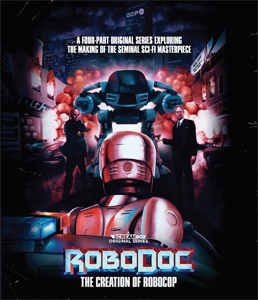

Thanks to crowd funding and documentary makers’ better sense of the size of their potential audience, we’re getting in-depth docs on classic entertainment like never before. Impressively gathering up all the major cast and crew except those who have died (actors Dan O’Herlihy and Miguel Ferrer) and reclusive practical-effects legend Rob Bottin, “RoboDoc: The Creation of RoboCop” (2023) fills in a key gap in film history.

Previously, the only documentary on this groundbreaking cinematic mix of violence and metaphor about major societal issues (plus the manner in which TV news chronicles those issues) was a 22-minute piece from 1987, concurrent with “RoboCop’s” release.

Writer-directors Eastwood Allen and Christopher Griffiths show how blood, sweat and tears – and then more blood – made for a shoot everyone labels difficult. Yet everyone looks back on it fondly, because it was successful, and continues to be thanks to the timeless social satire and the sci-fi treatment of how a soul makes a man.

“RoboDoc: The Creation of RoboCop” (2023)

Four-episode documentary miniseries

Directors: Eastwood Allen, Christopher Griffiths

Writers: Eastwood Allen, Christopher Griffiths

This week, RFMC looks at the films and TV shows of the “RoboCop” saga.

While “RoboCop” is not dated in those ways, it is dated in the sense that mid-budget movies generally aren’t made anymore. The budget was $10 million, the same as “Star Wars” 10 years earlier. As with the George Lucas film, “RoboCop” sits in that magical middle ground wherein there’s enough money to make a great movie — not so little that it looks cheap, not so much that it’s slick product.

The right amount of insanity

Ingenuity is needed, and “RoboDoc” illustrates how Dutch director Paul Verhoeven did little things to make the film great, such as emphasizing Murphy’s dream as a soul-awakening. Another example: He had the metal hero “walk on water” at the final showdown to emphasize the RoboCop-Jesus parallel; perhaps only Verhoeven saw the link, but it subtly infused the film with depth.

Although everyone praises his vision today, Verhoeven was hated on the set. That’s a common refrain for directors on groundbreaking films (see also Ridley Scott on “Blade Runner”), but it seems warranted. Hearing these tales of dangerous management of squibs and reckless positioning of actors in the explosion-laden street shoot-up, it’s amazing no one was killed.

It’s humorous to see clips and stills of the energetic director on the set followed by modern interviews with the octogenarian wherein he hasn’t lost his childlike enthusiasm for splattering the screen with fake blood.

But also, we learn that he shot the screenplay by Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner straight-up, trusting that it would have meaning even if he (just learning English and American culture) didn’t understand the details. In a funny story, an actress who played an escort in the “Bitches, leave” scene says Verhoeven politely called her and the other actress “bitches” because he didn’t understand the derogatory context.

A viewer comes away thinking it was the professionalism-tinged craziness of almost everyone that made “RoboCop’s” success possible. Peter Weller – and more so, the stories of how 1986-vintage Peter Weller insisted on being called “Robo” on the set – might have a pretentious air, but hearing him recount his eureka moment when he grasped the point of “RoboCop” makes it fresh again.

Laser-focused on the original film

Paul M. Sammon, a film scholar who was an Orion executive at the time, also discusses “RoboCop’s” meanings, thus allowing Allen and Griffiths to stick with the modern docu approach wherein there’s no narrator; the interview subjects propel the narrative themselves.

“RoboDoc” generally follows the flow of the movie’s storyline. So you get the pre-production stuff (including things Neumeier and Miner didn’t copy – “Iron Man,” “Judge Dredd,” “The Terminator” – even though it seems they might have) first and post-production stuff like the battle for an R rating (instead of X) last. But we pop in for insights into special effects and sound effects here and there.

The docu unnecessarily dresses up some of the sit-downs, adding digital effects of gunshots when Weller is mimicking firing a prop gun, or cutting to shots of Verhoeven grinning when someone else tells a wild story about him. The editing could’ve been more judicious; at one point Nancy Allen’s praise of Weller’s acting is awkwardly inserted after a chronicle of stunt man Russel Towery’s work in the battle against ED-209.

“RoboDoc’s” misfire, in my opinion, is not delving into spinoff materials beyond giving them lip service. Analyzing the three follow-up movies, two live-action TV shows, two animated series, comics, toys and games was never in the purview of Allen and Griffiths, but since the total runtime is more than 4 hours, I would’ve liked a higher percentage to be about the franchise as a whole.

Granted, at the end of an analysis of the whole saga – as I’ve found in my “RoboCop” redux blog series – we’d reach the same conclusion: The original film was magic in a bottle (or rather a combat-robot shell). While there’s been additional money made from the spinoffs, all the central themes and arcs are in the original movie. If “RoboCop” (1987) fans watch a second “RoboCop” product, it should be “RoboDoc.”