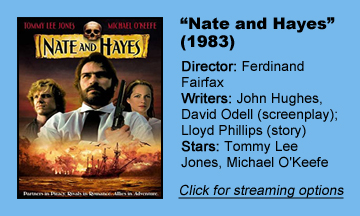

“Nate and Hayes” (1983) was probably not a passion project for John Hughes – who co-writes the screenplay with David Odell (“Supergirl”), from a story by Lloyd Phillips. It’s probably a case of him earning a paycheck as he worked to gain Hollywood clout. However, he infuses some fun and energy into this 19th century South Pacific swashbuckler.

I wouldn’t know this is a Hughes script if I had gone in blind, but considering that Odell tends to embrace magic and mysticism in his other works, I’m tempted to credit Hughes for “N&H’s” grounded nature.

Like a less campy ‘Pirates’

The main reasons “N&H” is easy to watch are the suave Tommy Lee Jones as moralistic pirate Bully Hayes, a less campy version of Johnny Depp’s Jack Sparrow from “Pirates of the Caribbean”; energetic direction by Ferdinand Fairfax; and the filming locations of Fiji and New Zealand.

The lens of Tony Imi captures largely untamed areas of the planet with their clean blue waters. The costumes reasonably bring us back to the mid-1800s, and I appreciate the detailed sailing procedures such as bringing down the sails and setting the anchor.

Despite coming first in the title, Nate can’t compete with Hayes for screen presence; Michael O’Keefe is clearly not the actor Jones is. But one scene, which feels like it’s written by Hughes, nicely illustrates their bond.

They both love Sophie (the lovely Jenny Seagrove) – initial milquetoast Nate is due to marry her, but she has eyes for adventurous Hayes too – so after a doing a bunch of drinking, they come upon the advanced idea of letting Sophie decide. I like that the title duo are friends from this point, although it’s a shame the actors don’t have much chemistry.

A simple yet messy plot

The plot manages to be messy considering how simple it is at its core. Ben Pease (a game Max Phipps), a pirate who hates Hayes’ guts ever since Hayes accidentally shot Pease’s balls off (that strikes me as a Hughesian detail), is helping Germans reach an anchorage agreement on a particularly savage island. (Even pre-Nazis, Germans make ideal go-to villains.) Pease draws the wrath of our heroes by nabbing Sophie, who has high value as a sacrifice to the savages’ gods.

As good as this film looks overall, Fairfax seems limited by the budget at times. The savage island is bizarrely cold and foggy upon Pease’s arrival, but “N&H” can’t sustain that mood. When Sophie is being lowered into (apparently) a fire pit, the log-constructed stage and lowering mechanism are grand, but we don’t get a good look at the pit.

On the other hand, we get a bustling port town in Samoa and several battle sequences packed with extras, so our window into the mid-1800s doesn’t quite crack.

A handful of little moments don’t make sense, and I was totally faked out by not recognizing the framing mechanism – and I don’t think it’s supposed to be a fake-out. Hayes is a captive of Pease early on, and he still is at the end of the high-seas adventure; so then yet another rescue is needed to wrap up the framing story.

I assume the filmmakers envisioned a multi-movie saga in the vein of “Indiana Jones,” because “Nate and Hayes” is a better series title than individual film title. (It was renamed “Savage Islands” in some markets.)

Nate, Hayes and Sophie could’ve swashbuckled through those beautiful blue seas for a few more films. That they don’t is not a big loss to cinema history, but “Nate and Hayes” is enjoyable lazy-afternoon viewing.