With “The Winslow Boy” (1999), writer-director David Mamet is as much using his name recognition as he is using his skill to bring an important story to the public’s attention. Based on a real legal case, the film is adapted from Terence Rattigan’s 1946 play, which was made into a film two years later, co-written by Rattigan.

The 1948 film rates a few percentage points higher (7.7 to 7.4) on IMDB than Mamet’s version. Yet this adaptation is important because it brings a crucial story to a wider audience, and it’s also impeccably directed in Mamet’s no-moment-wasted 105-minute style without sacrificing any turn-of-the-20th-century British affectations.

Taking on the Crown

At this point in British law history, the Crown couldn’t legally be found to have made a mistake, but there was a small chance of recourse for defendants called a “petition of right.” However, it was still difficult for an individual to win a case against the government, because you still had to shame a body of elected officials into doing the right thing. Surprisingly, if you’re looking for a gripping legal drama, you do get it in “The Winslow Boy,” but without a single scene set in a courtroom.

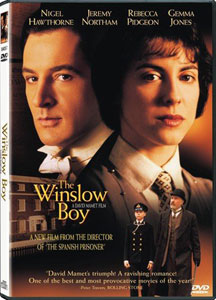

“The Winslow Boy” (1999)

Director: David Mamet

Writers: Terence Rattigan, David Mamet

Stars: Rebecca Pidgeon, Jeremy Northam, Nigel Hawthorne

Early on, the film establishes the innocence of Ronnie (Guy Edwards), who has been expelled from his youth naval academy, found guilty of stealing a postal order and cashing it. We know he’s innocent because he says so to his dad, Arthur (Nigel Hawthorne), and it’s clear that no lies can go undiscovered in this father-son relationship.

Later, lawyer Sir Robert Morton (Jeremy Northam) employs a series of tricks in his interview with Ronnie, designed to catch a guilty person; the boy passes that test, too. Additionally, through snippets of newspaper articles and cartoons, we know public perception is on the boy’s side.

So, interestingly, the drama isn’t about the court case, but about getting the case heard in a courtroom in the first place. It’s so difficult that veteran lawyer Morton considers “justice” and “right” to have distinct meanings. “The Winslow Boy” is a fascinating historical document about the justice scales in Western governments tipping a micrometer toward individual rights, and while the ultimate victory is no small thing, it’s the uphill battle that’s illustrative.

For all the great legal drama, the film is also about how the case affects the characters, and Mamet certainly knows this, as the bulk of the conversations (I say “conversations,” rather than “action,” as this story’s stage roots are clear) take place in the Winslow household. “The Winslow Boy” may start off as a stodgy period piece where we soak up the stuffed-shirted and precise ways decently well-off British people behaved back then, but it’s not long before everyone shapes into distinct characters.

A classic patriarch

The classic patriarch who is mindful of the family’s financial situation, Arthur’s health deteriorates over the course of the case. His wife, Grace (Gemma Jones), wonders if it’s all worth it. Even more strikingly, daughter Catherine (Rebecca Pidgeon) could lose a solid suitor, John (Aden Gillett), unless the family drops the case.

Desmond (Colin Stinton) is a desperate backup plan; he comes off as a rock-solid guy as far as I can tell, but I guess the fact that he’s always loved Catherine is a horrific turn-off to her. At any rate, it’s clear that marriage is crucial for women of the time to lead secure lives – or at least that’s the accepted mode of thought.

The interplay between Catherine and Morton is always compelling in that classic period-piece manner where the woman has her subservient place in society yet is also headstrong enough to affect a man who is fascinated by her. That said, Catherine volunteers at a women’s suffrage group, and she’s not as playfully amused by Morton’s assertions that equal rights are “a lost cause” as she pretends to be. As good as the whole cast is, the Catherine-Morton interactions are particular highlights because of the multiple layers of meaning.

Because he didn’t write the movie – he merely adapted it – it’s tempting to see “The Winslow Boy” as a less important Mamet work, a curiosity among his catalog. But as a director, he clearly gets everyone on the same page in terms of acting approach, which, yes, is in the old style, but it’s also tightened up, featuring some people speaking over each other and always maintaining forward momentum.

Before this film, there was a real perception that “The Winslow Boy” was a dusty stage relic; for all his clout, Mamet couldn’t get backers for a New York run of the play, and he decided a modestly budgeted film was the better approach. As a result, we now have a modernized-yet-faithful document of this important historical case.