We all go a little mad sometimes, so from Nov. 27-Dec. 11 we’re dragging the swamp behind the Bates Motel for insight into the films of the “Psycho” franchise. Wrapping it up is “Psycho” (1998):

A rare shot-for-shot remake

As nerdy film fans, we often wonder who to credit or blame for the success or failure of a movie: the writer, the director, the actors? But in contrast to theater, which thrives on remakes of sometimes centuries-old scripts, few screenplays are made twice.

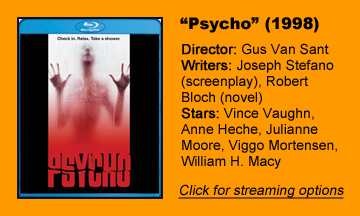

Director Gus Van Sant, enjoying some cachet in the wake of 1997’s “Good Will Hunting,” gives us a rare major example of a nearly shot-for-shot remake: writer Joseph Stefano’s “Psycho” (1998, remade from director Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 classic).

The differences sometimes illuminate what makes “Psycho” ’60 so good. The big change is that “Psycho” ’98 features a weaker handoff from Marion Crane to Norman Bates as the focal character.

Anne Heche is magnetic as the lithely sexy and subtly sly Marion, who steals $400,000 from her workplace. The new movie is in color, not black-and-white, and Marion is now literally colorful. It adds up to a huge contrast from Janet Leigh, whose Marion is equally compelling, but in a much less flashy way.

Vaughn fumbles the handoff

The 6-foot-5 Vince Vaughn plays Norman as an overgrown child who bounds up and down the steps between the hotel and house. This characterization is confirmed when Lila (Julianne Moore) enters Norman’s room amid her search for Norman’s mom (voiced by Rose Marie) and finds that it looks like a child’s room.

Vaughn’s Norman is eager to please, like a kid, but Anthony Perkins’ portrayal has us more on the edge of our seat because we can’t guess what he’s going to do. As such, the 1960 version gets better upon the Marion-to-Norman handoff, whereas the 1998 version gets weaker. It’s a subtle difference, but enough to color viewers’ feelings toward the two versions.

Viggo Mortensen interprets Marion’s boyfriend Sam for the times. He resolves the old-fashionedness of Stefano’s screenplay by making Sam a Southern-accented throwback – and also an overt womanizer. Sam’s behavior probably wouldn’t fly in the #MeToo era, but in 1998 the impression was simply that he is more brazen than 1960 Sam.

It’s fairly clear that John Gavin’s Sam loves Marion. With Mortensen’s turn, Sam may love Marion, but he’s happy to move on to her sister Lila with disturbing quickness when he learns of Marion’s disappearance. He kisses Lila on the cheek before going off to investigate the motel, a moment that intentionally or not mirrors Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel, wherein Sam mistakes Lila for Marion and kisses her.

Moore follows Heche’s lead and makes Lila into a more modern, less reserved woman. Her Walkman and headphones make her an individualist, and she demands answers from the Fairvale sheriff (Philip Baker Hall, taking over for John McIntire). Vera Miles’ Lila has a serious, laser-focused presence, but she’s more genuinely apologetic after raising her voice to the authority figure.

Bizarre artistic touches

As much as I defend “Psycho” ’98 as a worthy artistic endeavor, it gets artsy-fartsy in two places: When Marion is dying, quick shots of thunderstorms are interspersed. And when Arbogast (William H. Macy) falls down the stairs, a couple of random images are intercut. I think the idea is to illustrate what a dying person might see in their final moments: quick visions that don’t have as much meaning as we might hope.

But the insertions make it seem like the remake is trying too hard, and this is a shame because in its opening scene “Psycho” ’98 suggests it could be a brilliant exercise in changing tones without changing the script.

After their lunch-break tryst in a Phoenix hotel room, Marion takes her leave and says Sam can’t follow because he doesn’t have his shoes on. In “Psycho” ’60 it’s a literal line because Gavin’s Sam is dressed except for his shoes; in “Psycho” ’98 it’s a cheeky (pun intended) line because Mortensen’s Sam is naked. Unfortunately, there isn’t another scene that comes off so clever.

A tighter edit

Even though Van Sant’s version subtracts only one scene from Hitchcock’s version (Lila and Sam talking to the sheriff after church) and adds the aforementioned moments, it’s 4 minutes shorter. When one considers that “Psycho” ’60 has no closing credits and “Psycho” ’98 has robust credits, the new version’s comparative brevity is even more pronounced.

This is partly due to tighter editing by Amy E. Duddleston, who shows sympathy for modern attention spans. And it’s partly because actors talk and move through scenes faster in 1998; life has sped up, and so have fictional portrayals of life.

Vaughn is jittery whereas Perkins is socially awkward, and the closing monolog by Dr. Fred Richman/Dr. Simon is notably tighter. Robert Forster gives a more professional psychiatric rundown of Norman compared to Simon Oakland’s turn. The 1960 monolog holds the viewer’s hand whereas the 1998 version thinks the audience is savvier; as such, the speech takes on a creepy rather than explanatory vibe.

Usually experimental films get generous treatment from critics, but “Psycho” ’98 is a notable exception; the same goes for the fan response – it rates 4.6 on IMDB compared to 8.5 for “Psycho” ’60. Certainly, the new version is not as good as the original, yet it’s not amateurish and it by no means squanders Stefano’s material.

A lot of the explanation for the rating gap is the public’s hatred of the very idea of a second crack at the same screenplay, a fate also suffered by “The Lion King” (2019). But I think it’s fun to compare the two versions and gain an intellectual appreciation for how and why Hitchcock did it better.

Schedule of “Psycho” reviews:

Friday, Nov. 27: “Psycho” (1960)

Wednesday, Dec. 2: “Psycho II” (1983)

Friday, Dec. 4: “Psycho III” (1986)

Wednesday, Dec. 9: “Psycho IV: The Beginning” (1990)

Friday, Dec. 11: “Psycho” (1998)