“Night of the Living Dead” (1968) is a little bit of homework, a little bit of entertainment. It’s artistic but slow enough that you dwell on the artistry more so than getting swept away by the story. But it’s obvious in every beat that director/co-writer George Romero has launched a new horror subgenre: the modern zombie film.

Four decades later, “The Walking Dead” would take this story template and add new details of zombie lore, enriching the post-apocalyptic experience without fundamentally altering what Romero started.

Something old, something new

Even though “Living Dead” ushers in something new, it’s a stylistic throwback, with Romero de-emphasizing his weaknesses. Like Hitchcock’s purposefully old-school “Psycho” (1960), this film is in black-and-white with deliberate pacing. Sixties viewers recognized it as a throwback; today’s viewers might mistakenly believe this was still the style in 1968.

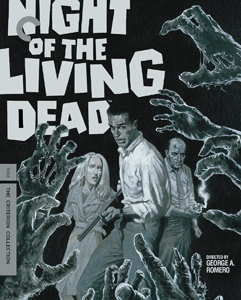

“Night of the Living Dead” (1968)

Director: George A. Romero

Writers: John A. Russo, George A. Romero

Stars: Duane Jones, Judith O’Dea, Karl Hardman

Although the film uses stock music from a dozen composers, it’s driven by the score, like a silent film, in all of its action sequences. The first of these finds Barbra (Judith O’Dea) running in terror from a zombie, from the cemetery to a farmhouse, after her brother becomes its first victim.

Later, we get talky, stagey sequences. Ben (Duane Jones), who takes charge of the survivors in the farmhouse, argues tactics with Harry (Karl Hardman), who would rather vault himself and his family in the basement.

It seems Romero, at this early point in his career, can’t do action and dialog at the same time. But it’s almost a style perk rather than a bug. It’s as if he’s retroactively adding “zombie” to the roster of Universal Monsters, creating a 1928 film in 1968. (It could be argued that Frankenstein’s Monster is himself a zombie, but that’s a discussion for another time.)

They’re coming to get you … but stay calm and carry on

Hurting the tension, there’s a disconnect between the supposed threat and the fact that these zombies are slow-moving. (Slow-moving zombies are often called “Romero zombies” in horror parlance.) Every time Ben emerges from the house to light something on fire in front of the porch, the threat level seems very low.

The up-close zombie attacks make one wonder if there was a stunt choreographer on the set. And every time something is lit on fire, I think of the high percentage of the budget going up in flames on that shot. Remarkably, considering the subgenre’s eventual status as a home for makeup-effects artists, very little of the budget goes to makeup or prosthetics. However, the actors’ zombie movements are in place from the beginning, only with moments of deliberate intelligence that are now rare – like when zombies purposely destroy the truck’s headlights.

Despite the zombies’ slowness, disaster-film tension comes through when the farmhouse survivors listen to the radio and TV. Viewed today, “Living Dead” is striking and refreshing for how the newspeople simply report the facts and give listeners the information they need.

The TV screen lists government shelters as the anchorman advises people to try to reach the nearest one. As information comes in on the nature of the ghouls and how to kill them – destroying the brain, or burning them – the reporters rather calmly present it.

The question of how the zombies came about is touched upon – radiation from Venus – but there’s absolutely no unfounded speculation by pundits. The government officials are reasonably open with their knowledge, and no one plays the blame game. It was a different, and perhaps better, time.

Some surprises

A more deliberate commentary on 1968 comes via the fact that Ben is a black man. This was within the same decade when federal written law began to be interested in treating citizens equally, regardless of race. However, “Living Dead” doesn’t verbally address racism in survival situations even once; it’s simply there if a viewer wants it.

Capping off this 96-minute exercise is perhaps the most nonchalant tragic ending of all time.

Throw in behind-the-scenes weirdness – namely the post-production team’s mistake of not putting the copyright notice in the titles, thus putting the film into public domain and costing Romero a fortune – and this film is a fascinating intellectual chapter in film history.

“Night of the Living Dead” is a mildly entertaining viewing experience independent of its context, but of course it can’t be viewed that way anymore. I imagine some film historians find it wrong to watch a certified classic as if it’s a non-contextualized piece of entertainment, and call it merely OK.

But I’m glad I watched it, as I’m now primed to see what happens next as Romero’s saga becomes colorized and contemporary in the sequels.