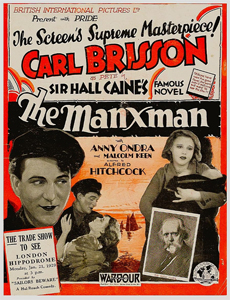

Alfred Hitchcock was not known for remaking other people’s films, but one example is 1929’s “The Manxman.” It follows a 1916 version, based on an 1894 novel by Hall Caine. The 1916 version rates higher (6.8 to 6.2) on IMDb, but it was lost in the infamous 1965 MGM vault fire, so those ratings are based on half-century-old memories of the site’s users.

While lost loves can turn from painful to wistful with the passing of time, Hitchcock’s “The Manxman” puts us right in the heart of an emotional love triangle. Oddly, the experience of watching it is pleasant, as we’re swept up in the broad (as per the necessarily theatrical style of the silent era) facial performances by the three leads, the languid but engrossing narrative, and the piano score added for the modern release (no credit information is available).

Comparing “The Manxman” to 1927’s “The Ring” – a more frivolous, comedic love triangle – illustrates this film’s emotional depth. Carl Brisson returns from that film to play the grinning, dimpled Pete, a fisherman who falls head over heels for bartender Kate (Anny Ondra), which is understandable since she seems to be the only woman who lives on the Isle of Man.

“The Manxman” (1929)

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Writers: Eliot Stannard (scenario), Hall Caine (novel)

Stars: Anny Ondra, Carl Brisson, Malcolm Keen

Pete’s longtime bestie, Philip (Malcolm Keen), is a successful lawyer on his way to becoming a magistrate on the island. He also loves Kate, but is reserved about it.

Honesty is the best policy (Spoilers)

Eliot Stannard’s scenario gives equal time to Pete, Philip and Kate, so we’re always dialed in to their feelings. For a while, “The Manxman” could be seen as a treatise on how being lovestruck can take over a person’s life. And by the end, it has become a sober reflection on how there is more to life than one relationship.

In between, though, it’s gripping enough to perhaps count as Hitchcock’s first twisty-turny narrative. And it gets my vote for his best of the silent era, edging out the more highly regarded “The Lodger” (1927). (SPOILERS FOLLOW.)

“The Manxman” includes one almost laugh-out-loud contrivance: Philip gets a telegram that Pete has died out at sea, but – inexplicably – that was a mistake. In the next telegram, Pete assures Philip he’s alive and well.

I forgive that silliness because the film is such an honest portrayal of how it would play out if Philip and Kate love each other but at the same time they care for Pete and don’t want to hurt him. Their empathy is such that Kate marries Pete upon his return, rather than confess that she and Philip are now in love.

That’s an outward solution, but not an inner solution, as “The Manxman” makes a fascinating case that doing the right, moral thing might in the end not be the right, moral thing to do. Honesty is the best policy, the film says.

The trouble with empathy (Spoilers)

It’s also interesting to note that the two people – Kate and Philip — who wring their hands over being morally upstanding are miserable while putting on the charade for Pete’s benefit. Pete, who follows his bliss so much so that he’s oblivious to the plain misery on Kate’s and Philip’s faces, lives a happier life. He’s not a bad guy, but he’s not bogged down by excess empathy.

Because of that, he ends the film with a smile – even though he ultimately loses Kate to Philip – much like Brisson’s boxing opponent does in “The Ring.” He’s made of stern enough stuff to move forward.

Meanwhile, Kate and Philip had thought they were doing the right thing, and Philip does another “right” thing – admitting his affair with a married woman and resigning as a judge – and is loathed by the Isle of Man’s populace. (Today, a government official so transparent and modest would likely be celebrated, such have the standards fallen.)

The “winners” in the love triangle are miserable, and the “loser” is happy. Inner feelings matter more than outside perception. Beat by beat, Hitchcock’s last fully silent film (the subsequent “Blackmail” would be done in both silent and sound) says romantic relationships are the be-all, end-all. But in the end, it convincingly undercuts that position.

“The Manxman” has sneaky, introspective depth. It’s telling that Caine’s novel hasn’t been adapted again since Hitchcock’s version. Perhaps everyone realizes this is as purely honest as a love triangle tale can get.

RFMC’s Alfred Hitchcock series reviews works by the Master of Suspense, plus remakes and source material. Click here to visit our Hitchcock Zone.