We can often see a progression in Woody Allen’s catalog where something that’s a small point in one movie becomes a central point in a later film. Such is the case with “Cassandra’s Dream” (2007), the third of Allen’s London trio from 2005-07.

The internal cost

“Match Point” (2005), one of his masterpieces, touches on the inner psychological price of committing a murder. But the film’s structure is such that Allen can’t dig too deeply into it.

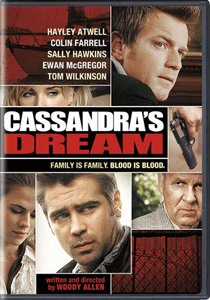

“Cassandra’s Dream” is his platform for that dig. Brothers Ian and Terry (on-their-game Ewan McGregor and Colin Farrell) are approached to commit a murder, and they think about the pros (which are measurable) and cons (which are moral and psychological).

“Cassandra’s Dream” (2008)

Director: Woody Allen

Writer: Woody Allen

Stars: Ewan McGregor, Colin Farrell, Hayley Atwell

The movie benefits hugely from the Philip Glass score that always indicates this is a mood piece. I’ve seen it wrongly described as a dark comedy, perhaps because Allen makes so many comedies, including some about murder.

To be fair, it’s close to that genre. In many scenes, especially early, one almost wants to laugh, as if we’ve been trained to do so. There’s something morbidly amusing about Terry’s gambling addiction and Ian’s ceaseless dream for a brighter future.

But after enough scenes without a punchline, we realize Ian could have a brighter future with his new girlfriend (“Agent Carter’s” Haylely Atwell as Angela), and also that Terry’s is a serious thread about gambling troubles.

Terry also has troubles with drugs and smoking and drinking – and actually thinking, in a way. Allen contrasts the two brothers’ reactions – especially outwardly – to the idea of murder. Terry openly acknowledges what Ian is keeping bottled up: that murder is “crossing a line.”

A quick bit of dialog from Ian tells us where that “line” comes from: “We’ve been raised to know right from wrong.” Although Allen is often interested in religion, Terry peppers “God” into his arguments only a couple times, and in an abstract sense. “Cassandra’s Dream” can be enjoyed by anyone with a sense of right and wrong, regardless of the source of that sense.

Old-fashioned style

Of course, Allen is not the first filmmaker to dive into the way murder has a price even if you pull it off without getting caught. In a subtle way, he admits to the film’s place in a grand tradition. The film may be set in contemporary London, but many cues paint it as old-fashioned.

The main reason, ironically, is Glass’ score. It’s a rare case where Allen uses newly composed music rather than interstitial tunes from old jazz records. Glass taps into the mood of old thrillers such as those of Hitchcock. Scenes are paced a tad slower than in Allen’s comedies, allowing room for Glass to work.

Ian drives a vintage car – which he borrows from Terry’s auto shop, the customer being none the wiser – and Allen spends some time with him on a wooded country road. This is where Ian meets beautiful stage actress Angela, helping her with her stalled car.

Another old-fashioned touch – which is admittedly common in Allen films – is that he shies away from actual moments of violence. A gun is pulled, the camera pans into the nearby bushes, and we hear the shot. It’s a low-caliber gun, like in old movies.

In this way, “Cassandra” lingers in an abstract zone wherein we know murder is nasty business but we don’t have to see it. Old movies, because of the sensibilities of the time, ask us to go with it, and so does Allen. I was willing to, although it’s interesting to think how a corpse might’ve changed the tone.

Contrasting reactions

“Cassandra’s Dream” has a similar issue to Allen’s second U.K. film, “Scoop” (2006), in that it’s repetitive. But it’s less extreme here. In “Scoop,” the debate about whether Hugh Jackman’s character is a serial killer continues until the story has reached movie length.

In “Cassandra,” the moral debate and the differing effects on the brothers has forward movement, even if we’re encouraged to mull things over. And the fact that this is a serious piece allows us to appreciate McGregor and Farrell, who truly seem like brothers.

The film ultimately has leftover parts, such as Atwell as the seeming femme fatale (to continue the old-school theme) who really isn’t. But while McGregor and Farrell are the main course, the garnishes are flavorful.

Also in strong supporting turns are Sally Hawkins as Terry’s wife; she’d later play another – though differently accented – supportive spouse in “Blue Jasmine.” And when the great Tom Wilkinson enters as the brothers’ uncle, “Cassandra” takes its dark turn and kicks into gear.

Not about the plot details

The uncle’s situation might be a sticking point for some people who dislike this film (which ranks low on many rankings of Allen’s filmography).

The details of what dirt his corporate colleague has on him are never explained. This is because they aren’t relevant to the reason the film is being made: to explore the spiraling psychological ramifications of murder.

I’ve run into this debate in 2021 regarding “The Little Things” and “Those Who Wish Me Dead,” two more films where some plot specifics are not present in the screenplay because they aren’t the point. If a viewer really gets interested in the uncle’s situation, they will feel ripped off.

I’m not sure what the solution is. It might be inevitable that some people will want a different film than what they’re given.

For me, Allen has proven himself enough times that I’m willing to go on the ride he chooses. With a dash of style and a fair amount of substance, “Cassandra’s Dream” is one worth taking.