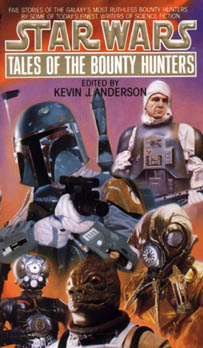

As someone who loves stories and the different ways they can be told, I’ve been smitten by “The Last One Standing: The Tale of Boba Fett” ever since its publication in “Tales of the Bounty Hunters” in 1996.

In the 63-page short story, Daniel Keys Moran intersperses an aging Boba Fett pursuing a big bounty that will allow him to retire with a bored Han Solo nostalgic for his smuggling days. The old rivals end up in an Old West-style standoff in a rundown city on a backwater planet. Neither wants to die, but neither trusts the other to lower his gun first. And then the story just ends — something I found shocking and cool at the time, and I think it still holds up.

I recently watched two movies that just kind of end in the middle of the story — “Young Adult” and “Like Crazy” — and those endings work too. When the point of the story is to capture a slice of life or complex character journeys, sometimes a pat ending is hard to come by, and a small grace note is the right choice. (Besides, “A New Hope” begins after the beginning, so “Last One Standing” might as well end before the ending.)

Moran chooses to give Fett the last word:

“Trust is hard, among enemies. Perhaps we should return to the battle; perhaps, Han Solo, we should let fly, and once more let fate decide who will survive, as we did when we were young.”

Love it.

I was inspired to re-read “Tales of the Bounty Hunters” after the recent “Clone Wars” episode “Bounty,” which features young Boba Fett, Bossk and — for the first time in the animated series — Dengar. I wanted to re-engage with these characters and also see what continuity flubs have cropped up through the years. I was surprised by how many there are. The biggest continuity gaffes (through no fault of the authors, of course) in “Tales of the Bounty Hunters” are:

- Moran says Fett used to be a rough-looking journeyman protector named Jaster Mereel, who also did a stint as a stormtrooper. With “Attack of the Clones,” we learn that his name was always Boba Fett, he’s a handsome enough fellow, and he follows his dad’s footsteps into bounty hunting.

- Moran portrays Fett as a highly moralistic, celibate loner, but Karen Traviss later establishes that Fett had a lover, a daughter and a granddaughter. Even George Lucas hinted that Fett is a suave ladies’ man by showing him flirting with a dancer in the “Return of the Jedi” Special Edition (dubbed by some of my friends back in 1997 as “The Destruction of Boba Fett’s Character”).

- Dave Wolverton, in “Payback: The Tale of Dengar,” says Dengar was injured in a swoop race against Han Solo, then had his brain worked on by Imperial scientists so he’d be the ultimate bounty hunter for the Empire. In this tale, he wonders what Boba Fett looks like under his helmet. But in “The Clone Wars,” a young Dengar is already a bounty hunter working with the young Boba Fett. And he doesn’t seem to have any brain damage, although he still wears the head wraps.

- The IG-88 assassin droid series is constructed by an Imperial during the time of the classic trilogy in Kevin J. Anderson’s “Therefore I Am: The Tale of IG-88.” But we’ve since seen IG-88 models in “The Clone Wars.”

- In “The Prize Pelt: The Tale of Bossk,” Kathy Tyers talks about Bossk building the Hounds’ Tooth to his own specifications. But we’ve recently seen the Hounds’ Tooth in “The Clone Wars” before Bossk owns it outright.

And, of course, this just scratches the surface. There are probably more contradictions — for example, from the Marvel comics, the “Bounty Hunters Wars” trilogy or “Shadows of the Empire” — that I have overlooked.

(On a side note, these bounty hunters have been defined by identity confusion ever since they were invented. Dengar was supposed to be called Zuckuss — and he was, in one comic strip — but he became known as Dengar because that’s how the Kenner action figure was labeled. Furthermore, Kenner also flipped the names of Zuckuss and 4-LOM. That gaffe did not become canon, however, because 4-LOM obviously needed to be the name of the droid and Zuckuss the name of the humanoid. Nonetheless, my childhood memory of Zuckuss being the droid and 4-LOM being the Gand is so ingrained that I sometimes had to stop and remind myself who is who while reading “Of Possible Futures: The Tale of Zuckuss and 4-LOM.” Fortunately, the other three bounty hunters have been named consistently from the start.)

Still, this book is just plain good reading. Behind the brilliant Fett’s tale, Dengar’s tale ranks second; after the surgery, Dengar is left with only three emotions — rage, hope and loneliness — and it makes him a sympathetic character.

“The Tale of Bossk” ranks solidly in third place, as Tyers nails the Trandoshan’s personality. Getting into his head is a creepy reptilian experience, as we see clearly that he cares for nothing and no one other than The Hunt; Wookiees, for example, are just pelts to him. Tyers also gives the Hounds’ Tooth a lot of character — it drugs people with needles in mattresses, it’s equipped with a creepy skinning bay, and it’s lit dimly as per Bossk’s eyesight — which is cool because bounty hunter fans tend to be fans of the ships, too; in this collection, we don’t get as much insight into the IG-2000, the Punishing One, the Mist Hunter or even the Slave I.

IG-88’s tale and “The Tale of Zuckuss and 4-LOM” came off a bit cartoony to me on this read. IG-88’s yarn plays like a dark comedy, as the IG-88 series (four droids that share the same mind) attempts to violently take over the galaxy, eventually ending up as the second Death Star’s brain.

Zuckuss’ and 4-LOM’s tale, penned by M. Shayne Bell, explores 4-LOM’s burgeoning sentience that comes about via his observation of his Gand bounty hunting companion. Interestingly, Zuckuss and 4-LOM end up firmly on the side of the Rebellion by the end. Whereas IG-88 and Bossk are clearly bad guys and Boba Fett and Dengar are somewhere in the middle, Zuckuss and 4-LOM ultimately lean toward the good side.

Although the overwriting of these tales in “The Clone Wars” and other fiction somewhat diluted my enjoyment of “Tales of the Bounty Hunters” on this re-reading, I can’t hold it against the book too much; it’s the not the authors’ fault that Lucas wasn’t sharing back in ’96.