Among my rewatches of early Aughts films I count among my all-time favorites, I was most trepidatious about “Garden State” (2004). A friend of mine used to love it as much as I do, but now dislikes it. It’s been criticized in the two decades since its release for being one of those films where the guy (Zach Braff’s Andrew) leans on the girl (Natalie Portman’s Sam) as his savior. The argument goes that male viewers will unhealthily seek women of this type – a variation on the argument that violent video games make people violent.

And Sam says “retarded” an extraordinary number of times in her first scene, reminding us that the Nineties (as a cultural period) extended quite a ways into the 2000s.

A grounded yet dreamy movie

Viewed today, I (sigh of relief) still love “Garden State” as a beautiful meditation on grief, the generational cycle of depression, hope and being alive — and am impressed by how its rebuttal to the primary criticism is right there on screen. If Sam exists only for the sake of the movie, then waits in the wings for the next time the movie needs her – then so be it. Because the same applies to every character in this pleasant daydream of a film about a young man who – able to feel something for the first time – decides it’s OK to feel love.

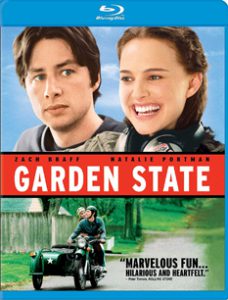

“Garden State” (2004)

Director: Zach Braff

Writer: Zach Braff

Stars: Zach Braff, Natalie Portman, Peter Sarsgaard

We see the comparative malaise of the supporting cast in a smart closing montage from editor Myron Kerstein, wherein we break from Andrew’s POV only to find everyone is doing exactly what we’ve seen them doing all along: Mark (Peter Sarsgaard) smoking a bong, Jesse (Armando Riesco) floating in his pool, and Andrew’s dad (Ian Holm) pacing and overthinking.

The film is given ethereal credence by Braff’s soundtrack selections. While it’s weird for a writer-director-actor to be most famous for his music taste, it’s totally earned in Braff’s case. If Sam is burying herself in headphones playing The Shins when she’s not actively falling in love with Andrew, that seems correct for this cinematic world.

Another coming-of-age film from the era, “Ghost World” (2001), doesn’t name its location, thus creating an ephemeral reality. “Garden State” of course names its location in the title and is shot entirely in New Jersey, the home state of Andrew – and Braff. But it achieves a similar otherworldliness.

Though it’s sometimes seen as a joke that Jersey is known as the Garden State, cinematographer Lawrence Sher makes you believe it. Gorgeous shots include a steamy swimming pool as Andrew and Sam party with Andrew’s old friends, and the trio screaming into an earthen crevice amid a rainstorm. In a film where it’s not coincidental that Andrew’s depressed mom died via drowning in a bathtub, this could almost be the Rainforest State.

Andrew is kinda quirky himself

Andrew returns home and – after the requisite numbness of his mom’s funeral and its social trappings — fires up his grandpa’s sidecar motorcycle and putters about. Andrew has so much competition for odd traits, though, that we see him as the film’s straight man. Mark makes money as a low-level wheeler-dealer, silent Velcro inventor Jesse shoots flaming arrows into the sky in his mansion’s back yard, and Sam is an epileptic former figure skater who compulsively drops white lies and looks forward to a good cry.

Quirkiness could overtake a less sure-handed movie, but Andrew’s 20-something malaise takes on a poignant weight. “Garden State” should not play so efficiently, as it gives Andrew a rather clunky, pointed backstory: His dad – well-meaning but not smartly — put him on meds after 9-year-old Andrew’s light push of his mom led to a freak household accident that paralyzed her.

“Garden State” centers on two thematic threads that can be misinterpreted if you only read a synopsis. First, Andrew is on a ton of anti-anxiety/depression drugs, but – as is apparent from his visit to a doctor (Ron Leibman) – it’s questionable whether this is proper.

He’s been on them since he was a child so it’s understandable that he can’t tell if they improve his life or make it worse. Andrew’s later acknowledgement to Sam that he needs therapy (and not of the cinematic perfect-girlfriend kind) further underlines that “Garden State” is not an anti-clinical help movie; it’s an anti-overmedication movie in the same way as the “Simpsons” episode where Bart is prescribed Focusin.

It never makes a universal statement about the value of prescription drugs; the narrative is always laser-focused on Andrew’s rather bizarre individual situation. Indeed, the film is drug-positive or drug-neutral. We get the requisite scene of Andrew and his friends doing hard drugs, and no one suffers any repercussions (although one could argue drug use slows Mark’s advancement into maturity to a crawl).

Complex vs. simple lives

The second controversial point is openly negotiated through much of the dialog between Sam and Andrew, especially as the plot becomes a sort of stream-of-consciousness journey toward the conclusion, when Mark leads them on a sort of scavenger hunt. Today, “Garden State” plays like a preemptive defense against its critics, slathering character traits on Sam and always having Andrew admire her as a full person, not just a cute curiosity.

Sam’s simplicity is often mistaken for underdevelopment. Andrew had been overwhelmed in L.A. He got one great TV movie gig as a mentally challenged quarterback but is mostly scraping by at his waiter gig and living in a first-timer apartment where the mattress on the floor is the extent of the furniture. In his hometown, the slightly younger and less life-experienced Sam leads a simpler and more genuine life.

Andrew has problems, Sam has problems, and they are both aware of it and fairly adult in their acknowledgement of it. In the conclusive airport scene, Andrew wants to go away from her for a while to work on his psychological issues – the traditionally mature choice – but she believes they should be a couple while they each work on themselves.

Love conquers … some

Some critics of “Garden State” believe this minimizes Sam, but it sure is hard to understand that perspective when watching the film. Sam has the story’s final word; it’s just that her final word is an uncool, outdated, cliched position: She chooses love. Writer-director Braff finally does achieve a sense of time and place at this moment, and – while 2004 New Jersey doesn’t totally disappear – that time and place is 1940s Hollywood.

Amid the various other meditations and mini-threads – capped by Mark’s hunt that takes them to the mysterious rock quarry — “Garden State” sneaks in its love story. Sure, the movie is in the romance genre from the moment Sam appears scrunched into a chair in the doctors’ waiting room. But it never hits us over the head with the fact that it’s a love story, because Sam and Andrew so organically like each other.

Braff tells the story from Andrew’s (his own/the male) perspective, and some segment of viewership will always rip him for not telling it from Sam’s – in which he’d be the troubled dream guy the simple, sweet girl falls for. If there was anything to forgive, I’d forgive him. If I’m screaming that into an abyss in a more critical world than 2004’s, so be it. Even beyond Sam and Andrew, there are infinite things to love about “Garden State.”