Fifty years later, “The Conversation” (1974) remains a timely warning (or maybe now it’s just a portrayal, as the time for warnings has passed) about living with surveillance devices all around us. The film is also very much of its time — both in the sense that the technology was new, and in the surprising fact that it’s about the personal, psychological price of spying. The plot actually does not involve the government.

Writer-director-producer Francis Ford Coppola’s film between the first two “Godfather” entries makes a mark even amid the golden age of neo-noirs about spying, plus one of the most famous government spying scandals, Watergate.

Mom-and-pop spy shop

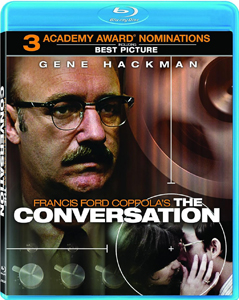

But while it has an ingenious plot twist at the end, “The Conversation” is not propelled by plot or mystery. Slow-moving by modern standards but nonetheless magnetic, the film is instead driven by Gene Hackman as Harry. At first blush, Hackman simply looks worried and thoughtful, but there must be something more to it, because I sympathized with his character even though he’s a professional freelance surveillance expert.

“The Conversation” (1974)

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Writer: Francis Ford Coppola

Stars: Gene Hackman, John Cazale, Allen Garfield

Another thing that makes it stand out is Harry’s work environment, a caged-off portion of a floor of what appears to be a decommissioned parking garage. I can’t recall another movie setting quite like this. He has an apartment, too, reminding us that 1, this was a different time in the San Francisco real estate market, and 2, if he makes $15,000 for one spying operation, he can afford two rents.

Emphasizing his workaholic nature, Harry has a cot at his workshop, and – in the film’s devasting centerpiece sequence for this man questioning his purpose and morality – he throws an impromptu party there for industry colleagues. This man who has learned to trust no one is tested by beautiful Meredith (Elizabeth MacRae). Either Harry is an inexplicably natural ladies’ man in the way of old movies, or Meredith is not to be trusted.

The tech is fascinating too, in the early days of technology-based spying. Clearly, a lot of research went into the details; viewers of the time must have wondered what was possible and what was science fiction. At an industry conference, Harry’s friend/rival Bernie (Allen Garfield) unveils a device that can turn someone’s phone into a tape recorder by playing a harmonica note.

Modern viewers will draw a parallel to agencies listening in to people’s cellphone conversations and turning on their laptop’s cameras (something shown in 2016’s “Snowden”). Indeed, I initially assumed Harry is a government agent, but he actually is an independent contractor. When realizing that, I assumed his clients – with contact man Martin played by Harrison Ford in his brief pre-“Star Wars” character-actor phase – are the government. Again, no, this is entirely a private matter.

An intimate film about a supposedly impersonal craft

That makes “The Conversation” more personal; indeed, many films about government spying emphasize the depersonalized nature of metadata collection – and that impersonal nature is why defenders of the spy state argue it’s OK. Perhaps this helps government agents sleep at night too.

Coppola has us sympathizing with spy targets Ann and Paul (Cindy Williams and Michael Higgins) as Harry relentlessly plays back the recordings he got at a busy San Francisco square by combining multiple tracks. The line “He’d kill us if he got the chance” rings with a deeper level of chills when we learn its full meaning, and the twist is plausible due to the not-entirely-perfect nature of recordings amid a noisy crowd.

“The Conversation” smoothly employs symbolism, like when Harry smashes his religious figurines to look for electronic bugs. While compelling for all the reasons mentioned above, the film makes us sad about the immoral and dehumanizing use of amazing new technology.

What’s impressive is that the sadness is not abstractly intellectual, as is the case in many spy thrillers. (This one is not an action movie, although the potential for violence looms over it, similar to “All the President’s Men.”) As the iconic closing montage in Harry’s apartment shows, being a spy has stripped away his own sense of privacy, and his own small slices of life where he can be happy.

It seems like “national conversations” about important issues don’t generally happen, or at least don’t lead to results (OK, not to the results I want). So maybe the point for conversation has passed, but “The Conversation” is still worth watching as a portrait of the beginning of the end of privacy.