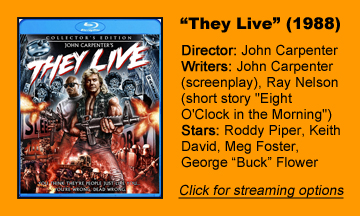

Writer-director John Carpenter’s “They Live” (1988) is technically about aliens infiltrating Earth and posing as humans, but the metaphor is so thinly veiled it’s hardly a metaphor at all. Drifter John Nada (Roddy Piper) recognizes these people are aliens by putting on magic sunglasses that reveal their zombie-faced nature.

The aliens are stand-ins for the “haves” who thrive in 1988 America. Actual humans are stand-ins for the “have nots.”

Predicting internet memes

Carpenter, using the pseudonym Frank Armitage, pads out Ray Nelson’s 1963 short story “Eight O’Clock in the Morning” into a 94-minute film that’s categorically both SF and horror, but more of the former. It sits at the cultural midway point between “The Twilight Zone” and internet memes.

The film builds too slowly, although we do get a good sense of what it’s like to be a homeless drifter. The pace picks up in the second act when Nada finds sunglasses – produced by a resistance group — that allow him to see through the veil to the Philip K. Dickian black-and-white reality that exists beneath.

In addition to seeing the zombie-aliens’ true faces, he sees that advertisements and magazines convey simple messages at their root: “obey,” “stay asleep,” “no thought” and “marry and reproduce.”

In the action-oriented final act, Nada and his new ally Frank (Keith David, “The Thing”) aim to take out the device that beams these messages into people’s minds; it sits atop a Los Angeles TV station.

But the film is mostly about the frustration of a revolutionary trying to get people to see what’s really going on. As Harriet Tubman said, she could’ve freed many more slaves if they knew they were slaves.

Longest alley fight ever

“They Live’s” core theme is ironically illustrated in a sequence that also shows how padded it is: John and Frank’s alley fight – although nicely choreographed (Piper is a pro wrestler) — plays like Peter Griffin fighting the chicken on “Family Guy.” It goes on forever, and the reason for the fight is bizarrely simple: John wants Frank to put on the glasses.

Early in the film, the duo are fairly upbeat about their horrible circumstances. They are homeless and they’ve left their hometowns to find construction work in L.A.; Nada left nothing behind in Denver, whereas Frank has a wife and kid in Detroit.

As one of the aliens – a stand-in for Reagan – says in a TV broadcast, it’s “morning in America,” and John believes in the American dream despite his current hard times. Folks at the homeless camp are friendly and welcoming, at least.

But then the police bulldoze the Reaganville camp and round up the homeless people and shoot them. This isn’t all that different from how homeless people are treated in reality, except that they usually aren’t murdered. Perhaps it would be kinder to them – and better achieve the government’s aims – if they were.

Surprisingly, “They Live” doesn’t have an overt governmental presence – unless you count local police following off-screen orders. Much like “The Ganymede Takeover,” the 1967 novel Nelson co-wrote with Dick, this society features a buffer zone of human leaders between the alien rulers and the working-class rabble.

Transition is possible

“They Live” shows the transition from a “have-not” to a “have” is possible, if you can avoid being murdered. (Presumably the state’s wiping out of the homeless is an aesthetic consideration, since valuable labor comes from such camps.)

The construction site’s foreman makes it into the secret elite group – it holds ritzy galas underground — which increases everyone’s wealth and welcomes new members.

A viewer gets the sense that Nada’s belief in the American dream is not entirely misplaced in regard to this socio-economic structure. If you can get above that bottom rung, the world of “They Live” is quite nice.

The home of preppie Holly (Meg Foster, giving a perfectly flat “Twilight Zone”-esque turn) is wonderful 1980s comfort. The film has lots of images of shopping that are nostalgic today, when that activity has largely moved online.

The film operates best as a critique of the way the “haves’ ” success comes about. Holly works at the TV station, and it’s debatable in the real world if local news is “the enemy,” but it is in this film’s world.

A hint of cli-fi

In “They Live,” TV news is a mouthpiece for oligarchy (what we have in modern America) – corporations maintaining success via political arrangements rather than honest capitalism.

That’s not to say that if the aliens stop killing homeless people and instead let them into the club that this would become a perfect socio-governmental system. There’s another wrinkle, important for allowing this film’s conflict to click: The aliens seek climate change so the Earth environment becomes more comfortable for them.

In the long term, they are not cooperating with humans, they are tricking them. In the real world, governments’ artificial handcuffing of worldwide progress does hurt the environment (as poor countries stay in the coal era longer than they otherwise might), but most politicians are ignorant of this process.

As with the similarly themed “Halloween III: Season of the Witch” (1982), on which Carpenter is an uncredited writer, “They Live” has plenty of room for interpretation and discussion – and that is its strong point. Strictly as a piece of filmmaking, the slow pace hurts it, and it’s not the ideal Carpenter film if you want visceral horror.

But it’s still an important entry in the catalog of a genre master, with themes (or at least memes) that unfortunately prove timeless.