“Halloween” (1978) is often cited as the first modern slasher movie, but it didn’t emerge out of nowhere, with no influences. One of its most notable progenitors, well regarded among horror fans but not given enough credit in the wider world of film criticism, is “Black Christmas” (1974). Written by Roy Moore and directed by Bob Clark (“A Christmas Story”), it does everything “Halloween” would later do, but better.

A darker kind of Christmas story

Clark starts by contrasting the warmth of a Christmas-decorated home with the frigid outdoors. It’s a huge sorority house that holds 10 students and a house mother, but when it’s filled with partying college kids and Christmas tunes, it feels cozy. Outside, from a first-person perspective, a heavily breathing man climbs the trellis and gets in through an attic window.

After the party guests leave, the house — which is also the film’s best character — becomes fascinatingly foreboding as we’re introduced to its many split levels and nooks and crannies. While it’s true that Clark uses that trick where a victim’s screams occur simultaneously with other noises (party revelry or carolers hitting the high notes), the most remarkable trick about “Black Christmas” is that it’s believable that the killer is hanging out in the attic the whole time.

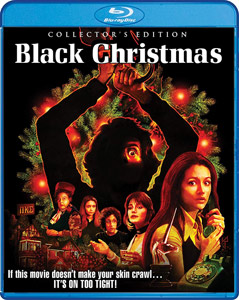

“Black Christmas” (1974)

Director: Bob Clark

Writer: Roy Moore

Stars: Olivia Hussey, Keir Dullea, Margot Kidder

This gives the film a consistent creepiness that’s missing from “Halloween,” where there are moments of safety. “Black Christmas” has a long stretch between the first and second murders yet it gains rather than loses momentum. We long to return to the relative warmth from that introductory party, but can’t shake off the chill.

Mr. Harrison (James Edmond) comes to campus to pick up his daughter Clare (Lynne Griffin) for the holiday, and we follow an entire “missing girl” plotline while knowing that Clare’s corpse — with a plastic bag over her face — is sitting in a rocking chair in the attic. There’s no mystery for the viewer, but it’s literally and figuratively chilling to know that the search party will find nothing in the woods.

During that time, the house — populated over Christmas break only by three sorority sisters (as far as they know) — becomes creepier. Clark demonstrates that if a passerby were to look closely, they could see Clare’s corpse in the window. But no one is looking in the house itself, and that’s logical.

No iconic mask yet

Perhaps the reason “Black Christmas” is mentioned less than “Halloween” among slasher legends is that the villain doesn’t wear an iconic mask. (“BC” also didn’t lead to a bunch of sequels, although it spawned a remake in 2006 and again on Friday.) Yet it masters the tactic of “the less you know, the creepier he is.”

The least likely part of the film is that there’s a separate telephone line in the attic. (It’s totally worth it for the “The calls are coming from inside the house!” moment, though.) Still, the fact of an attic phone — even though it may be clunky writing by Moore — raises interesting questions. Maybe this isn’t a random house to the killer; maybe he used to live there.

I also got a vague sense that boozehound house mother Mrs. Mac (Marian Waldman) might be related to the killer. As the killer’s prank calls escalate, we hear conversations between “Billy” and “Agnes.” Along with the “corpse in the chair” image, a viewer can’t help but think of Norman’s split personality in “Psycho.” Maybe Mrs. Mac is Agnes.

The lack of any evidence whatsoever of Billy’s and Agnes’ identity is what makes “BC” so chilling. Even John Carpenter’s famously sparse “Halloween” tells us more about Michael Myers’ background than this film does about Billy’s.

Who can you trust?

“BC” also features a trope that “Scream” (1996) would pick up: the boyfriend who can’t be trusted. In this case the players are Jess (Olivia Hussey, with an unexplained English accent that gives her intrigue and gravitas) and Peter (“2001’s” Keir Dullea). (Paving the way for shows like “Beverly Hills, 90210,” Dullea was nearly 40 when he played this college student.) She wants to abort her pregnancy and get on with her young-adult goals; he wants to get married and start a family.

Acting unhinged over this disagreement, Peter becomes a suspect in the eyes of Lt. Fuller (John Saxon). Again, this is a nice bit of logic in Moore’s screenplay: The lieutenant is going down the wrong path, but it is the wholly logical path.

As a bonus, “BC” might be the best film at showing what tracing a phone call looks like. A police officer runs around rows of phone lines at the switching station, looking for what line is in use. This may or may not be accurate, but it’s yet another example of the film’s tension, as Jess needs to keep the prank caller on the line long enough for the trace to be made.

Forty-five years later, “Black Christmas” stands as one of the elite Christmas horror movies. Before the term “slasher movie” was coined, Moore and Clark delivered an almost perfect example.