With the second season of HBO’s “Westworld” set to debut on Sunday, I thought it’d be fun to finally watch writer-director Michael Crichton’s 1973 film that launched the franchise. The movie is well-known among sci-fi geeks, one of those classic dystopian visions that were popular in the wake of ’Nam. Yet it seems to be under-viewed and was therefore ripe for the TV re-imagining.

While the movie is visually dated – the theme park’s inner sanctum has a starkness similar to the adaptation of Crichton’s “The Andromeda Strain” from two years prior — it’s remarkable how little updating of the template the HBO series had to do.

‘This place is fun!’

“Westworld” starts with repeat visitor John (James Brolin) taking his friend Peter (Richard Benjamin) to the titular theme park. Skeptical at first, Peter admits “This place is fun!” after a night with a robot hooker. Soon, Peter blows away the robot gunslinger (Yul Brynner, enhanced by creepy contact lenses) and the duo explosively breaks out of the Westworld jail and rides into the desert to have a laugh.

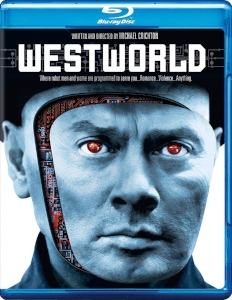

“Westworld” (1973)

Director: Michael Crichton

Writer: Michael Crichton

Stars: Yul Brynner, Richard Benjamin, James Brolin

Unlike most Crichton films, there is no accompanying novel; this was a film all the way. One can imagine Crichton was thinking of how to use existing backlots without having to spend a lot more money. Westworld features Western World, Roman World and Medieval World, all looking exactly like you’d expect.

The ideas are rich, though. This might be one of the earliest “meta” movies, as many scenes comment on film clichés even as our protagonists have a blast acting them out. A barroom brawl scene is accompanied by playful music and a grinning Peter and John. Peter’s night with the prostitute is aurally paired with a gunfight outside, as a bank robbery is in progress; the clichéd and over-the-top sound effects enhance the parody.

Early interest in chaos theory

As is almost always the case with Crichton, he explores the dark side of technology in one of those plots where things gradually go more and more wrong. Westworld, when it is fully functioning, is completely wonderful. The flip side is: When it’s not functioning, it’s utterly deadly.

The writer shows early interest in chaos theory in “Westworld”: The more complex a system, the more likely it is to break down, often in darkly ironic ways. For example, the electronic doors don’t work when the power goes out, thus locking everyone in a room, a reverse of a tense situation in “Jurassic Park” where the steel doors can’t be locked to keep out killer dinosaurs.

One park official compares the spread of the robots’ glitches to a human disease. After all, these robots were built by other robots, so the humans who run the park are learning how they work the same way a scientist learns how the human body works.

Westworld employs no one who knows how everything in the parks works. This is often a positive aspect of technology and complex systems; Joe Schmo need not understand them to benefit. But Crichton is here to remind the human race to not get cocky.

Technobabble

“Westworld” has a lot of technobabble that the HBO series has smartly filled in with mysteries and character arcs. The film cuts away from John and Peter’s adventures to have the camera pan along a row of computer technicians spouting gibberish, apparently remotely adjusting the robots’ programming to suit the specific needs of the guests. The Westworld employees work on 1973-vintage computers, and reel-to-reel tapes spin on the walls.

Mirroring one of the TV show’s favorite mysteries, there is one moment where it seems a park worker could be a robot and not know it: He is shot by the gunslinger, and that should not be possible if he is human, as the guns are only supposed to work on cold targets. I think that might be a continuity glitch, though.

By and large, Brynner and the other actors playing robots purposely tip their hand to the audience; those contact lenses help sell it. The gunslinger is not meant to seem human any more than Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Terminator is. He moves stiffly, and when we see his point of view, it’s pixelated, like an old video game.

The movie doesn’t ever challenge us to sympathize with the robots; even the fix-it stations and the nightly pickup of corpses are darkly comedic. In the TV series, those scenes are sad because we have been shown the robots’ similarities to humans — a way to dig into the question of whether biology determines humanity.

Crichton’s 1973 film is a great launching pad, though, and it holds up today as a fine piece of entertainment, even if it’s not nearly as mind-bending as the HBO series. (For those who want to dig deeper into the roots of “Westworld,” the first movie was followed by a sequel, 1976’s “Futureworld,” and a short-lived TV series, 1980’s “Beyond Westworld.”)

Click here to visit our Michael Crichton Zone.