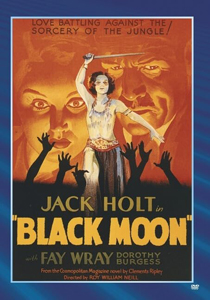

“Black Moon” (1934) is an outdated film — and most films with a voodoo subject share its awkwardness, from “White Zombie” (1932) to “Live and Let Die” (1973). But it has one or two redeeming qualities. Interestingly, it’s primarily about female struggles – mother, daughter and tag-along secretary – without being overtly about a female perspective.

What is the lure of island voodoo to a wife and mother?

“Black Moon” has good news and bad news for its central character, Juanita. The bad news? As a young girl, Juanita lost her parents to a voodoo sacrifice on a Caribbean island not too far from Haiti. The good news? She escaped back to the States, leaving her uncle behind. But there’s one more bit of bad news: A voodoo curse followed her.

Juanita grows up, marries Stephen and has a child, Nancy. But Juanita – played by Dorothy Burgess, famed for “Oh! Oh! Cleopatra” (1931) and “I Want a Divorce” (1940) — can’t escape the draw of the island. So, with her daughter in tow, she returns. Stephen follows.

“Black Moon” (1934)

Director: Roy William Neill

Writers: Clement Ripley, Wells Root

Stars: Fay Wray, Jack Holt, Dorothy Burgess

The locals are so pleased with their arrival, they elect Juanita their voodoo goddess. Invariably, this entails a great deal of workday stress. The nonstop voodoo drums add to the tension. It’s exhausting to perform all those dark rituals and human sacrifices; Juanita’s ties to her spouse and daughter are stretched to the breaking point.

Either the voodoo’s dark rituals or nuclear family values must give way. It’s predictable that the father-husband is going to have to nip this nascent career-climbing in the bud in order to save his daughter from the corruption of a mother who explores challenges outside the home.

“Black Moon” was originally a throwaway story by Clement Ripley in Cosmopolitan (First published in 1886, it was a literary magazine before it switched to being a women’s magazine in 1965). The story’s reliance on the otherness of native traditions is terribly outdated, truly outworn and tremendously offensive. A racist reading is unavoidable, and it results in a film that is despicable as well as unwatchable. Stephen literally warns Juanita: “The natives are restless.” No wonder.

Voodoo as trauma

The film’s exploration of Juanita’s trauma, however, is interesting. If one replaces “voodoo” with “trauma,” a more watchable film emerges. In a way, Juanita is re-living her childhood on the island. The secondary effects on her young daughter are skillfully portrayed; she’s torn between competing family dynamics. But these slim merits don’t quite rescue the film.

If, in the final analysis, “Black Moon” is still watchable, it is because of Fay Wray. Her character –Stephen’s secretary, Gail – is almost an afterthought. Her only necessity to the plot is to send the wireless message to urge Stephen to the island.

One has the feeling that the writer was instructed to craft a script in which Wray could appear if a contract could be negotiated but easily deleted if negotiations failed. She’s nearly as expendable as Nancy’s stuffed bunny, Gus (in an uncredited role).

Still, Wray lends the film an emotional and moral core. She’s an unlikely heroine, but a fine one. “Black Moon” is a tough pill to swallow when it comes to race and multiculturalism. But Wray gives it a certain sweetness.