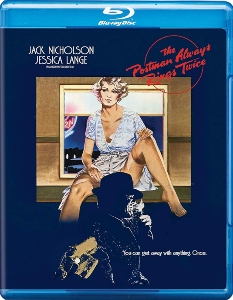

Film being a director’s medium, “House of Games” put David Mamet on the map in 1987. But his big-screen career launched earlier in the decade with “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (1981), in which he adapts the 1934 novel by James M. Cain. (It was also adapted in 1946.)

The film portrays an up-and-down relationship between drifter Frank (an intensely watchable Jack Nicholson) and roadside restaurant cook Cora (Jessica Lange), so it’s appropriate that it sometimes plays like an uneasy marriage between Mamet’s screenplay and Bob Rafelson’s direction. While it’s likely Mamet would’ve made different decisions if he was directing, “Postman” is by no means a blight on his resume.

Beautiful 1930s California

Rafelson and his team beautifully capture rural California in the 1930s and the era’s noir aesthetic – for example, Michael Small delivers too big (by today’s standards) music cues as the dramatic moments approach – in a movie that isn’t a whodunit, but rather a “Will they get away with it?”

“The Postman Always Ring Twice” (1981)

Director: Bob Rafelson

Writers: David Mamet, James M. Cain

Stars: Jack Nicholson, Jessica Lange, John Colicos

Mamet’s specialty of detailed con plots pops up here and there, but these threads are quashed by Rafelson’s emphasis on the Frank-Cora relationship and the central plot, which is a straightforward con: Frank and Cora aim to kill Cora’s husband (John Colicos as the very killable Greek drunkard Nick) and make it look like a car accident.

In this grand morality play, a viewer (assuming they are decent person) won’t relate to Frank’s and Cora’s actions, but there are enough human moments where we sympathize with them despite ourselves. For one thing, Nick is annoying as heck, as we see from his pride over his new robe (meanwhile, he never gets Cora anything) and the general way he views Cora as a servant.

For another, “Postman” plays a neat trick wherein neither Frank nor Cora is wholly the instigator; rather, they pull each other along. When Nick goes into town for supplies, Frank – now employed as the mechanic – flips the roadside diner/service station’s sign to “closed” and gets rapey with Cora. She eventually submits, and the sex scene is long enough to make a viewer reflect on the social expectations and role of a woman in the 1930s.

Next, Cora suggests a scheme to kill Nick. We already know Frank has some con-man blood in his veins; as “Postman” opens, he pretends to have been robbed in order to scam a free meal from the diner. Still, it seems likely that the beautiful Cora – not a longer con – is the reason he takes the mechanic job. Cora is the femme fatale, and Frank is genuinely surprised when she suggests murder.

A bizarre romance

For all the time Rafelson spends on the many intimate scenes between Frank and Cora – which do indeed illustrate their bizarre relationship, wherein Cora often tries to fight him off before getting into it – he is much less interested in “Postman’s” most complex con, perpetrated by the couple’s lawyer, Katz (Michael Lerner). It unfolds so briskly that I’d have to rewind and watch it again to get the details, but essentially Katz nets himself a big payday by playing the many sides off one another.

Frank and Cora get off, but they’re under probation and still poor, as Nick’s life insurance payout has been absorbed by the lawyer’s scheme. And then we’re back in the territory Rafelson is interested in: the relationship.

I’ll say this for the second half of the 2-hour film: I didn’t know precisely where it was going. It meanders like one of those slice-of-life movies that fades off into the credits, but then it actually does deliver the big statement we’d expect from a 1930s-set noir.

Ultimately, “The Postman Always Rings Twice” is slighter than, say, “Chinatown” – with which it would pair nicely in a Nicholson double feature – but the core relationship is so charged that it lights up the 2 hours. A 100-minute version that emphasizes the cons and de-emphasizes the sex scenes would be more Mametian, but when Nicholson and Lange are so on their games, it’s hard to quibble with Rafelson’s choices.