I both thoroughly admire and hate watching films about wrongly accused people, so I entered “The Wrong Man” (1956) with some dread. But I can’t deny its artistry, impact and importance as, without being preachy, it illustrates the “meat grinder” (to quote Henry Fonda’s Manny Balestrero himself) that the justice system can be to anyone, especially an innocent man.

In Alfred Hitchcock’s only movie directly based on a true story, Fonda plays the ultimate Everyman — almost a milquetoast, but someone with tremendous inner strength. He loves his wife and raises his two young boys in a homey, 1950s sitcom style. If it was remade and dramatic license was taken, we might see an overt mental-health impact on Manny.

Always subtle in its messaging, “The Wrong Man” gives a sense that Manny’s ordeal under the New York City police’s persecution would be much worse if he didn’t project as a kind, calm man while being taken in, arrested, charged, jailed and tried.

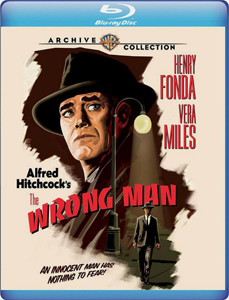

“The Wrong Man” (1956)

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Writers: Maxwell Anderson, Angus MacPhail

Stars: Henry Fonda, Vera Miles, Anthony Quayle

Instead, the mental-health breakdown goes to Manny’s wife, Rose (a masterfully understated Vera Miles). It’s powerful, though, that this happens away from the eyes of the authorities who caused it. When Manny confronts the actual hold-up man in the final act, he says “Do you know what you’ve done to my wife?” But, maybe because of my own interest in police misconduct, I see the authorities as the central wrongdoers in “The Wrong Man.”

Hairline cracks in the procedure

Interestingly, Hitchcock (working from a screenplay co-written by Maxwell Anderson and based on Anderson’s book about the real events) presents the investigation in procedural fashion. This is much the same as in “I Confess,” wherein one could argue the accused priest brings the weight upon himself by keeping his mouth shut. Indeed, although many Hitch films are about wrongfully accused people, he rarely presents the police as total buffoons.

One key mistake sends “The Wrong Man’s” police down the wrong path. An insurance company clerk believes Manny is the holdup man from a few months earlier. Hitch shows how her belief influences the belief of two coworkers. Then additional witnesses are influenced simply by the police asking them to look at this man. It’s a variation on the “presumed guilt” phenomenon: For example, we read a newspaper report of someone’s arrest and charges and assume they are most likely guilty.

Later, we see that the actual criminal does look remarkably like Manny. But that still raises the question of whether we want a justice system wherein mistaken identity is a real – however slim – possibility. Combined with bad luck in proving alibis, and innocent people can lose their liberty even without overt police corruption.

While it’s remarkable that this case went to trial without any forensic evidence and relying on one mistaken eyewitness, we know it did. Hitchcock introduces the film as being based on a true story. (Interestingly, and unfortunately, the “based on fictional events” boilerplate wording follows in the opening credits. However, this isn’t a “Fargo” type of “true story.” The real Balestrero did go through this. The “fictional events” words are mandated because it’s a dramatized telling of those events.)

More than merely homework

I didn’t learn anything new from “The Wrong Man” about how it only takes some bad luck for someone to become among the 4 percent of imprisoned innocent people in America (the actual number is higher, because some of the remaining 96 percent are likely innocent but unable to prove it).

But I admire the telling of the story and its blend of procedural, factual scenes along with the mental-health price on people who go through this. One minor slip-up comes at the end, when (in what seems like a studio mandate), we get a “happily ever after” crawl.

In the real world, Rose remained traumatized by these events. I desire a happy ending as much as the next person, but I think truthfulness is important in a true-story film. It might’ve been powerful to include Rose’s actual status in the closing crawl, perhaps along with a note about the lack of consequences for the police. Balestrero received a mere $7,000 in damages from the city, and that of course comes from taxpayers, not the individuals who screwed up.

“The Wrong Man” isn’t pleasant to watch, but it is an engrossing – and slightly lighter — precursor to other important “wrong man” films ranging from docudramas (“The Hurricane”) to works of fiction (“The Shawshank Redemption”). It’s a sober, unfunny experience, but so well crafted that you do experience satisfaction on a level beyond the mere completion of history homework.

RFMC’s Alfred Hitchcock series reviews works by the Master of Suspense, plus remakes and source material. Click here to visit our Hitchcock Zone.