The farther back in time I go with a throwback review, the more awkward it becomes as I must acknowledge a work’s place in history while also giving an honest recommendation to my blog’s readers. I decided to give Edgar Rice Burroughs’ “A Princess of Mars” (1912 in magazine form, 1917 in book form) a read after enjoying the 2012 film adaptation, simply titled “John Carter,” and encountered this conundrum.

“A Princess of Mars’ ” place in the continuum of sci-fi/space adventures can’t be denied. In his debut novel, Burroughs takes the baton from France’s Jules Verne and England’s H.G. Wells to become one of the earliest writers in the canon of American SF.

He invents John Carter, who has adventures on war-torn, or — to be more accurate – war-happy, Mars. It’s tempting to see Barsoom (the natives’ name for the Red Planet) as a tragic place. But various six-limbed green men (Carter’s first acquaintances, the Tharks, and their rivals the Warhoons) and red men (who resemble humans, like the people of Helium and their rivals from Zodanga) love war, or are at least neutral about it. As Rambo would say, killing is as easy as breathing on Barsoom.

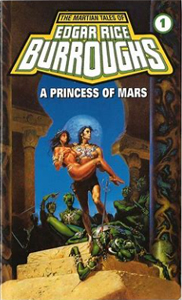

“A Princess of Mars” (1912)

Author: Edgar Rice Burroughs

Genre: Science fiction

Series: Barsoom No. 1

Setting: Arizona and Mars, late 19th century

Narratively, this isn’t for the sake of anti-war or pro-war commentary, although the author does value peaceful behavior. By some quirk, the female Thark Sola is a kind soul who feels attachment. And her father, Tars Tarkis, later learns the alien-to-him concept of friendship by observing John’s actions.

These Martians look familiar

Although the human-looking red people lay eggs (!), they are in every other way identical to Earth humans, including their capacity to feel love. John and titular Helium royalty Dejah Thoris – a visual template for every hot sci-fi princess to follow – immediately like each other because they are both so attractive.

Their major conflict is a confusing cultural one. John says he’d kill for Dejah, and that prompts her to give him the cold shoulder. It turns out if he kills the rival for Dejah’s affections, the prince of Zodanga, that is his right (there is no legal penalty for murder on Barsoom, which is perpetually on war footing); however, he can’t then marry her.

This leads to an odd narrative point wherein someone else has to kill the prince. The author still finds ways for Confederate veteran John – who can leap 40 feet at a bound like early pre-flight Superman, thanks to Mars gravity being less than Earth’s – to be a heroic warrior, as he mows through enemies with his broadsword.

Many of “A Princess of Mars’ ” oddities read more like flaws than curiosities. John is occasionally noted to be naked, as clothing is not part of Barsoom culture, yet he also conveniently pulls out gadgets like Batman. 2012’s “John Carter” found the natural way around this by dressing its characters in strategically placed armor while still showing off Taylor Kitsch’s and Lynn Collins’ muscled, sexy forms.

Burroughs’ early SF is of a type similar to Verne’s in that he uses his imagination more so than espousing scientific theories. He says the sun gives off nine distinct rays. One of the rays allows Barsoom’s air ships to float. And vaguely, the nine rays play a role in John mind-warping himself to Barsoom while simultaneously existing as a (temporary) corpse on Earth (luckily overseen by his nephew, who is in on the scheme).

Inspiration for ‘Total Recall’?

On the other hand, the neatest bit of Burroughs’ book that’s not in the 2012 movie is a piece of more legit SF. The atmosphere-creating plant on Barsoom is the only peaceful joint enterprise among the tribes, since without air they’d all die. When the atmosphere machine is threatened, we get a tense sequence very similar to what “Total Recall” (1990) would later do. (Although based on a Philip K. Dick short story, Mars’ artificial atmosphere was purely an element of the movie adaptation.)

After reading Burroughs’ novel, I’m even more impressed by what the 2012 “John Carter” did. The actors, alien designs and airship designs give the story cohesion, glueing together the stream-of-consciousness nature of the journal-style novel.

For now, I’m not going to go further into the 11-book Barsoom series, as opposed to how I went whole-hog into the French “Valerian and Laureline” comics (a space/sci-fi forebearer to “Star Wars” that launched in 1967) after seeing the 2017 movie version.

It’s understandable that 1910s readers marveled at how the Red Planet comes to violent, adventurous life in “A Princess of Mars.” And the novel’s place in the genre’s chain – leading to Buck Rogers, Flash Gordon, “Valerian” and “Star Wars” – is firmly linked. (Also note how “Star Wars” would riff on many Barsoomian words; I go into this in my review of “John Carter.”)

But a modern reader might notice Burroughs’ first novel is flattened under the weight of the followers who stood on his shoulders.