adapted for Venusian atmosphere.

Later, we see the flora and fauna on Venus itself. Granted, this is a long way from being scientifically accurate. But because Venus is the only solar system planet other than Earth that’s not a rock or a gas giant, the notion of life on the second planet must’ve been evocative in 1956, and that sense of wonder is preserved in PKD’s writing.

2 big ideas link at the end

While some criticize “The World Jones Made” for being two ideas mashed into one novel, the threads are interesting on their own and they do link together at the end. A bigger problem is that the layered political commentaries peter out. PKD has built novels around the makeup of absurd future societies, but “Jones” doesn’t dig deeply into a society where lying is filtered out of existence. (For that, we at least have the movie “The Invention of Lying.”)

The potential for humor departs along with the dropping of that thread. (PKD does drop in some jabs at inflationary currency, though, like when Cussick digs out “90 dollars in change” to pay cab fare.) Instead, we get a society that is stable because benign dictator Jones knows the future; people are comforted by this.

Meanwhile, humanity’s desire for adventure is satiated by Jones’ out-system space exploration plan, which will perhaps give answers to the mystery of the “drifters,” huge single-celled creatures that float to planets’ surfaces and die.

In part because he’s underexplored and therefore mysterious, Jones strikes me as a proto-Palmer Eldritch, someone who isn’t a god but who has godlike powers. As with Eldritch, Jones’ sees his ability as a curse more than a blessing. It’s exhausting to live every year of your life twice – going through predestined motions even as another part of your mind sneak-previews one year into the future.

Shuffling the deck of what’s legal

PKD foregrounds Cussick’s adventures as he first works against Jones and later finds himself in the rebel position as the secret service goes underground during Jones’ reign. The straight-laced Cussick is an analog for a modern social conservative, and PKD’s future Baltimore society is what modern social liberalism might look like through someone who clings to the old ways.

PKD jumps over gays and transgender people and filmed pornography. He goes straight to a stage show featuring two mutant hermaphrodite shape-changers who have sexual intercourse on stage, both alternating genders as they do so. Audience members purchase heroin and marijuana as casually as beer and wine while enjoying the show.

Cussick’s old-fashioned values are humorously illustrated when one of the performers becomes a rival for his wife’s affections. He waits until the performer shifts from a female to a male before punching him. So PKD pokes fun at one viewpoint’s rigidity and another viewpoint’s absurd ends. Hey, if a book offends both sides of the political aisle, it’s probably doing something right.

Ultimately, this isn’t as rich of a text as it could’ve been, especially in its portrayal of the anti-lying society. But “The World Jones Made” has some clever ideas and it’s one of PKD’s smoothest early SF efforts.