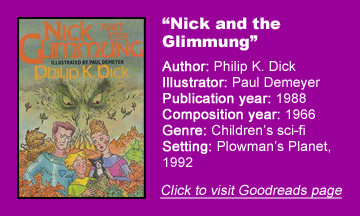

A couple years before writing “Galactic Pot-Healer” (1969), Philip K. Dick invented that story’s world (Plowman’s Planet) and villain (Glimmung) in the children’s novel “Nick and the Glimmung” (written in 1966, published in 1988).

Although Wikipedia says the two books are set in the same continuity, I find it to be more of a case of Dick recycling names, as he does throughout his career.

A new Glimmung

Despite the title, the Glimmung is always referred to as Glimmung, as if that’s his name, not his species. In one of the book’s five illustrations (the cover and four inside), Paul Demeyer draws Glimmung in bipedal form, like an ancient stone warrior from the sky.

“Galactic Pot-Healer’s” Glimmung inspired at least one cover artist to draw a Lovecraftian one-eyed, tentacled creature. Also in terms of narrative flow, the two stories don’t cleanly line up.

Perhaps owing to his target audience, “Nick and the Glimmung” spells out sides of clear good and clear evil, with Glimmung among the latter group.

“Pot-Healer’s” Glimmung is one of those intergalactic creatures with near godlike powers, and his aims are obscure, although he comes off as more self-interested than outright evil.

Creature creations

At 121 pages, “Nick and the Glimmung” is easy to read, but not among the most compelling of PKD’s longer short stories. I can imagine it would spark some imagination in sharp young readers who enjoy the various creatures on Plowman’s Planet, who Dick recycles from his other works — although again, it’s mostly the names his re-uses.

Wubs are friendly and dumb haulers, spiddles are elf-like helpers, father-things are plants that grow into deceptive copies of real people, werjes are flying nasties who can be staved off with an item of strong odor, and printers can duplicate any item – except they are all old and bad at it now.

“Nick and the Glimmung” is written in a light, simple style, but PKD starts off with a mature idea for children: The Earth government bans pets due to overcrowding, so Nick and his parents must decide how to deal with that once the existence of Nick’s cat Horace is found out. Should they obey the law, dodge the law, or emigrate to another planet?

It’s nice to see that Nick’s teacher leads a debate on this subject, and that at least some students resist the idea of capitulation. This segment slightly calls to mind pandemic-era schooling, as the teacher leads nine classes at the same time via a TV screen. Students remotely vote “yes,” “no” or “undecided.”

A quest without rules

After the family arrives on Plowman’s Planet, “Nick and the Glimmung” becomes a Tolkien-style quest, except PKD doesn’t tell us what the rules of the game are ahead of time.

But young readers should be able to relate to Nick’s constant desire to see that Horace is safe. It also helps that Horace has a colorful personality; it’s clear that PKD has affection for cats.

I think this could’ve been a cuter, funnier story. Had it gotten close to publication during Dick’s life, he or his editor might’ve wanted to take another pass to make it less stiff. Despite being simplified, the themes are probably too buried to young readers to find (except for the strong opening about the Horace issue).

Ultimately, “Nick and the Glimmung’s” biggest hook is its sheer oddity as Dick’s only children’s novel. I think PKD makes a case that his worlds and ideas – which are mostly embraced by adults whose minds work a bit differently from the norm — can translate into a learning tool for kids.

However, the book itself lacks that childlike (through an adult lens) imagination found in his better works.