Director Alan J. Pakula delivered the three podium holders of dark Seventies noir, starting with “Klute” (1971) before adding the slightly more famous “The Parallax View” (1974) and the much more famous “All the President’s Men” (1976).

I first learned about Pakula’s work from an “X-Files” reference book (Jan Delasara’s “PopLit, PopCult and ‘The X-Files’: A Critical Exploration,” from 2000) noting the show’s influences, and I can see those influences in the first entry of the director’s “paranoia trilogy,” but in a different way than I expected.

Pakula’s breakthrough

I often think of Seventies noir as focusing on government corruption and corporatism. But “Klute’s” plot is a simple throwback – a search for a missing man that goes into gorgeously grim corners of New York City and human psychology, not the inherent evils of the state and those with connections.

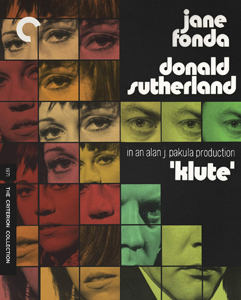

“Klute” (1971)

Director: Alan J. Pakula

Writers: Andy Lewis, David E. Lewis

Stars: Jane Fonda, Donald Sutherland, Charles Cioffi

Over three days, RFMC is looking back at the masterful and influential “paranoia trilogy” – “Klute” (1971), “The Parallax View” (1974) and “All the President’s Men” (1976).

A rural man named Tom Gruneman (Robert Milli) disappears, and the only clue is letters he sent to a prostitute in the city, Bree (Jane Fonda). Gruneman’s private-investigator friend John Klute (Donald Sutherland) – one of those wonderfully bitten-off names in the vein of John Wick – starts with that lone lead, tracking down Bree and her cold shoulder.

Sometimes movies benefit from the viewer not knowing what they’re in for. IMDb lists “Klute” as crime, mystery and thriller, but it’s really in the romance genre. It’s an organic exploration of how Bree grows attached to Klute for the safety and trust he provides – traits that she doesn’t know how to deal with, as we learn from the cutaways to Bree’s therapy sessions.

The performances are all over the place, on purpose. Pakula – maximizing a straightforward screenplay by TV veteran brothers Andy and David E. Lewis – has Fonda (rightly the Oscars’ Best Actress winner) give a big, human performance. Those therapy sessions are the stand-in for traditional noir voiceovers.

She’s acting against a brick wall in Sutherland, but that’s just who Klute is. He’s not outwardly expressive. Even his investigative methods are rote, rather than inspired. He doesn’t give hardboiled voiceovers. It’s ironic that the movie is called “Klute” rather than “Bree,” yet he’s very much a person, and we can see why Bree is magnetically attracted to him.

NYC’s netherworlds

Then we meet the villain (I won’t reveal the person because this is a mystery), and the actor gives a performance like those “X-Files” baddies whose evil is found in the netherworlds of psychology – chilling for the surface normalcy.

The NYC backdrop is unquestionably an additional star, and Pakula, cinematographer Gordon Willis and the location scouters maximize it. As Michael Small’s weirdly tinkly yet somehow effective score plays over it, we revel in the grimy, unsafe but definitely alive city.

Standout locations include Bree’s studio apartment – everything visible in one shot, and always slightly lit because Bree fears total darkness – and Klute’s contrasting hovel in the basement of the same building, which he acquires to tap her phone calls. (The spying tech does move noir into a new era, even if the plot is old-school.)

In a tasty sequence, Klute investigates noises on the roof and explores a condemned area of the building. In this instance, it’s a false alarm – the noise was young, stoned-out squatters in a blocked-off apartment.

Purely as a plot, “Klute” is slow-moving with false leads. But plot is not the point; it’s about the feelings you get while following the plot. And yet the Bree-Klute relationship resonates with me as much as the delicious look and feel. Heck, this is one of the truest portrayals of two people being drawn together that I’ve ever seen, and it’s not even why “Klute” is cited as a touchstone in noir history.

Typewriter image by Markus Winkler from Pixabay