The formula of using a Philip K. Dick short story as a foundation for an action film had been established by the time director John Woo got around to making “Paycheck” (2003). It’s the earliest PKD story – written in 1952, published in 1953 — to be turned into a film. Writer Dean Georgaris (“Lara Croft: Tomb Raider — The Cradle of Life”) takes the hookiest part of the story – a person sends clues to his future self before his mind-wipe – and builds a fairly engaging mystery-actioner around it.

Not quite a mystery, not quite SF

Looking at “Paycheck” as a mystery-actioner, the SF stuff seems like window dressing; looking at it as a SF film, the action seems to distract from what it could have been. While it’s not off base to say that “Paycheck” is “just another 2000s action movie,” it has slightly more to offer than a mid-level film of the time.

Ben Affleck – committed to being an action hero at this point in his career — sells most of this material as Jennings, who has been employed in the sketchy arena of reverse-engineering rivals’ technology. He comfortably slots in next to Arnold Schwarzenegger, Tom Cruise and Gary Sinise among PKD cinematic heroes who are confused as hell as they try to save their own skin – and usually the world, too.

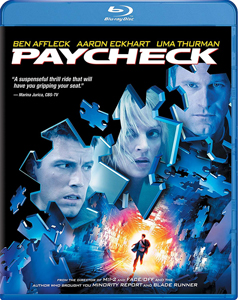

“Paycheck” (2003)

Director: John Woo

Writers: Philip K. Dick, Dean Georgaris

Stars: Ben Affleck, Aaron Eckhart, Uma Thurman

Jennings is not the most upstanding person, but he’s a better guy than Aaron Eckhart’s Rethrick and Colm Feore’s Wolfe, who intend to backstab him.

Affleck doesn’t have great chemistry with Uma Thurman as Rachel, his love interest who is a botanist (I’ll spare you the Poison Ivy jokes). “Paycheck” does that thing often seen in Thurman roles where she’s painted as being a bombshell, the woman of every man’s dreams. The actress isn’t ugly, but she is basic looking, and it would’ve worked better if she was in more of a “Who me? You like me?” type of role.

Paul Giamatti adds a needed “Hey, I like that guy” element as Shorty, Jennings’ best bud, the one guy he can trust.

More action than plot

Once we learn that the envelope of 20 items (up from seven in the story) are necessary to Jennings’ plan to free himself from Rethrick’s clutches, get himself to safety and learn about the dangerous future-seeing Machine, “Paycheck” is an amiable thriller. It’s more into the action than the plot; indeed, after a wild multiple car and motorcycle chase, a henchman makes a quip about whether Jennings saw that in his vision of the future.

If we pause at any point during “Paycheck” and think about what’s happening, it collapses. The most interesting part of the plot is something that happens off-screen beforehand: Jennings, before has three years of his life erased in a mind-wipe, chooses these 20 items to send to his future self.

The logic problem is this: Jennings can merely see into the future, he can’t travel into the future or manipulate it. So that means he sees that his future self has all of these items, all of which are crucial for his success. Then he sends himself the items. So the future determines the past. While that might be cool in a brain-teaser sort of way, it also makes no sense.

The time-seeing device (it’s a Time-Scoop in PKD’s story, “The Machine” here) is barely explained. A since-murdered genius at the company that Jennings had stolen this machine from developed a lens that can see around the curve universe. Using this lens, you can see yourself – in the future.

That’s a fun theory, but “Paycheck” doesn’t come close to explaining how the lens can see into the future, rather than the past. (When we look through telescopes, we see stars as they existed in the past, since it takes time for light to travel to us.) And we get no explanation, even in mumbo-jumbo terms, of how The Machine can pinpoint specific people, times and locations, and catalog them in a database for playback.

Sketchy view of the future

The seeing-into-the-future element is sketchily defined in both versions, but there’s something about a short story where it can get away with it. PKD also has deeper themes to mull. Georgaris trades in PKD’s prescient commentary on corporatism and oligarchy for a vague philosophical message about how people who can see the future have no future, and how a knowable future is horrible for all mankind.

Jennings screams this realization for the audience – and we see future newspaper pages showing nuclear bomb blasts — but the threat is so big that it’s actually yawn-worthy. OK, so the future will be one of constant pre-emptive war if this machine is allowed to exist.

But that’s what the present day holds anyway. The entire US drone-bombing program, which started around the time of “Paycheck’s” release – and which has a very Dickian irony at its core — is based on the premise of killing terrorists before they carry out an act of terror.

I had some fun with “Paycheck,” though. Georgaris gets mileage out of the mystery element of PKD’s story, Affleck is a likable lead and the action is solid. Plus, Woo’s signature white dove makes a forced appearance that we can all chuckle at.