Woody Allen has written many films with substantial female characters, but “Alice” (1990) is one of the few where the woman is the title and focal character. It’s not at the level of “Annie Hall” or “Blue Jasmine.” But it’s still an enjoyably transporting film – and one of the writer-director’s best-looking outings — although Mia Farrow is a soft, mild presence at its heart.

Dr. Yang’s wisdom

Farrow’s Alice sometimes comes close to spouting the neurotic dialog we’d expect from a male Allen Character (of which this film has none). But mostly she’s the description from the synopsis: She married into riches — via husband Doug (William Hurt), a New York financier/investor type – and has drifted from her values.

In one notable scene, neither director nor actress can pull off the humor of a naturally mousy woman – under the spell of Chinese herbs — aggressively flirting with a fellow school parent Joe (Joe Mantegna, “House of Games”).

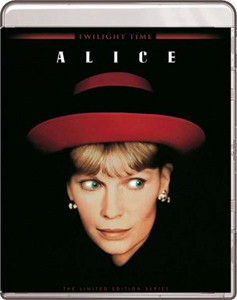

“Alice” (1990)

Director: Woody Allen

Writer: Woody Allen

Stars: Mia Farrow, Joe Mantegna, William Hurt

Still, Farrow is a comfortable core presence, and many of her co-stars are great. Particularly finding a humorous vibe is Keye Luke as Dr. Yang. He refers to himself and his patients in the third person and speaks gruffly but wisely as he distributes herbs. He’s as unique as Yoda, who might’ve entered Allen’s mind when writing Yang’s lines.

Allen has fun with the magical herbs. Alice turns invisible and eventually brings Joe into the secret. Among Joe’s first ventures is following a model into a dressing room.

Another herb causes the taker to fall in love with Alice, leading to an amusing party sequence where the men increasingly throw themselves at her. I wonder if the “Buffy” episode “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” was influenced by this.

Not going for big laughs

But “Alice’s” lesson about love is ultimately sober, as outlined by Dr. Yang:

“Love … Love is a most complex emotion. Human beings unpredictable. No logic to emotions. Without logic, there is no rational thought. Without rational thought, there can be much romance, but much suffering.”

The party sequence might be laugh-out-loud funny in a different film, but “Alice” is so mild and understated I subconsciously didn’t think I was allowed to laugh.

But it succeeds as a portrait of a wife swept into the upper class, kept so busy with tasks (shopping, exercising with her personal trainer, getting her hair done) that she doesn’t have time to reflect on her 16 years of marriage.

The film isn’t harshly anti-rich, but some viewers will take for granted that Alice’s life is empty because riches have replaced matters of substance. We see flashbacks to young Catholic girl Alice (Rachel Miner, “Bully”), wanting to become a nun. Her sister (Blythe Danner) steps in to affirm that Alice has changed.

di Palma finds beauty

On the other hand, “Alice” is gorgeous thanks to the location scouts and set designers and the lens of Carlo di Palma. He joined Allen for 1986’s “Hannah and Her Sisters” and would team with him throughout the 1990s. This is among my favorite Allen/di Palma pictures to look at; I could enjoy it on mute.

At least half the shots open on a striking location. Even if it’s Alice’s fifth trip to Yang’s office, di Palma shows it to us from an angle that makes it new. Or rather: old. It’s a thoroughly lived-in space above a Chinese restaurant. Boxes are piled in corners, patients peacefully sleep on couches and mats.

Places like this, and Alice’s now-rundown childhood home, are old and earthy.

Meanwhile, Alice and Doug’s lavish apartment, Doug’s office and even studio musician Joe’s stomping grounds are delicious time capsules of 1990 high society. Joe’s ex-wife works in advertising and has a wall of connected TV screens. Couches are of fine leather.

Joe’s bedroom is a penthouse with slanting windows looking across the city; the film makes it even more striking with rain in a key scene.

A heartfelt contradiction

“Alice” criticizes excess but di Palma and company make these places appealing. This contradiction is at the heart of many Allen films. His characters are often decently well-off yet haunted by internal problems.

Here, Allen goes meta and comments on his own writing. In Alice’s writing class, the teacher says a script (to be portrayed by actors) leans external, while a story (something to be read only) tends to be internal.

As noted, Alice does not pop off the screen. Partly that’s because of Farrow’s range and demeanor, but it might also be because Allen is forcing a naturally literary piece into a performed piece. Then again, with di Palma’s skills, I can’t possibly wish “Alice” were in a non-visual medium.