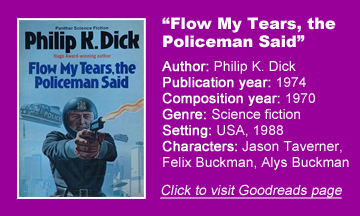

As Philip K. Dick continues his police state/drug war thematic trilogy with the second leg, “Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said” (written in 1970, published in 1974), he gets away from the dark humor and space aliens of “Our Friends from Frolix 8” (1970) and digs into this society’s impact on individuals.

Dick would mix despair and grim humor in “A Scanner Darkly” (1977), but in “Tears” he gives a straight-on portrayal of what this world is like for a citizen (Jason Taverner) and a police officer (Felix Buckman).

Surreal reality

“Tears” has a SF conceit at its core: Popular and handsome TV variety show host Taverner finds himself transported from his reality into another, where he doesn’t exist in governmental records. Later we learn this is because of a drug taken by someone else — building on the subjective-reality notion of Dick’s short story “The World She Wanted” (1953).

Yet this is one of PKD’s most grounded novels. It’s set in the near future of 1988 Los Angeles, and we know from his date-based argument with his editor over “Martian Time-Slip” that Dick deliberately picks his stories’ dates.

From his viewpoint of the 1970s, Dick knew we could accelerate to a police state with a tipping point, which in this novel is the “Second Civil War.” When read today, that off-page event is a tidy stand-in for 9/11.

Ironically, Taverner is not trying to get off the grid; he’s trying to get on the grid. This will prove to be his big mistake. A reflective Buckman notes in chapter 27 that Taverner “let himself come to our attention, and … once come to the authorities’ attention, never completely forgotten.”

It’s been said that everyone breaks three laws per day (as an example of strange laws, it’s illegal in some states to wear a mask in public, even though health officials are currently encouraging the use of masks in public). As such, the police can nab anyone any time they desire. Our main protection is simple odds: We probably won’t get picked out of the large population.

Sharp commentaries

Taverner breaks the law by purchasing forged ID cards, but Buckman later pins him for the murder of Buckman’s sister, Alys, even though he knows Taverner didn’t do it, and indeed that it was a drug overdose rather than a murder.

So why does Taverner purchase fake papers in the first place? Because as a celebrity, he is accustomed to benefiting from being known. It backfires on him only because it turns out he “doesn’t exist” in this reality. When he does exist again, after Alys dies from overuse of the drug, he can afford the best lawyers and he is found not guilty at trial.

PKD packs “Tears” with sharp commentaries like this, sometimes in sly fashion, sometimes bluntly. In the latter category are his portrayal of college campuses, which have been surrounded by police ever since the Second Civil War. If a student attempts to leave, he or she will be shipped to a forced labor camp.

In an amusing aside that illustrates the way extreme situations become normalized if they stay in place long enough, a character points out that the forced labor camps aren’t so bad. They have game rooms.

Although PKD was likely thinking of quashed Vietnam War protests on campuses (the Kent State shootings happened in 1970), I read “Tears’ ” college-to-labor-camp pipeline as a metaphor for modern real-world prospects for young people. Upon graduation, they begin the process of paying off student-loan debt.

This isn’t intrinsically bad, except that they are entering a bad economy and getting paid with debt-based currency that gets devalued more when the government attempts to stabilize the economy. Dick might have foreseen the decreasing value of a college education from his 1970s perch, but he couldn’t have predicted pandemic-based economic strife; however, it is worth noting that the US completely abandoned the gold standard in 1973.

Contrasting characters

For all its commentaries and warnings, “Tears” is most interested in exploring the impact of this world on the two main characters. Taverner, as noted, goes through a hellish but straightforward journey. The exploration of Buckman is psychological, with PKD asking himself “How does an all-powerful police general justify his actions to himself?”

Granted, if the general were cruel to his core, there wouldn’t be much to explore, but PKD paints Buckman as someone who might have a shred of decency. When Buckman cries – an involuntary act that always surprises him — it’s perhaps a symbol of his repressed morality leaking out.

That said, Buckman is no hero; he looks out for number one. He pins the murder on Taverner because he wants to maintain his position as a general in the hierarchy. Even though Taverner wins the case and the shoddy police investigation is revealed to the public, Buckman faces no personal consequences. He retires on his pension to Borneo.

“Tears” is cynical – or realist, depending on a reader’s POV – yet it has a surprisingly (but admittedly refreshing) Pollyanna epilog. Taverner not only is found not guilty, but he regains all of his fan base and then some.

In reality, it’s rare for a person, coming out of a long legal process where they are found innocent, to be embraced by society; often, they remain fairly anonymous and sometimes people maintain suspicions that the person is guilty (under the “If they were arrested they must be guilty” theory).

A free world emerges

Even more extreme, Dick tells us that the novel’s police state – and its trappings such as the forced labor camps — gradually go away with time, and a freer world emerges. In reality, states do not willingly rescind power.

This is not a case of Dick not understanding how the world works; “Frolix,” for example, takes the position that revolution or intervention by a supreme being are the only avenues for change. I suspect the author was emotionally exhausted from writing “Tears” and wanted to give us (and himself) a happy ending.

Any discussion of “Tears” isn’t complete without noting the societal taboos on display. Although this is definitely a drug novel, Dick also explores taboos that are (or were in the 1970s) much more controversial than drug use.

When Taverner accuses his lover, Heather, of having a lesbian relationship with Alys (something that happens to be true), Heather physically attacks him, seemingly because he has leveled a charge that is horrifying to speak about in polite society.

At another point, police officers mistakenly raid the apartment of a man having “consensual” sex with a 13-year-old boy; the age of consent is 12, as elite lawmakers have lowered the age so they themselves won’t be pinned. And finally, the Buckman siblings are lovers who have a child.

Codifying immorality

In 2020, the 13-year-old sexual partner and the incestuous relationship still very much jump out to a reader, and I think Dick is pointing out that an extreme police state can actually codify – or protect on the sly – things that society sees as immoral. This goes against the statist theory that laws serve to lock in a society’s moral standards.

In addition to being such a rich text, “Tears” is also a great read. The mystery of how Taverner ends up in an alternate reality is compelling (compare this to the abandoned mystery in “The Game-Players of Titan”), and the solution is fascinating: Alys’ drug use creates a temporary reality for everyone she was thinking about.

If it was – in reality — so easy to create a new world, few people would choose the oppressive state of “Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said.” But it’s one of Dick’s best-crafted novels and an important place in SF history to visit.