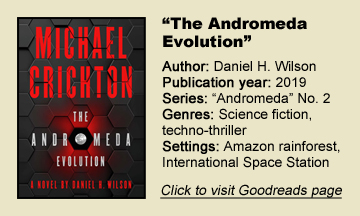

After Michael Crichton’s death in 2008, his estate and publisher found two novels – “Pirate Latitudes” and “Dragon Teeth” – to publish posthumously, plus Richard Preston finished the partially completed “Micro.” Not that Crichton’s catalog will ever stop being worthy of revisiting, but the hunger among fans for more novels remains, and I think Daniel H. Wilson’s “The Andromeda Evolution” (2019) is a neat way to satiate this hunger.

Wilson uses imagination

It helps that it’s a strong, imaginative piece of science fiction, written in the style Crichton used on “The Andromeda Strain” (1969). A tense global mystery arises around a black-walled anomaly (imagine the monolith from “2001,” but it’s a building) in the Amazon rainforest.

This object’s particles have properties of the Andromeda Strain, but it behaves differently, so scientists label it “AS-3,” following the two stages (turning blood to dust, and disintegrating latex) from the original novel.

As various military men and scientists experience or move each stage of the plot, Wilson cuts away for a paragraph here and there to deliver scientific and speculative background.

He writes in a “postmortem” reportage style, with some foreboding foreshadowing, and he includes charts and graphics and a (partially) fake bibliography, all in the tradition of the first book. It flows well.

A more diverse group

Instead of the dry, task-oriented, all-white-male quartet of “Strain,” Wilson sends a diverse group of scientists into the jungle, and focuses more on personality traits than Crichton did. Indian Nidhi Vedala leads the team, joined by American James Stone, Chinese Peng Wu and Kenyan Harold Odhiambo. Physically disabled genius Sophie Kline advises from the International Space Station.

As you can tell from Stone’s name, that’s one connection to the original novel, where Jeremy Stone was among the scientists. Another awesome yet appropriate revelation comes later.

Bigger scale

“Evolution” – like the anomaly itself – grows to be bigger than “Strain,” something that’s expected for a sequel, but readers’ mileage will vary. I dig the small-scale, realistic threat of “Strain,” and Wilson leaves that in the dust starting with a major event midway through this six-day adventure.

It’s not that the author leaves hard science behind, but he makes the situations quite complex, thus requiring him to pepper in more explanations and exposition. (After all, our heroes are in the jungle, not a lab.)

For example, Vedala has developed a repellent spray that protects people and plastics against AS-1 and AS-2, so these original strains are dangerous … yet not so dangerous. And she can’t get a sat-phone signal, yet Odhiambo is able to spell out a visible message with branches.

Later, one character’s theory about Andromeda’s evolutions stands in for the central danger. The plot outpaces the scientific study, and “Evolution’s” rapid-fire events become unwieldy.

The climax is big enough that the idea of a multi-national cover-up strains credibility. On the plus side, it’s something that you won’t see coming from early in the book.

Blend of Wilson, Crichton

Wilson’s prose is smooth, and he adds a helpful illustration of the ISS for the scenes that take place there. I could’ve gone for even more illustrations. But as the events get bigger, I was able to understand what was happening even if the details are less logistically airtight than in a top-shelf Crichton novel.

There’s a lot of Crichton DNA in “Evolution,” but Wilson also writes a Daniel H. Wilson novel, and I don’t begrudge him for that. We want more than just a stiff, straight imitation of Crichton, after all.

So what next in the realm of Crichton continuations? I’ve always wanted the story of those dinosaurs that reach the mainland in “Jurassic Park” and “The Lost World.”

The titular object from “Sphere” might still be among the wreckage at the ocean bottom. If such stories were to be done with the same sense of purpose and quality that Wilson brings to “The Andromeda Evolution,” I’m game.