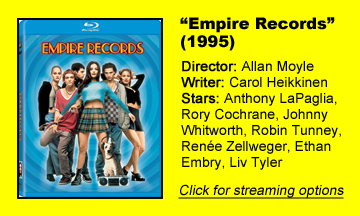

“Empire Records” (1995) is perhaps not technically or objectively a good movie, but it’s almost impossible to dislike it. Choppily yet insightfully written by Carol Heikkinen, with game-saving direction by Allan Moyle and energetic editing by Michael Chandler, the film started as an underdog to its own soundtrack, highlighted by “Sugarhigh” and “Til I Hear It from You” and owned by every CD-collecting teen of the time.

As time goes by, those of us who used to apologize for liking this movie seem to have been vindicated, as “Empire Records” has become a cult classic.

Energetic cast overcomes shaky plot

Watching it with a critical eye, this can partly be justified and partly not. The film has its share of lazy writing, including the notion that $9,000 marks the difference between manager Joe (Anthony LaPaglia) buying Empire Records from the current owner versus the current owner selling it to impersonal national chain Music Town. (Yes, the store names are backward from what they should be.)

Nine grand is nothing to sneeze at, of course, but it’s too small an amount to be pivotal in a corporate takeover.

Yet the film’s energy – as supplied by a talented young cast that’s happy to be there – allows us to not dwell on the shaky plotting. The film should be enjoyed as a day in the life of the store (albeit a big one, since it’s Rex Manning Day), with the plot serving as a mere foundation.

It’s stating the obvious that the female leads are at the height of their hotness: Liv Tyler as Corey, in the skirt-and-sweater ensemble made iconic by the CD cover; Renee Zellweger as Gina, who illustrates the inconsistency of the Music Town dress code by wearing only an apron; and Robin Tunney as Debra, who borrows the shaved-head look of Sinead O’Connor and Ellen Ripley.

But it shouldn’t be overlooked that all three actresses elevate their relatively thin arcs, as their characters deal with amphetamines, inappropriate Rex Manning crushes, suicidal tendencies, and their up-and-down friendships. (Shaming of the promiscuous Gina dates the film, but the rivalries amid the girls’ friendships are timeless.)

Among the guys, there’s an unrecognizable-from-“Dutch” Ethan Embry as Mark, a manic, skinny answer to Jack Black; Johnny Whitworth as introspective A.J., whose pining after Corey is painfully relatable; and Brendan Sexton as shoplifter Warren, who deep down wants a job at the store. Watching it now, many of us would risk time travel to work at Empire Records in 1995.

Music industry at crossroads

Again stating the obvious: “Empire” is at the crossroads between the early Nineties (which was like the Eighties) and the late Nineties. “Empire” takes a step toward the next zeitgeist, though. Lucas (Rory Cochrane) wants to save Empire Records not just for himself, but for his fellow employees and for their customers.

Granted, Empire Records successfully peddles CDs, tapes and vinyl, but everyone sees the corporate takeover coming, and the mismanagement that entails. No one senses the end of physical media yet, but that makes the movie poignant when viewed today.

“Empire Records” is generally comfortable defining kids as individuals with problems outside the store, yet it doesn’t emphasize blame on parental upbringings the way an Eighties film might. Granted, mother issues are referenced – Gina doesn’t want to be like her mom, and Debra doesn’t know where hers is – but we don’t meet any parents.

Empire Records, especially its employee area in the back, is clearly the teens’ place. (The 2018 period piece “mid90s” recognized this social aspect of the time, featuring a skateboard store that doubles as a teen hangout.)

That said, there’s nothing strange about Joe being both the manager and one of the gang, a balancing act LaPaglia is up for. Plus, we later learn that Joe is almost a surrogate father to Lucas, something that adds a layer to Lucas’s loss of a day’s gross (gambling it away, trying to save the store) and explains why Joe doesn’t fire him. (I admit Joe beating up Lucas in his office is tonally strange.)

Influence on later music movies

Meanwhile, there are hints of “High Fidelity” (2000). The employees draw M&Ms to see who gets to choose the store’s music at the start of the shift. They dance to the music even during business hours.

They don’t talk about music in as much detail as the Championship Vinyl gang, but it is interesting to follow the arc of their views of Rex Manning (Maxwell Caulfield): They like him inasmuch as he’s a musician doing a signing at the store, thus making for an eventful day. But once they get to know him, they feel more comfortable judging his music (as bad).

Heikkinen also adds cynicism in the vein of “Josie and the Pussycats” (2001). The obvious parallel is the notion of something “genuine” in music being transplanted by something “corporate” – the band in “Josie” and the store in “Empire.” Additionally, the Manning song “Say No More (Mon Amour)” is a joke on par with DuJour’s “Backdoor Lover” – something that’s real within the movie’s world but a parody of similar songs in the real world.

“Empire Records” might be messy in regard to having a tight focus or a logical conflict, but its meandering is purposeful and rather charming, and in the end most of the characters are served. Still, the year and the store are the biggest stars, and that’s why the movie is becoming more appreciated.

“Empire Records” encapsulates this point in music fandom and the way we socialized.