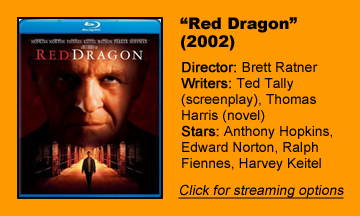

To mark the 40th anniversary of author Thomas Harris’ invention of Hannibal Lecter and the 30th anniversary of “The Silence of the Lambs” – the only horror film to win Best Picture – we’re looking back at the four books and five films of the Hannibal Lecter series over nine Frightening Fridays. Next up is the fourth film, “Red Dragon” (2002):

Back to the beginning

After the commercial success of “The Silence of the Lambs” and “Hannibal,” there were no more of Harris’ novels to adapt for further box-office dough, but the producers found a way around that: remaking “Manhunter” to match up better with the other films, namely by using Anthony Hopkins as Hannibal Lecter.

Even if the impetus is commercial, “Red Dragon” is obviously the better film, mainly because the adaptation by writer Ted Tally – returning from “Silence” — brings out elements of the novel skimmed over by “Manhunter.”

After defending the existence of “Psycho” (1998), I’d be a hypocrite to rip “Red Dragon,” but watching it close on the heels of “Manhunter,” it loses something by being (inevitably) redundant.

A slicker style

And I like the original’s style more: Eighties touchstones (which were perhaps effortless on Michael Mann’s part, as it was made in 1986), and amateurish and cheap touches that add to the aesthetic.

Director Brett Ratner’s “Red Dragon” is in the slick, money-is-no-object blockbuster style of the prior two Hopkins films. It’s set in the 1980s, as indicated by its place on the timeline, plus the state of home-video technology, plus the date on the bottom of the screen.

Will Graham’s (Edward Norton) promise to Lecter of access to the AMA computer database is the only perhaps-apocryphal element I noticed. But it feels like it’s set in 2002.

Another great screenplay

Tally is this movie’s all-star, giving us more of Lecter than the book does without forcing anything, and adding layers to Will and especially Francis Dolarhyde (Voldemort actor Ralph Fiennes, trading a noseless face for one with a cleft lip).

In the cold open, Lecter is irked by a bad flautist and serves his thymus as sweetbreads to his unknowing orchestra colleagues; this incident is mentioned by Harris but not written as a scene in any of the novels.

Tally provides a front bookend for Hopkins’ trilogy, which has surprisingly little cannibalism in it, but now starts and ends with cannibalism, along with Lecter’s reluctant but fierce physical attacks on his two charges (Graham here, Clarice Starling at the end of “Hannibal”).

Tally does Harris one better with the ending to “Red Dragon.” He preserves the “one last scare” (which “Manhunter” skips) but beefs up the showdown as Graham uses his psych knowledge about Dolarhyde in order to defeat him.

Hopkins returns, Norton steps in

Hopkins (who, sure, is better than Brian Cox, but he gets more to chew on – pun intended) is joined among “Silence” veterans by Anthony Heald’s Dr. Chilton and Frankie Faison’s Barney.

But the film couldn’t get Scott Glenn back as the FBI’s Jack Crawford, and instead of casting a younger actor who looks like Glenn, they cast an older actor who doesn’t look like him (Harvey Keitel). Keitel is fine, but I was thinking “Is this film trying to match up the continuity, or not?”

Norton equals and maybe surpasses William Petersen’s performance, portraying Will as a soft-spoken, good-hearted guy who just happens to understand the thought process of serial killers; Hugh Dancy would later take the baton in the “Hannibal” TV series. Will’s family life in Florida with wife Molly (Mary Louise-Parker) and their son Josh (Tyler Patrick Jones) is sparsely but nicely shown.

It’s fun to get a dose of Philip Seymour Hoffman as tabloid reporter Freddy Lounds. The biggest casting improvements, though, are Fiennes and Emily Watson as Francis’ blind girlfriend Reba. They have chemistry, and Watson conveys that Reba is not along for the ride in this relationship.

A Fiennes villain

From talks with her colleagues, Reba has reason to believe that Dolarhyde is both physically attractive (he’s in great shape and his facial deformity is minor) and his social awkwardness likely comes from shyness; he might be a legitimate catch.

Fiennes gets a chance to play up the decent side of Dolarhyde that was ignored in “Manhunter.” We see in mental flashbacks that he was psychologically abused as a child, and even as an adult, he’s fighting an inner battle with the Red Dragon over the fate of his girlfriend.

Although Norton is fine in the procedural stuff, his best acting comes at the end — when Graham comforts Reba, when he looks through Dolarhyde’s scrapbook, and when he is forced into that final confrontation.

If there was a way to combine the style of “Manhunter” with everything else from “Red Dragon” – perhaps pasting the synth score over the top – a masterpiece could result. The second attempt is superior enough to justify its existence, but watching them back-to-back certainly kills the suspense. If you watch only one version, do what the producers intend: Watch “Red Dragon.”