A fun thing about being a movie fan is that I still come across classics I hadn’t seen before, or – in the case of “Ghostwatch” (1992) – didn’t even know existed. Given new buzz in the wake of “Late Night with the Devil,” which follows the same premise of a ghost hunt on live TV, “Ghostwatch” sits between “Cannibal Holocaust” (1980) and “The Blair Witch Project” (1999) in “found footage” horror history. And particularly found footage films that many people thought were real (this aspect is somewhat overhyped in the case of “Blair Witch”).

“Ghostwatch’s” more cultish status results from it being a TV movie on the BBC that aired only once, on Halloween 1992. It wasn’t released on home video until 2002, so technically that should be the cited release date here, since I consider the release date to be when an average Joe has a fair chance to see it.

“Ghostwatch” is slightly above average as found footage horror, but if I was rating it based on influence and the way it provides a window into society, its rating would be five stars.

“Ghostwatch” (1992)

Director: Lesley Manning

Writer: Stephen Volk

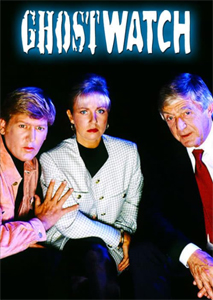

Stars: Michael Parkinson, Sarah Greene, Mike Smith

Best acting comes from non-actors

As live TV reporters, crewmen and guest experts investigate a haunted house with permission of the mother and two daughters living there, we see how writer Stephen Volk and director Lesley Manning ingeniously pave the way for “Blair Witch” and the 2017 miniseries “The Haunting of Hill House.” In the former case, people fall under the sway of a supernatural entity in the course of documenting it; in the latter case, the entity appears in the background of scenes without the characters being aware of it.

Although the film’s existence has a Halloween prankish atmosphere, the movie itself isn’t particularly cheeky, even when we learn the ghost is called “Pipes” because the mom initially told the young girls that the banging sounds were caused by the house’s plumbing. The only time I chuckled out loud was upon learning the cupboard under the stairs is called “the glory hole,” a term that gained a ribald definition after 1992.

The best performances, interestingly, come from the non-actors: Real BBC journalists Michael Parkinson, in the studio, and Sarah Greene, in the house. “Red Dwarf” actor Craig Charles fares OK because he’s playing “himself,” doing on-the-street interviews.

The worst performances come from the professional actors, who had never done this genre of performing (because, by and large, it didn’t exist). They are stiff and actorly. The voice performer who reveals over the phone the horrific origin story of Pipes is blatantly overdramatic.

But it must be said that the outspoken majority of viewers either believed this was a real TV broadcast, or they knew it was fiction (it was heavily advertised as such, and features opening and closing credits like any movie) but still found it in poor taste to present the story in a naturalistic fashion. Even with imperfect acting and plenty of edits that cue today’s savvier viewers to the fictional nature, “Ghostwatch” was unquestionably effective in its dramatic aims in 1992.

A time capsule of UK cultural values

While it’s clear that Manning and Volk vastly underestimated the credulity and intellectual laziness of the British public (for particularly harrowing viewing, watch the “Bite Back” segments on YouTube when going down your post-movie rabbit hole), UK culture of the time must be taken into context. The BBC is taxpayer funded. Like American networks, it aims for the lowest common denominator, but it is not answerable to ratings, it is answerable directly to its customers’ tastes and moral views.

Setting quality aside, the vocal majority found “Ghostwatch” to be in poor taste either because of the “live TV investigation” conceit that could fool people, or simply because it was scary – and therefore inappropriate for a wide audience. Parents trusted the BBC to responsibly co-parent with them; even after the “watershed” hour of 9 p.m., people believed nothing traumatic should be aired, in case a kid should happen to see it.

I had known that British culture is censorial toward violence and scares the way American culture is toward sex, from my time as a fan of “Buffy” when I learned about how UK viewers couldn’t see the fight scenes until the DVD releases. Diving down the “Ghostwatch” rabbit hole, I now grasp how the public TV-taxpayer feedback loop defined mainstream morals in 20th century Britain.

Thanks to streaming, matters have loosened up since then. “Ghostwatch” could only exist, both as a film and as a phenomenon, at the precise time of its release. The internet emerged a few years later, and the large minority of people who loved the film came out of the woodwork, leading to that official release in 2002.

Now it’s even more accessible. (At the time I’m writing this review, Shudder has it.) It sounds ridiculous for a 1992 movie to still be finding its audience 32 years later, but “Ghostwatch” exists in that perfect funnel of timing and circumstance to create this scenario. So maybe it’s a little embarrassing, but go ahead and discover this classic – better late than never.