“Suspicion” (1941) is driven by two movie stars, Cary Grant and Joan Fontaine, acting the heck out of their roles in order to make an absurd story remotely believable. It’s not one of Alfred Hitchcock’s best films, but it’s mesmerizingly watchable and a great example of how he worked around the censors.

The Hollywood mores of the time might’ve had somewhat of a point, though. The studio argument goes that Grant can’t play a murderer; it would damage his image. My gut reaction is studios thought 1941 audiences were stupid, but there’s another angle.

If people went into “Suspicion” feeling like they already know Johnnie because he’s played by Grant, then some of the work is already done for the storytellers. Same goes for Lina actress Fontaine, who played fragile in 1940’s “Rebecca.” So we have a pathetic, likeable gadabout and a sweet, vulnerable woman. Their backstories are ready-made.

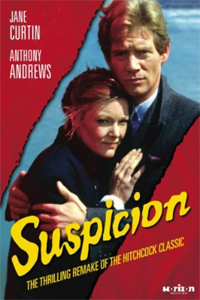

“Suspicion” (1988)

Episode of PBS’ “American Playhouse”

Director: Andrew Grieve

Writers: Barry Levinson, Jonathan Lynn (teleplay); Joan Harrison, Samson Raphaelson, Alma Reville (original screenplay); Anthony Berkeley (play)

Stars: Anthony Andrews, Jane Curtin, Jonathan Lynn

By 1988, the release date and setting of the remake for “American Playhouse” (PBS), we still had persona-driven movie stars, but few who brought a totally established backstory to every movie.

Director Andrew Grieve’s “Suspicion” casts Anthony Andrews and Jane Curtin. It’s believable for a half-second that Lina might consider looking at Johnnie, let alone marrying him. This is only because she overhears her parents talking about how it’s perfectly fine if Lina grows into an old spinster.

The Forties awkwardly meets the Eighties

Lina understandably takes this negatively due to their harsh word choice, and it’s plausible that this could be a shocking prompt for her to move out of the house and get a job rather than living off her allowance, since she appears to be 30 (Curtin’s age at the time). Granted, sitting around reading coffee-table books about Hitchcock is a great life, but at least do it in your own flat.

But Lina seems to think marriage is the only path to a life separate from her parents (even though we’re in the Eighties now), so she’s the first to say “I love you” to Johnnie. It’s less believable than when Padme says it to Anakin in “Star Wars: Episode II.” I want to say “You do????!!!!” to the screen.

Andrews effectively conveys that Johnnie is an inveterate schemer, working harder to not have a job than most people do at their actual jobs. After Lina’s spark to start a life with Johnnie, her naivete about Johnnie’s activities is never believable; she doesn’t ask about his finances till after she ties the knot. Curtin exudes intelligence, and the filmmakers do nothing to dumb Lina down; when we and Johnnie meet her, she’s reading a textbook. It never adds up.

Andrews doesn’t play pure menace; he goes for the back-and-forth thing. But still it’s pretty obvious that everything Johnnie does is a scheme. It’s not so much a question of whether he loves Lina or not; he’s simply not a stable person. Lina can and should do better; I’m a hopeless romantic and even I recognize this.

A quick shout-out must go to Jonathan Lynn (who also co-writes with Barry Levinson). He does a magnificent Nigel Bruce impression as Beakie, Johnnie’s best friend who is genuinely naïve (rather than naïve because the script says so, as with Curtin’s Lina).

A missed opportunity (Spoilers)

(SPOILERS FOLLOW.)

Writers Levinson and Lynn stay faithful to the 1941 screenplay the whole way, which might seem smart but it’s actually unfortunate. Grieve shoots the same ending Hitchcock did: It seems Johnnie is going to kill Lina and make it look like a car accident, but no, he’s morose because he was thinking of killing himself with poison. Lina sees him in a new light and they live happily ever after.

Defenders of the abrupt ending rightly note that it’s not really “The End,” it’s “To be continued” (off screen). Lina is likely caught in an endless cycle of questioning her husband’s motives. It’s a grotesque, magnetic tragedy, at least in artistic intent.

Regardless of whether you like it, “Suspicion” is among the most interesting Hitch films to talk about, because he toyed with alternate ways to end the film before settling on a version that placates the censors. One intriguing alternative finds Lina drinking poisoned milk, unable to live with loving a man who wants to kill her. But Johnnie would then post a letter she had written, which reveals Johnnie as her murderer; thus he ironically seals his fate, and justice is satisfied. (But the goal of Grant maintaining his good-guy image is shattered, so that ending didn’t fly.)

“Suspicion” 1988 could’ve salvaged some coolness points by going with that alternate ending. Sure, it wouldn’t have rung true – we’d still say Curtin’s Lina never truly seemed to be in love – but it wouldn’t be any worse than repeating Hitchcock’s ending. It would’ve been a wonderful surprise.

What was “Suspicion” 1988 trying to hold on to? By that point, it’s credibility as a good film was on par with the credibility of Johnnie’s and Lina’s marriage.

RFMC’s Alfred Hitchcock series reviews works by the Master of Suspense, plus remakes and source material. Click here to visit our Hitchcock Zone.