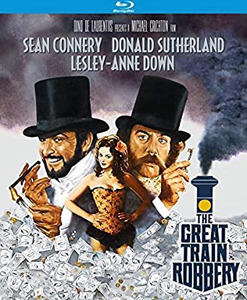

Writer-director Michael Crichton turns around his 1975 novel “The Great Train Robbery” for a 1978 film that reaffirms his technical competence but lacks flair. It’s a very faithful adaptation of the book. The main sacrifice is the rhythm of the language. Although Donald Sutherland’s “screwsman” (key copier) Agar uses a lot of the 1850s words, it sounds like the actor is performing a part. The book – loosely based on a real event — swept me into that time more.

Faithful adaptation

Still, Crichton gets a lot of the book in here. When “snakesman” (like the world’s greatest parkour artist combined with Tooms from the “X-Files”) Clean Willy (Wayne Sleep) scurries through the London slums, we peek into the squalor. We get a glimpse of a guy sleeping on ropes strung between two walls – one of the historical novel’s most surprising details.

Charisma-dripping Sean Connery and beautiful Lesley-Anne Down carry us from scene to scene as Pierce and Miriam. When we meet these professional thieves in a hotel room, Connery is wearing a sheet and eating grapes while Down slips out of her 19th century attire in a multi-stage striptease. As we also see with the long-johns-wearing men, clothing of this time consisted of many layers.

“The Great Train Robbery” (1978)

Director: Michael Crichton

Writer: Michael Crichton

Stars: Sean Connery, Donald Sutherland, Lesley-Anne Down

Malcolm Terris’ supporting turn as a ruling-class man, Fowler, adds color. Fowler almost gets it on with Miriam – once consensually (as part of the scheme), once not. The character illustrates the class difference of this time. Times are changing, though. Women’s suffrage is in the air, even if it’s literally laughable to the elite.

One opportunity for big humor is missed. Connery dates a plain woman in order to gain access to a key. It’s presented matter-of-factly even though the visual pairing of the world’s sexiest man and the drab woman calls out for laughs.

On the robber’s side

From that first shot of Connery, “Train Robbery” has us on Pierce’s side even though he’s a robber. Indeed, the gallery’s joyful response to his courtroom zinger (“I wanted the money”) affirms that he’s a hero of the people. Even though they cheer the hanging of a prisoner earlier in the film, Connery’s honesty makes him popular.

Also, he’s stealing from the British Empire’s war chest. Even in the 19th century, maybe there was some anti-war sentiment.

As with the book, the film – called “The First Great Train Robbery” in foreign releases – is a procedural. If you don’t get enjoyment from watching an hour of steps before the titular grand finale, this isn’t the film for you.

But the details are smart. Compare this movie to the recent “Army of Thieves,” for instance. In that film, the safecracker succeeds three times by listening really closely. In “Train Robbery,” we avoid that redundancy.

(Well, there is one odd redundancy. The safe carrying the gold requires four keys, but they come in two identical pairs. Granted, the thieves didn’t know that ahead of time, so they didn’t know they could save time on the copying. But it’s a strange bit of corner-cutting by those on the security side.)

An early impossible mission

Two action sequences are remarkable for their stunt work. In one, Clean Willy scales a prison wall on both sides. In the other, Pierce crawls atop a fast-moving train to get from one compartment to another – 18 years before Tom Cruise in “Mission: Impossible.”

In “Travels” (1988), Crichton writes about filming this sequence. The filmmakers miscalculated and the train was moving faster than they thought; Connery was in actual danger. Also, the actor told Crichton that they had enough footage, forcing him to nix the last day of shooting. The director later realized Connery’s call was correct.

And I concur; the sequence isn’t missing anything. In fact, it’s on the show-offy side. Yet something is missed. Pierce is covered in soot according to the dialog, but in actuality he is not.

Meanwhile, Sutherland is amusingly made up like a corpse as part of the scheme. “The Great Train Robbery” isn’t a cheap-looking film (Crichton was rightly known for getting bang for his buck), but I noticed the corner-cutting.

The novel is better, but this adaptation is faithful and will be enjoyable to fans of the book. (Those who dislike the book – it is one of Crichton’s most divisive works – should skip the film.) Perhaps inevitably, the movie is less insightful than the book and more of a plain ole adventure.