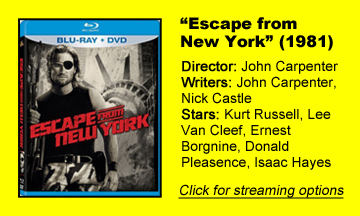

I appreciate “Escape from New York” (1981) more as an influential piece of history in the action genre than as a film that stands the test of time. It has two undeniably iconic aspects. First: the gritty, dark cinematography by the legendary Dean Cundey, which turns 1981 St. Louis into the dystopian future of 1997 Manhattan.

And second: the eye-patch-wearing, gruff-voiced, take-no-crap Snake Plissken. Kurt Russell does a lot more with this role, to darkly comedic effect, than what’s on the page from John Carpenter (who also directs) and Nick Castle – although they do give him some great one-liners to work with.

A dystopian 1997

Dystopian future dates that have since passed, and weren’t nearly as bad in reality as in the film, are always hilarious. But the 1997 of “Escape” is particularly funny. Late in the film, Hauk (Lee Van Cleef) – who remotely directs Snake’s mission to rescue the president from the walled-off prison colony of Manhattan Island – uses a cellphone as big as his arm.

It’s my understanding that no one treated this film as a comedy, but it’s often hilarious, both in its “future” tech (see also giant monitors of inexplicably blinking lights in the control center, and also laser guns!) that hasn’t aged well and in the intentionally ridiculous plot.

We don’t see the mainland of “Escape,” but I assume it must be pretty bad – although not as bad as Manhattan itself, since the prisoners want out. A terrorist crashes Air Force One into the prison island as a message to the imperialist USA.

I suspect Carpenter and Castle added the fact that the president (Donald Pleasence) has a cassette tape with a nuclear bomb formula (or something like that) to explain why officials would bother rescuing him, rather than simply promoting the vice president to the top job.

All Plissken asks for is “a little human compassion” after one of Hauk’s reminders that Snake will be dead (there’s a mini-bomb in his neck) if he doesn’t complete the mission on time. And Carpenter – who also co-writes the classic 1980s-style synthesizer score – thoroughly illustrates a world where no one gives a rip about anyone else.

He used to care

The former war hero Snake is underwritten, but at the end we learn some of his motivation for attempting to rob a Federal Reserve branch (go big or go home, apparently). He asks the prez his thoughts about the people who died rescuing him, and his expressed condolences are less than convincing.

Snake walks away in disgust. He doesn’t “give a f*** about your war, or your president,” but that strong sentiment grows out of the fact that he used to care. This is “First Blood” Lite, but “Escape” did come out a year earlier.

Plus, I like how Snake is less of a superhuman than John Rambo would end up being; with multiple arrows in his leg, he limps his way through the second half of this film. He presages John McClane from “Die Hard” (1988), another action hero who absorbs injuries in a realistic manner.

A straight line can be drawn from “Escape” through 1982’s “First Blood” and “Blade Runner” to 1984’s “The Terminator” – all grime-covered action classics that use practical stunts and effects. James Cameron worked in the visual effects and matte departments on “Escape.”

Rough around the edges

But while Cameron’s “The Terminator” is a perfect example of this subgenre, “Escape” is rougher around the edges. “Alien’s” Harry Dean Stanton has a supporting turn as The Brain, who works for The Duke of New York (Isaac Hayes), but I didn’t grasp what his aims are.

The Brain knows the locations of the mines on the bridge that leads to the wall where Snake and the prez will make their escape. But when he announces the mine locations amid their journey, he’s wrong and he gets blown up.

More broadly, “Escape’s” world is unsurprising once we’re immersed in it. This criminal-run city is exactly what you’d think it would be. We’re seeing the most crime-ridden portions of big American cities – exaggerated, sure, but not by a lot. The most extreme creation is the Crazies, who come up from the sewers at night; it’s briefly implied that they are blind, perhaps a nod to their underground lives.

When thinking back on this film, a viewer can imagine that the New York of this world is in a perpetual night, similar to the L.A. of “Blade Runner,” although it does briefly turn to day at one point. The aesthetic of this film is iconic – if you say a rundown area of a city looks like “Escape from New York,” everyone knows what you mean.

And Snake remains the most legendary role of Russell’s impressive career; it’s a shame we only got one more film with him (1996’s “Escape from L.A.”), as Carpenter apparently didn’t have any ideas (or desire) for expanding Plissken into a full-fledged antihero action franchise.

Still, among the oft-cited gritty dystopian films of the 1980s, “Escape from New York” is shorter on rewatch value than its contemporaries.