The 1980s were when teens became real people, right? OK, so that’s my age bias (born in 1978) coming into play. There were 1970s films and TV about teens; I’ve recently looked at the “Carrie” novel and film in my Stephen King flashback series, and “James at 15” was the “Dawson’s Creek” of its era. Plus, “Freaks and Geeks” flashed back to that time.

I know from “American Dreams” that the Sixties had teenagers, and probably previous decades, too. But it might be awhile till I explore teen entertainment from those before-times. While the 1990s are “my” decade, and I’m proud of it, I have a thing for the Eighties too, even though I didn’t discover the films of John Hughes (1950-2009) till later.

What a time

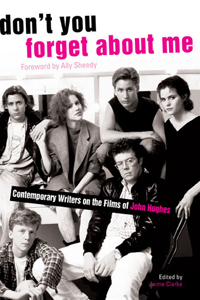

“Don’t You Forget About Me” (2007) collects 20 essays by writers who came of age around 1984-87, the time Hughes’ six high school films (“Sixteen Candles,” “The Breakfast Club,” “Weird Science,” “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” “Pretty in Pink” and “Some Kind of Wonderful”).

“Don’t You Forget About Me” (2007)

Subtitle: Contemporary Writers on the Films of John Hughes

Editor: Jaime Clarke

Although some of the essayists saw every film in theaters, this marked the first decade where they didn’t necessarily have to. They could catch up via the video store. As such, teen movies could spend a longer period in the spotlight, and be thoroughly absorbed into the zeitgeist. This crossroads of timing and art is why we think of Hughes as putting the kids in the cultural picture like never before.

I enjoyed every one of these essays, and since 12 of the writers are women (eight are men, one of whom is transgender) I learned a lot about their perspective. Indeed, I now have my answer to why “Sixteen Candles” – which I find flirts with being boring – is widely loved. Lisa Borders points out that Samantha’s (Molly Ringwald) dream of dating Jake is a universal girls’ fantasy, and Hughes tapped into a fantastical magic, clinching it with the candlelit happy ending.

Teen girls’ “slut”-“prude” dilemma (the Eighties incarnation of the Madonna-whore complex) is nicely outlined by Julianna Baggott. Ringwald’s Andie in “Breakfast Club” particularly deals with this, but it also applies to her characters in “Sixteen Candles” and “Pretty in Pink.” Interestingly, Baggott notes that the male cultural norm (“Boys will be boys”), while simpler to navigate, does not do males any favors in the long run.

The Eighties, largely credit to Hughes, rose questions of cultural expectations. Those questions were then challenged in the Nineties (“My So-Called Life,” “Buffy”) and have more recently been blown up, as films and TV about individualistic young women and men are common.

Imperfections

“Don’t You Forget About Me” isn’t filled cover to cover with fans praising Hughes for getting everything exactly right – which is a good thing. Even Ally Sheedy’s loving introduction adds to the common criticism that her character should not have been prettied up at the end of “Breakfast Club.” And John McNally reminds us that the otherwise flawless Ferris Bueller is rude to people of foreign descent.

Just as Hughes was imperfect, so are some points proffered in this collection, so let’s move on to the flaws. A couple authors cite “Sixteen Candles’ ” Long Duk Dong as a negative stereotype. I think they fail to get past his name, which of course makes us giggle because of its phonetic English meaning.

Dong is, in my opinion, the best part of the film, because Hughes highlights Dong’s admirably positive outlook on life – a foil for all the ennui-laden white American teens. Dong dates a girl he likes, not caring that she’s awkwardly tall, and he loves every moment of living out absurd but expected high school behaviors – which he can’t do in Japan.

Tara Ison states that “Pretty in Pink’s” Duckie is gay, but she never backs that up and in fact contradicts it by noting his obsession with Ringwald’s Andie. I see Duckie as a metrosexual, a fashion- and image-conscious teen boy who doesn’t fit masculine stereotypes but who is nonetheless straight. Duckie’s painful unrequited love for Andie shines through in John Cryer’s performance, making it absurd to claim he’s a coded gay character.

That said, I have wondered if Mary Stuart Masterson’s Watts in “Some Kind of Wonderful” is a coded gay female character. She interacts with another female lead (Lea Thompson’s Amanda) far more than Duckie interacts with any male character, so a cogent case could be made.

But I’m also happy to dig into essays about the beauty of Eric Stoltz’s Keith finding love with his best friend Watts at the end, rather than the traditionally desirable Amanda.

Getting personal

Many of “Don’t You Forget About Me’s” essays are appealingly personal, rather than analyses of the films. Dan Pope and Ben Schrank tell of dating girls because they looked like Hughes-movie actresses – Ringwald and Masterson. And Moon Unit Zappa chronicles her crush on Michael Schoeffling of “Sixteen Candles.”

Zappa, the daughter of Frank Zappa, explains how her bohemian upbringing was so different from the mainstream lives of Hughes characters that his movies opened up a whole new world to her. The same goes for writers who grew up poor; McNally notes the differences between his South Side Chicago and the North Side of Hughes’ films.

Allison Lynn pens a moving piece about how her mentally challenged sister lived out a “Bueller”-esque day by accident. Tod Goldberg notes that he was labeled a “retard” for having dyslexia and therefore being sent to special ed as per 1980s public-school standards; he redefined himself via fashions and attitude at each new school a la Duckie.

These essays show that Hughes bridged the gap with a wide variety of teens. I stop short of saying all teens, as “Don’t You Forget About Me” doesn’t feature writers of minority races or sexual orientations, at least not openly. But since Hughes wasn’t trying to cover anything beyond his own experience in these six teen films, the fact that he gathered so many into his camp illustrates what a natural talent he was.