In “Melinda and Melinda” (2004), Woody Allen posits there’s a thin line between comedy and tragedy, then successfully proves it. A group of writer friends at a restaurant starts with a real-life situation one of them encountered: A woman named Melinda (Radha Mitchell) pops in unannounced at a dinner party. Wallace Shawn (recalling “My Dinner with Andre”) spins a comedic tale from this, while Larry Pine spins a tragedy.

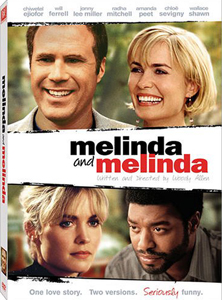

A tale of 2 Melindas

What’s less clear is whether this makes for a striking movie. I found it to be a good movie, at least, in the sense that I was engaged in the stories of Mitchell’s two Melindas. In the tragedy, she committed adultery and will never see her two children again. In the comedy, her husband cheated on her, they had never had kids, and now she’s newly single.

As you can tell from those descriptions, Melinda’s initial situation is either tragic or not. Going into the film, I had thought Allen would screen similar scenes back to back, showing the slight push that makes it either tragic or funny.

“Melinda and Melinda” (2004)

Director: Woody Allen

Writer: Woody Allen

Stars: Radha Mitchell, Will Ferrell, Chloe Sevigny

That’s not what “Melinda and Melinda” is. Maybe that would’ve been too easy. Maybe it would’ve been too repetitive.

As it stands, Comedic Melinda is in the ballpark of Annie Hall – flighty and endearing, with men easily falling in love with her. Will Ferrell ably plays the Woody Allen Character, with droll one-line observations about the human condition.

He’s married to work-obsessed Amanda Peet but loves apartment neighbor Melinda. Humorous romantic musical chairs ensue, especially when Ferrell finds Peet in bed with another man and enthusiastically nods when she suggests they should get a divorce. After all, this frees him to pursue Melinda.

A fine line: Allen Tragedy vs. Allen Comedy

Tragic Melinda, meanwhile, leans toward Jasmine of the later “Blue Jasmine.” She has a lot going for her but is not wired for success; indeed, she is suicidal. She meets suave pianist Chiwetel Ejiofor, but soon ends up in a love triangle that includes her longtime bestie, Chloe Sevigny.

So we have two distinct storylines, with the common elements being 1, the starting point of a surprise pop-in, and 2, Mitchell playing Melinda (although they aren’t the same Melinda).

Despite its unusual structure, “Melinda and Melinda” doesn’t provide eye-opening observations. But the more I think about it, the film is making more subtle comments. Firstly, Allen is commenting about storytelling.

If there’s a fine line between tragedies and comedies, there’s an even finer line between Allen’s tragedies and Allen’s comedies. This is because his tragedies usually include spices of comedy, and his comedies always include spices of tragedy.

Indeed, I used a trick to keep the two stories straight in my head: Ferrell (who I associate with comedies) is in the comedy part, while Sevigny (who I associate with edgy indies) is in the tragedy part.

A mature, but incomplete, statement

Secondly, Allen might be saying happy people draw good fortune their way while morose people draw bad breaks. Although not a supernatural film like some of Allen’s works, “Melinda and Melinda” does playfully reference higher powers, ranging from a genie’s lamp to God.

Comedic Melinda follows her heart through twists and turns and ends up happy. Not only that, things work out perfectly for Ferrell and for Peet and her new lover, too. Tragic Melinda is neurotic, dwelling on how a relationship will turn sour before she even meets a guy her friends are setting her up with.

It’s like Allen – at least in this film — is saying people create their own luck with the vibe they send into the universe. That’s a mildly surprising statement from him, because I think of him as leaning cynical.

On the other hand, it’s a mature statement — and his films, while idiosyncratic, are mature in their honesty. It foregrounds personal responsibility and backgrounds random chance. I think both types of energy exist, but we can only control one of them.

So – if you can manage it – be positive and control what you can control. But the weird thing is that each of the Melindas is wired one way or another and the film doesn’t present much of an escape path for the troubled one. Maybe this shortcoming percolated in Allen’s brain and eventually led to the deeper masterpiece “Blue Jasmine.”

Life is beautiful when candlelit

“Melinda and Melinda” didn’t totally grab me with its premise (while watching it), but I did take to it on basic filmmaking grounds. “Comedic Melinda” is an enjoyably mild rom-com, and “Tragic Melinda” is an accessible statement about depression.

Highlighting both versions are candlelit scenes in a French bistro – with Vilmos Zsigmond at the lens, in the first of three Allen collaborations (“Cassandra’s Dream,” “You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger”). Interestingly, “Tragic Melinda’s” scene has everyone high on wine and love, while “Comedic Melinda’s” scene gives the heady falling-in-love experience to Melinda but not to the Allen Character, Ferrell.

The interspersing of the two short films didn’t bother me, but I’m curious to know the experience of watching each of them as 45-minute standalones. Maybe a better film would’ve resulted if I was bothered by the back-and-forth. What if “Comedic Melinda” played up bright lighting and jaunty tunes, while “Tragic Melinda” played up dim lighting and a somber score?

That would’ve been a different project, and even describing it, I imagine it would be blunter. Allen’s actual film is more subtle, and I suspect it’s saying some things I haven’t thought of in the wake of my viewing. Because of Allen’s track record, I trust that “Melinda and Melinda” says what he wants it to say, and I wouldn’t mind hearing more interpretations of it.