“We Need to Talk About Kevin” (2011) possesses two endearing qualities. (Three if you count the title.) The first is the prowess in visual storytelling by director Lynne Ramsay and editor Joe Bini. Especially in the first eighth or so of the film where the eponymous villain is himself nonverbal, talk is almost unnecessary; the succession of images presents the narrative concisely with very little dialogue, the “Talk” in the title notwithstanding.

Perhaps, the title suggests, a bit more talking would have been advisable, if not by Kevin, then about him. Regardless, the wordless storytelling is superb.

The second outstanding quality is the bewilderingly good Tilda Swinton. As Eva, Swinton evokes the deep angst of a trying motherhood. It must have been a chore to maintain that level of perturbation and disquietude over so many scenes. (Luckily, it was a quick film to shoot.) She also manages to demonstrate a mother’s loyalty and bond to her child, even to one who has gone as horribly astray as Kevin. Her despondent performance is exceptional.

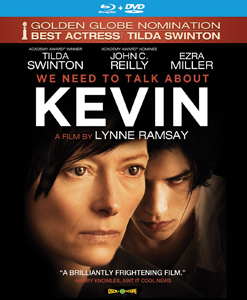

“We Need to Talk About Kevin” (2011)

Director: Lynne Ramsay

Writers: Lynne Ramsay, Rory Stewart Kinnear, Lionel Shriver

Stars: Tilda Swinton, John C. Reilly, Ezra Miller

What horrible act will Kevin commit?

Alongside the admirable aspects lies a major flaw. “WNTTAK” suffers from a simplistic structure that renders the film prosaic as soon as the structure becomes apparent. And it becomes apparent within 10 minutes or so.

We are shown the horrified faces of those who have witnessed Kevin’s crime, but we’re not allowed to see the crime itself. We have to wait until the conclusion to see what Kevin did. The remainder of the film shows two progressions, one leading up to the crime, and one unwinding from it.

The first progression shows Kevin growing up as a kid without a gram of empathy, underscored by his mother’s ineffectual attempts to draw out even a hint of humanity. The second shows Kevin in jail, his mother’s wordless visits, and the cruelty with which a community blames the mother.

The effect is relentlessly monochromatic: Kevin did something very bad. And if what we’re shown isn’t even worse than what we’ve tried to imagine, we’ll be disappointed. It’s not enough to warrant the viewer’s investment.

It’s sort of like a murder mystery wherein we know that the identity of the culprit will be revealed, but we don’t know who it is, and there are numerous clues and false leads along the way. But in “WNTTAK,” we know who did it. There is no need for clues. (We do get a couple – a lawn sprinkler whirring motif and Kevin’s penchant for archery.) Sticking with the film becomes a chore. It’s not dull, but it is wearying.

We need to talk about what went wrong with Kevin

“WNTTAK” can be categorized as an “evil kid” flick. Films with this shared heritage include “The Bad Seed” (1956), “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968), “The Omen” (1976), “The Good Son” (1993), “Orphan” (2009) and “Sinister” (2012).

Generally in an evil kid film, there is an explicit etiology for the child’s malevolence, and most of the time, it’s essentially an external evil germ. An evil force made the kid evil. Evil infected him or her. It’s Satan, witches or an abusive foster parent. Evil kid films are fairy tales that teach by allegory; they don’t suggest that the problem of disobedient kids is witchcraft, per se, but rather that external causes — neurological, spiritual or societal — are like intruders.

In “WNTTAK,” however, there is no etiology for Kevin’s vacancy. It’s not nature, it’s not nurture (nor lack thereof), and it’s not a Ouija board. No one and no thing is to blame. There simply is no reason that Kevin is psychopathic. When his mother asks him “What’s the point?” he easily replies, “There is no point. That’s the point.”

Pointlessness seems to be the point of the film. The etiology of tragedy is the same as the modern conception of existence: It’s meaningless. That seems like a predictable modern take on the evil kid plot. Evil kids just are. Suffering is as random and purposeless as existence itself. We live in a proudly nihilistic age. But it’s hard to make a film about meaninglessness without the film feeling, well, meaningless.

We also need to talk about the surprising spark at the end

Stick with “WNTTAK” to its very end, however, and there is something more. After the big reveal of the mass tragedy event, Kevin lands in prison. Eva descends to even greater hopelessness, marginalization and isolation. Neither character could sink any lower. Then there is a final scene in the visiting room of the state prison.

In the unnaturally lit room, the “why” is restated. And something rather unexpected happens. It’s not a big moment, it’s a quiet one, a plagal cadence. It hints at a theme that nothing in the preceding narrative could lead one to expect. It’s unjustified, but fitting.