Alfred Hitchcock released “The 39 Steps” – his prototypical light thriller about an innocent man on the run, and a woman caught up in a surprise romance with him – in 1935. Only two years later he delivered “Young and Innocent” (1937), an extremely similar story, even given the limited number of Hitchcock tropes.

I suppose this can be chalked up to the fact that there was no home video or TV movie channels; if people wanted to see an older movie, they were at the mercy of their local cinema. And the new “Young and Innocent” would sell more tickets than a re-released “39 Steps.”

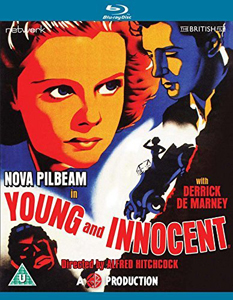

Although the similarities border on distracting, I’m in the minority in liking “Young and Innocent” more than the more convoluted “39 Steps,” which has international intrigue in the background. The reason is Nova Pilbeam, in what plays like an attempted star-making turn even though she’s only a few years removed from playing the kidnapped child in the original “The Man Who Knew Too Much.”

“Young and Innocent” (1937)

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Writers: Charles Bennett, Edwin Greenwood, Anthony Armstrong (screenplay); Josephine Tey (novel)

Stars: Nova Pilbeam, Derrick De Marney, Percy Marmont

The camera loves Pilbeam, as magistrate’s daughter Erica, and I could’ve seen her becoming cinematic royalty after this, but she never rose much beyond “child star” status. Erica is much more likable than the distrusting woman in “39 Steps,” as she believes Robert (Derrick De Marney) is innocent fairly quickly. She has a front-row seat, after all, for the idiotically lazy assumptions made by the justice system.

The duo is on the run from the law together – Robert by necessity, Erica out of belief in him – through most of the film. There’s room here for a grand romance, but “Young and Innocent” is hampered by the fact that Pilbeam is 18 and De Marney is 31. Their chemistry just doesn’t quite line up. Even though De Marney does that understated Hitchcock hero thing, I sense he is acting, whereas Pilbeam seems genuine.

The suspect has to be the sleuth

Writers Charles Bennett, Edwin Greenwood and Anthony Armstrong – working from Josephine Tey’s 1936 novel “A Shilling for Candles” – add light comedy via dialog. This is one of those films where, yes, our protagonist is on the run from officials who want to charge and prosecute him, but there’s an unspoken understanding between moviemakers and viewers that this is a world where all will be forgiven if he proves whodunit on his own.

We already know whodunit from the opening sequence, so the film is procedurally a howcatchem. But it’s a slow-moving one. Edward Rigby comes in with a good supporting turn as Will, a tramp who has been given a raincoat by the actual killer (George Curzon), who had aimed to discard evidence. So then it’s just a matter of getting Will in a position to identify the killer.

The climactic sequence at a dance hall – where the killer is playing the drums (in blackface, unfortunately) – is Hitchcockian in its staginess. But the director doesn’t have a lot to work with in the screenplay, so it feels like just a matter of time till Will spots the guy amid the crowded room.

When Pilbeam is on screen, which she often is, “Young and Innocent” is easy to watch. But her chemistry isn’t totally there with De Marney, and there are too many stretches where we’re waiting for the next thing to happen, rather than being delighted by a Hitchcockian twist. We’re in step with him rather than being a compelling half-step behind. Hitchcock’s competency is in place; his mastery (or should we say his ability to select masterful screenplays) isn’t yet.

RFMC’s Alfred Hitchcock series reviews works by the Master of Suspense, plus remakes and source material. Click here to visit our Hitchcock Zone.