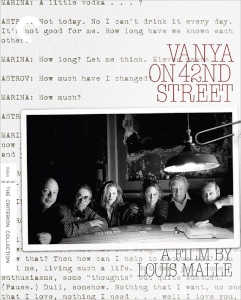

“Vanya on 42nd Street” (1994) is structured unlike anything I’ve seen before. It starts with the actors walking along the packed sidewalks of the Big Apple to a decrepit abandoned theater where they are rehearsing “Uncle Vanya,” David Mamet’s translation of the 1898 Russian play by Anton Chekhov. But then we – along with a few friends of the play’s director, Andre Gregory – are soon watching the play itself, in its entirety.

It’s a play, but not totally

But it’s not really a play. It’s a movie on a stage, a movie without sets and locations, or an enhanced play. Any of those terms would work, because the actors (many known for their screen work, although they all have stage experience, too) use movie techniques under the guidance of a movie director (the legendary Louis Malle, in his final film). The actors are in movie-style makeup and are allowed to play quiet, intimate scenes rather than projecting to the back row.

Befitting a play, there are no time jumps – no jump cuts, inline cuts, smash cuts or wipes to the next scene. But there are plenty of cuts to close-up reactions, and there are no show-offy long takes. It’s also a “rehearsal,” so we see an “I Love NY” paper cup and hear the street sounds from outside, and between acts, the actors mingle with the small audience of invitees.

“Vanya on 42nd Street” (1994)

Director: Louis Malle

Writers: Anton Chekhov, David Mamet, Andre Gregory

Stars: Wallace Shawn, Phoebe Brand, George Gaynes

None of these trappings, which sound pretentious when described, distract from “Uncle Vanya” itself. In fact, the bare-bones approach and reminders that we’re watching a “play rehearsal” smooth out any nagging questions of time and place, contemporize the material and allow us to focus on the mesmerizing performances.

Dripping with ennui without being over the top, “Uncle Vanya” chronicles the sprawling household of Serybryakov (George Gaynes, Punky Brewster’s foster dad). The people living under this roof question the decisions they’ve made that have brought them to their current point. Yelena (a glowing Julianne Moore) is married to the older and sickly Serybryakov, and although she initially married him out of what she thought was love, she admits to the man’s daughter, Sonya (a revelatory Brooke Smith), that she longs for a younger husband.

I like Moore’s acting choice where she regularly employs her big engaging smile, but it’s toward the goal of smiling through her unhappiness. Sonya, for her part, is in love with refined family doctor Astrov (Larry Pine, another actor who I’m surprised isn’t more widely known).

Achingly pure turn by Smith

Smith gives an achingly pure portrayal of the all-consuming and embarrassing pain of unrequited love, caught between the reasonable assumption (based on his behavior) that Astrov doesn’t love her and that tantalizing hope that maybe he does.

Uncle Vanya himself (the outstanding Wallace Shawn, whose most popular mainstream role is his turn in “The Princess Bride”) is in love with Yelena. “Vanya” isn’t all verbal self-analysis; there are also plenty of less-analytical moments (another thing that can’t be done as easily in plays) such as characters sharing a laugh about how ridiculously unhappy they are. After all, everyone is genuinely friends or loving family members with everyone else, even as the cauldron bubbles.

“Uncle Vanya” is set in a time and place of micro-fiscal enclaves and social-status-based employment. So Vanya is dependent on brother-in-law (via a previous marriage) Serybryakov, whom he believes never earned his renowned status as an academic on merit.

Serybryakov is dependent on Vanya in the sense that Vanya gives all of his earnings to the estate, and then gets a small salary from the estate in return. Serybryakov’s daughter, Sonya, is in the same boat. Ironically, Vanya and Sonya handle the books, so they could raise their own salaries, but they’d feel like thieves if they did so.

This precise economic situation doesn’t have an obvious modern parallel; Mamet translates it fairly straight from Chekhov’s work, I assume. That element prevents Mamet’s “Uncle Vanya” from being made into a contemporary film. It would have to be a period piece in 19th century Russia, which would be expensive, and that would still leave the question of whether American actors with American accents should play these roles.

Old Russia vs. modern NYC

But “Vanya on 42nd Street,” by retaining the “I Love NY” cup and street sounds, nudges us to draw parallels between “Uncle Vanya” and modern times. The unrequited loves and life regrets are universal and timeless. The economic situation is of its time, but the way Vanya feels screwed over by Serybryakov is relatable.

“Vanya on 42nd Street” cuts corners, but the way it cuts corners is so artistic that I not only forgive it but I think it’s a smart piece of meta-commentary from before meta-commentaries became widespread. I also have a soft spot for the architecture of old theaters, so even the run-down backgrounds – in lieu of set dressing – work well here.

Similar to what Mamet would later do with “The Winslow Boy” (1999) – making it into a film because it’s cheaper than a run of plays – Malle and Gregory (who writes the between-acts interplay in addition to acting as the play director) bring “Uncle Vanya” to a wider audience than if it was confined to the stage.

I imagine there are purists who argue “Vanya on 42nd Street” bastardizes what theater is while pretending to celebrate it, but I think the mixing of media enhances the piece while also solving the logistical and cost issues.