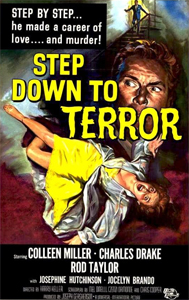

“Step Down to Terror” (1958) is Alfred Hitchcock’s “Shadow of a Doubt” (1943) put into a blender with Fifties sitcoms where father knows best … even if he’s a serial killer. Donna Reed was considered as the female lead before Colleen Miller ably stepped in.

(SPOILERS FOLLOW AS I COMPARE THE TWO FILMS.)

Director Harry Keller opens this remake (with a mildly tweaked screenplay, but still drawn from Gordon McDonell’s story “Uncle Charlie”) with a shot of a broken stair on the outdoor staircase of the small-town California home.

It’s Hitchcockian only in the sense that we zero in on something that will later matter, Chekov’s Broken Stair. It’s like blunt information more so than a sinister, stylish revelation. “Step Down” may not exactly assume viewers are idiots, but it holds our hand five years before the Beatles wanted to do the same.

“Step Down to Terror” (1958)

Director: Harry Keller

Writers: Mel Dinelli, Czenzi Ormonde, Sy Gomberg; Gordon McDonell (original story)

Stars: Colleen Miller, Charles Drake, Rod Taylor

Different enough to not embarrass the actors

Later, when Helen (Miller) looks up the newspaper article and finds the Strangler’s last victim had the initials J.D., I knew she’d look at her ring — gifted to her by Johnny (Charles Drake) — and linger on those initials. And that’s indeed what happens. (Helen is Johnny’s widowed sister-in-law. But still there’s an “Uncle Johnny” flavor to him because he’s the uncle to her son, Rickey Kelman’s Doug.)

I don’t want to rip into “Step Down” too badly, as the premise is strong enough that it’s always interesting to see actors play it out. It’s a well-shot costume drama with good actors giving performances at the same breadth as the crisp 76 minutes of material.

By making the screenplay different enough (most notably, by having a conflict between a widowed sister-in-law and a single brother-in-law, rather than an uncle and niece whose closeness is a little wiggy), the three writers only put Drake in a cringey position once. He gives a tamer version of Jospeh Cotten’s famous speech about how people are animals and rich widows in particular are swine. Drake gets off easy compared to Vince Vaughn having to re-play every one of Anthony Perkins’ scenes in “Psycho” (1998).

It’s the one time I can see Drake is merely acting, because the screenplay generally doesn’t hint that Johnny loathes humanity; it emphasizes his mental illness. Johnny was in a bicycle accident – never discussed in detail by the family – when he was a kid, and he still gets headaches. He’s a Jekyll and Hyde; he can’t help his mood swings. If Uncle Charlie is Spike (able to be good if he tries hard), Johnny is closer to Angel (totally at the mercy of the loss of his soul).

In one minor way, the screenplay reacts to a flaw with “Shadow.” When federal investigator Mike (Rod Taylor) tells her they’ve caught a suspect “back East,” Helen wants to know the full details. Did this Eastern suspect confess? No, he was killed resisting arrest, but his colleagues must be satisfied because they closed the case. “Step Down” at least hangs a lampshade on this plot oddity.

The story operates in the light, not the shadows

Clearly, Johnny will get off scot free as long as Helen says nothing, but she has a sense of justice so she pushes the matter, leading us into the climactic final act. As a general rule, I like crisper storytelling, but Hitchcock knew how to play the margins – to present a story clearly, but to leave in some oddities. He guided the audience but didn’t assume they were dumb.

Young Charlie has agency like Helen does, but it’s fraught with nuance about how she had always loved and admired Uncle Charlie. Plus, she is a teenager, not expected to be a heroine. And there’s also that implied incestual love between the Charlies, but only for viewers who want to go there. “Shadow” has layers that “Step Down” makes sure to avoid.

Helen – raising her son with the help of her mother-in-law (Josephine Hutchinson) — simply acts like a sensible adult, which is admirable but not as interesting; her decision is dangerous but not difficult. She’d be open to a romantic bond with Johnny, but that depends on him being a good person rather than a traveling serial killer. If he’s the latter, that’s a deal breaker.

(END OF SPOILERS.)

I guess folks in the Fifties wanted the edges sanded off their dark family and relationship dramas – or, more likely, Hollywood thought they did. Perhaps rightly so. Also in 1958, Hitchcock made “Vertigo,” but that wasn’t an immediate hit.

“Step Down to Terror” is a business decision of a movie. No matter how much deep-bass stock music is coated onto key scenes, it’s a step down in evoking terror — a costume drama where the poisoned milk doesn’t glow and where one stair breaks but the rest stay safely intact.

RFMC’s Alfred Hitchcock series reviews works by the Master of Suspense, plus remakes and source material. Click here to visit our Hitchcock Zone.