John Hughes’ writing talent and knack for capturing teenagers’ voices were on display pretty early, but his direction is a little clunky at the start of his career. Granted, I gave “The Breakfast Club” a five-banana rating, but I love it despite its flaws and I suspect it was saved in the editing room.

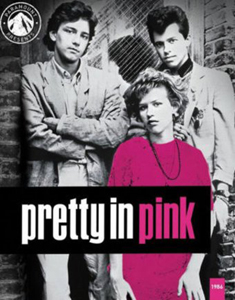

For “Pretty in Pink” (1986), Hughes remembers that high school is easier to get through with a friend, so he wisely brings in Howard Deutch to direct.

Deutch’s stellar debut

This is (amazingly) Deutch’s first movie, so he’s technically less experienced than Hughes, but he is more comfortable behind the lens. They’d later collaborate on the simple-sweet “Some Kind of Wonderful” and the silly-fun “The Great Outdoors,” but their first combined effort remains their best.

Unlike those two later films, it’s not obvious where “Pretty in Pink” is going. Even though the characters and situations are stereotypes of some kind, there are enough of them – and they bob and weave in each other’s spheres so naturally – that old scenarios have fresh impact.

Deutch brings out believable charms and flaws in everyone. This is the last of Molly Ringwald’s three Hughes films, but it’s her most robustly human performance, whether Andie is nervously eyeing her crush, Blane (Andrew McCarthy); studying with longtime bestie Duckie (Jon Cryer); getting life lessons from older friend Iona (Annie Potts); or serving as a de-facto parent to her own troubled father Jack (Harry Dean Stanton).

That last relationship is the most crucial. In “Sixteen Candles,” Ringwald’s Sam is defined by how sad it is that her family forgets her birthday; here, Andie is immediately shown to be actively loving as she encourages her dad. I don’t quite see the intrinsic Ringwaldian magic that Hughes does, but Deutch gets closer to teasing it out.

Filled with real moments

Wonderfully edited by Richard Marks, “Pretty in Pink” is filled with real moments that get that extra kick from a smile to cap a scene. Blane might be a slick preppie on the outside, but he smiles and we see he’s fragile.

Duckie might be a snazzy dresser and cool cat, but he smiles and we see he’s trying so hard to impress Andie and has constant butterflies. Iona is an edgy record-store clerk but she smiles and we see how she wistfully views bygone days through her younger friend. Jack is a lout who can’t get a job, but he smiles and we see how much he loves his daughter.

Cryer (who is outright bad one year later in “Superman IV”) has never been better, Stanton has never been more unexpectedly good (I think of him from much different roles in “Alien” and “Escape from New York”), and heck, even James Spader – despite doing his usual smarmy Spader-isms — puts a hidden layer into preppie king Steff.

Speaking of layers, all the dressings are in place in “Pretty in Pink” – including the wardrobe (Duckie and Andie remind me of a subset of alterna-cool teens that continued well into the ’90s), and settings and locations that denote rich and poor.

Stellar soundtrack

But above all, we gotta talk about the music.

It’s been said that music is the most underrated part of cinema, but it’s hard to underrate this soundtrack. Everyone talks about “Breakfast Club’s” “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” and “Ferris Bueller’s” “Oh Yeah,” and they’re not wrong to do so, but those songs dominate those whole soundtracks. “Pink’s” is stronger front to back.

Andie’s favorite club features a live band that plays the best kind of new wave music at that precise point in time when it was mainstream. So was Andrew Dice Clay, who plays the club’s doorman; his presence is not a weird juxtaposition, even though he’s not asked to be particularly funny, as this isn’t a comedy.

(“Pink” is labeled a comedy on IMDB, but it’s really a Hughesian drama; it’s a comedy only if you’re able to laugh at high school life. So I guess it becomes more of a comedy as time goes by.)

As for the non-diegetic tracks, “Pink” is bookended not by one repeated song, but by two different songs that illustrate the change in mood: The Psychedelic Furs’ title track at the start and Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark’s “If You Leave” at the end. I love this, because the film itself isn’t about circumstances changing so much as is it’s about perspectives changing.

Both of the aforementioned tracks sound a little like The Smiths, and speaking of which, “Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want” plays when Duckie is alone in his drab room, pining over Andie. Check out the set design here: Duckie’s mattress is directly on the floor and there are scribbles on the wall.

Not-so-lucky Duckie

It’s never brought up in the dialog, but Duckie is apparently even poorer (and at least equally creative at compiling a great wardrobe on the cheap) than Andie, who obsesses over her class difference compared to “richie” Blane.

I don’t know if it’s intended, but one could read it as Duckie’s life being a colorful but false performance for Andie. When no one is looking, his most interesting trait is that he’s heartsick. And great sad music aside, even that is not a cool look to an observer.

Duckie, who in a heartbreak- and hormone-fueled rage makes fun of Blane’s name even before George Carlin did, is probably the teenager Hughes most related to in his screenplay. “Pink” presents a decisive yet tender lesson in the fact that you can’t control how other people feel.

This is sometimes lazily called a “friend zone” movie, but it doesn’t present the case that guys put themselves in the “friend zone” (a reductive argument that suggests men’s presentation of themselves leads to women’s decisions, thus minimizing the fact that women have complex inner lives of their own). Instead, it simply states that Andie doesn’t see Duckie as a romantic interest and never will.

So then Duckie must decide if the friendship is worth the pain; Hughes doesn’t posit a “right” answer, but I must say I adore both Duckie’s appearance at prom (later riffed on, with a different meaning, by Angel in “Buffy’s” “The Prom”) and the fact that, from across the dance floor, he connects with another girl (future first Buffy Kristy Swanson no less!).

The latter point is wish fulfillment, and Duckie looks at the audience as if to say “Sure, it’s obvious, but it’s what you wanted, right?” You are correct, sir.

Choose your POV

Duckie is both critically and sensitively portrayed, which I appreciate. Meanwhile, I can’t speak to Andie as a portrayal of a teen girl, but judging by how “Pretty in Pink” is appreciated by women, I suspect Hughes gets her right too. And, thanks to Ringwald, I thoroughly like Andie as a person, even though she’s breaking Duckie’s heart.

It’s a neat trick of Hughes’ and Deutch’s that “Pretty in Pink” can be seen as a movie about Duckie or as a movie about Andie, depending on who the viewer relates to. (I wouldn’t be surprised if some see it as a Blane movie, for that matter.) In fact, I think it’s the neatest trick of Hughes’ career.

I admire “Breakfast Club” as a piece of guerrilla filmmaking, but I give the overall edge among Hughes’ “high school years” to “Pretty in Pink” – a film that obviously inspired Kevin Williamson’s “Dawson’s Creek” a decade down the road yet never crumbled into a stodgy, dusty old “influence.”

“Pretty” is too cheap an adjective. This is a beautiful piece of cinema in every way.