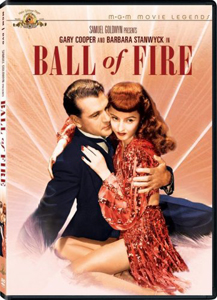

“Ball of Fire” (1941) combines the “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” fairy tale with noir with slapstick, and it’s worthy of a smile for 1 hour and 51 minutes. Must be written by Billy Wilder. Even while establishing his reputation early in his Hollywood years, Wilder (working with two other writers) shows he knows a good premise and how to stick with it.

Director Howard Hawks – considered to be among the greatest directors who didn’t favor a particular genre – then supplies the rhythms and pacing needed for this type of comedy.

New slang

Despite not being a native English speaker, Wilder (with co-screenwriter Charles Brackett and co-story writer Thomas Monroe) pens one of the best explorations of slang ever put on film. I suspect it’s a combination of real 1941 slang with some exaggerations. Bertram Potts (straight man Gary Cooper) and seven other professors live in a large house where they’ve been commissioned by the late inventor of the electric toaster to write the definitive encyclopedia of human knowledge.

“Ball of Fire” (1941)

Director: Howard Hawks

Writers: Billy Wilder (screenplay, story), Charles Brackett (screenplay), Thomas Monroe (story)

Stars: Gary Cooper, Barbara Stanwyck, Oscar Homolka

As they arrive at the S’s, Potts’ assignment is slang, and he realizes he’s out of the loop. It’s highly amusing to see this naïve innocent wandering about the city with a notebook as newspaper hawkers, horse-track bettors, mobsters and entertainers spew street talk with such rhythmic patter that “Ball of Fire” almost becomes a spoken musical.

At a club, he tries to learn the meaning of “boogie” and related words as Sugarpuss O’Shea (Barbara Stanwyck) sings “Drum Boogie,” backed by a swingin’ band. He never gets a straight answer to that one. Boogie just means boogie. But later, his panel of slang experts walks him through the meaning of “corny” and its offshoots.

The two leads meet in a clever instance of mistaken identity: The professor knocks on her dressing room door soon after she’s been warned by mobsters (with whom she is loosely associated) that the D.A. is after her for what she knows. I love the sequence where Sugarpuss tells Potts to leave in about 10 different forms of slang and his eyes light up at this potential source of knowledge.

Sneakily romantic

“Ball of Fire” also stands as an early example of Wilder pushing things to the limit of what censors allowed at the time, particularly via the budding romance between Sugarpuss and Potts. Like his seven colleagues and their matron, he’s flustered by her sexuality, which in 1941 was suggested by the removal of a stocking and the flashing of some leg. (In any era, Stanwyck is sexy in this role.)

It’s super cute when Potts admits to being affected by the brush of her breath against his ear and the glow of the sunlight in her hair as they work on his slang article for the encyclopedia. It doubles as a way to show Sugarpuss – accustomed to the blunt street behavior of previous paramours – finds Potts to be an appealing contrast. Plus, Cooper and Stanwyck happen to have sizzling chemistry (although I do feel bad for Mary Fields’ Miss Totten, who likes Potts and might be more his speed in the long run).

“Ball of Fire’s” story gets a little big for Hawks to handle when the final conflict features the professors held at gunpoint by the mob’s henchmen. The director decides to go with physical and spatial comedy (quite popular just before this time) to get out of the fix. The fight between Potts and his rival for Sugarpuss’ affections is so poorly choreographed that the film settles for limbs flailing into the camera frame.

While this is a purposeful choice, in retrospect it’s an overcompensation to stay safely in the realm of comedy. Numerous later Wilder films proved that believable action – even flying bullets or fists, and even murder (consider that the narrator of “Sunset Boulevard” is a dead man) – can exist in a comedy without it being jarring. Audiences can recalibrate if we’re into the story and characters.

So the grin on my face from early in “Ball of Fire” is more of a pleased smirk by the end. But the film stands as a strong collaboration between two rising filmmaking greats, a couple of stars, and a premise you won’t find in any ole movie.

Wilder Wednesdays looks at the catalog of legendary writer-director Billy Wilder.