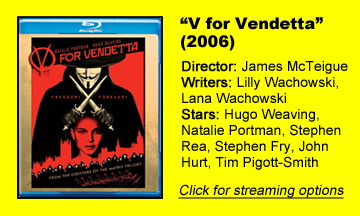

When I saw “V for Vendetta” in theaters in 2006, having gone in mostly cold, it washed over me like a new, surprising experience. Although I’d always been suspicious of authority, this movie – which often makes top 10 lists of most libertarian films – clinched it for me.

Oddly, I don’t think it’s entirely because of the messages. “V for Vendetta” is certainly a message movie about the value of freedom and the untrustworthiness of governments, but more than that, it’s such a beautifully engrossing work of art.

Hope above plausibility

Indeed, the things that happen in the film are often under-explained or Pollyanna-ish. Most of the strategic machinations and materiel acquisitions by freedom fighter (or “terrorist,” from the British government’s perspective) V (Hugo Weaving) happen off screen.

In the grand finale, Inspector Finch (Stephen Rea) believes the crowd of black-robed Guy Fawkes-mask wearers will face the fate that always befalls a group of unarmed people going up against a group of armed people. But they don’t – and we accept it and love it because “V” is consistently about hope above plausibility.

With the possible exception of “Garden State,” I think this is Natalie Portman’s finest role. Evey goes through the transformation from a scared, meek British subject to fearless revolutionary – largely because of the hard-to-watch segment where it turns out V, rather than the government, tortured and caged her.

At the end of the multi-month period, Evey is no longer scared. But also, the filmmakers emphasize Portman’s aesthetic beauty; it feels wrong that a vibrant young woman should have her head shaved and eventually be executed – we experience the wrongness and wastefulness without needing to grasp the political nuances.

V hits the bullet points

That’s not to say that “V” – via verbose V himself — doesn’t hit the bullet points of how governments grow into monstrous entities, from corporatism to media control to the surveillance state to screw-ups recast as false flags. A big one that’s left out is federal debt and monetary control, too abstract to fit here.

At the other side of the emotional spectrum, we see a lesbian being imprisoned and brutalized, which doesn’t fit with the Western style, wherein newly recognized rights to equal treatment make for ideal carrots to dangle before voters.

Hugo Weaving is great as the title character, although I’m not exactly sure how. I can barely wrap my head around the fact that this is the same actor who plays Agent Smith in the “Matrix” films (like “V,” written by the Wachowski siblings). V never takes his mask off – or is that him posing as Rookwood? – but it doesn’t hurt the performance; it might even enhance it.

Initially, the juxtaposition of the mask’s grinning appearance (actually an upturned mustache) doesn’t fit someone with the serious goal of revolution. But it fits better when we see V’s collection of banned artworks, including a jukebox of hundreds of songs. V has more joy for life than the man with the power, always-big-screened Chancellor Sutler (John Hurt, back in “1984” mode but on the other side).

A noir detective

The Wachowskis and director James McTeigue give us three characters to latch onto. If we’re not all-in with V, if we’re not quite as open to V’s ideas as Evey, we have Rea’s wonderful turn as Finch to relate to.

He’s a noir detective, putting the pursuit of the truth ahead of loyalty to the government. Finch looks burned out, but he has not moved beyond doing the right thing: We know from the beginning that Finch is the cop whose flip to the good side could be pivotal.

“V” is a story about people more than the revolution they are fighting, but the filmmakers also handle the latter part wonderfully. They include comedic parts such as variety-show host Deitrich’s (Stephen Fry) skit that makes fun of Sutler. Slices of life like this – and cuts to families watching TV and being influenced – are comedic in the moment. But somehow – and this is totally the right decision – “V” is never a satire or comedy.

Indeed, as he knew would happen, Deitrich is captured and executed after the skit airs – despite being essentially the Jay Leno of his world. Sutler flies even more off the handle later when he flat-out announces on TV that the British citizenry is the enemies of the British state.

Always timely and universal

This gets me back to the “wishful thinking” aspect of “V”; if only politicians would snap and speak so clearly and honestly in the real world, then maybe people truly would rebel. (To the fictional citizenry’s credit, they realize they are in Sutler’s crosshairs before he clearly says so, and they’ve left their couches for the streets.)

“V” is fictional and set in the near future, and in Britain because Alan Moore (who wrote the graphic novel in 1982 and declines to be credited in adaptations of his work) is British. In the film’s world, as we see in news clips, America has become a third-world country because of, well, variations on things that have happened in the real world since 9/11, only slightly more extreme.

On this Fifth of November, “V” might be mentioned more than in past years because it comes on the heels of an election featuring two unapologetic, unsubtle authoritarians. But it’s always timely, and it’s always universal. It shows oppression and revolution as a pattern that repeats, as predictable as one domino hitting the next.

But while human history is littered with repetitive violence, we can also produce artistic beauty, and “V for Vendetta” is a standout example.