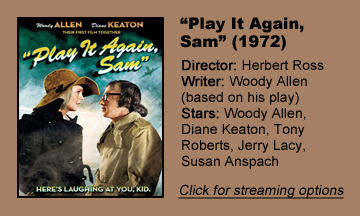

Because of its Oscar and place at the top of many “Best of Woody Allen” lists, 1977’s “Annie Hall” is often seen as an entry point into Allen’s catalog. But a case could be made for “Play It Again, Sam” (1972) as an earlier film where Allen puts it all together – not abandoning his trademark brand of comedy, but focusing more on crafting a character, a core relationship and a distinct hook.

While I think “Annie Hall” is the slightly better picture, I also adore “Play It Again, Sam.” It perhaps gets slightly less attention because it’s not directed by Allen, but rather by Herbert Ross, who wonderfully gives scope to what originated as a stage play by Allen.

Love for cinema

The framing device especially brings out cinema’s magic: The opening shot finds Allan (Allen) mesmerized by his beloved “Casablanca”; the closing scene pays homage to that Humphrey Bogart classic.

The set designers overdress film critic Allan’s apartment with movie posters, but to good affect: He’s a man whose comfort with film and music is unquestioned but who is helpless around women (he’s been successful with one, Susan Anspach’s Nancy, but she has divorced him) despite the fact that women are all he thinks about.

A standout supporting turn comes from Jerry Lacy as Bogart, who is metaphorically on Allan’s shoulder (sometimes leaning toward angel status, sometimes devil) and literally in the background of frames, speaking as Allan’s subconscious.

When Allen met Keaton

But “Play It Again, Sam” (named after a misquoted line from “Casablanca”) is rightly most known as the first collaboration between Allen and Diane Keaton, who – as Linda – believably plays a woman who loves this unmanly man for his sweet nature. Plus Linda and Allan have the commonality of both being neurotic.

But Linda is married to Dick (Tony Roberts, on point as a traditional go-getter leading man who is focused on his real-estate dealings).

In a simpler rom-com, Dick would be a jerk and Linda and Allan would stumble through 90 minutes before realizing they are perfect for each other. But “Sam” has a more realistic sensibility: Dick is not a bad guy, Linda loves him (even if she also loves Allan), and Allan doesn’t want to hurt Dick, his best friend.

Laughs from absurdities

“Sam” also plays as a comedy, though, and even gets laughs from absurdities – although it certainly isn’t a farce like “Bananas” or a genre parody like “Love and Death.” It pushes furthest into ridiculousness when Allan approaches a cute young woman (Diana Davila) at an art gallery.

Like a stereotype of a sexy, morose Frenchwoman, she espouses on the depths of despair she sees in a Jackson Pollock painting, and we can see Allan thinks she’s perfect for him. Allen can’t resist putting this exchange in the screenplay:

Allan: What are you doing Saturday night?

Museum Girl: Committing suicide.

Allan: What about Friday night?

That’s arguably too much for a realistic film, but it’s funny enough that I forgive it. For the most part, “Sam” is grounded, while still being laugh-worthy. In a masterfully staged sequence, we spend a good amount of time watching Allan getting ready for a double date that will include Dick and Linda along with Sharon (Jennifer Salt).

Allan imagines things going supremely well with Sharon, but then when she is introduced to him in reality, he lets out a caveman-like grunt. While “Sam” is sometimes over-reliant on pratfalls, the ensuing scene where Allan bungles around his apartment trying to act cool is outstanding, building on the audience goodwill from that hilarious grunt.

Stumbling toward maturity

“Sam” has something to say about maturity, as we watch Allan growing beyond movie obsession to become well-rounded – benefiting from that very nerdery. (He’s not a pop-culture obsessive at the level of Rob Gordon in “High Fidelity,” but 1972 was way before geek culture was remotely a thing.)

How Allan relates to Bogart both stunts him and propels him forward until he doesn’t need his inner-monolog Bogey anymore.

This is a love-triangle rom-com, and it only has three main characters, yet it avoids every cliché and I didn’t know precisely where it was going. If it’s possible for someone to make a masterpiece while still in the process of finding their voice, Allen (with a nod to director Ross) does it with the delightful “Play It Again, Sam.”