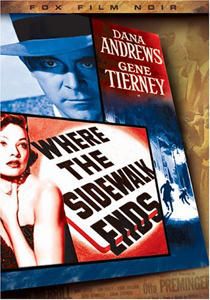

Six years after the lauded “Laura,” the trio of director Otto Preminger and stars Dana Andrews (the guy) and Gene Tierney (the dame) reteam for “Where the Sidewalk Ends” (1950). This noir isn’t as well-regarded, despite having more front-facing performances and a quite good premise. It’s hurt in the end by a plot hole that I suspect might’ve been inflicted by the Hayes Code.

And where the hell was he?

There’s no arguing with the screenplay’s pedigree, or most of its content. It comes from Ben Hecht, responsible for what many say is the most noir-ish Alfred Hitchcock film, “Notorious” (1944). He works from the adaptation of three writers, who themselves adapt the William L. Stuart novel “Night Cry” (1948).

“Where the Sidewalk Ends” is a more evocative title, making me think of Frank Drebin narrating “And where the hell was I?” in “The Naked Gun.” But it’s actually metaphorical, describing the inner journey of police detective Mark Dixon (Andrews), who – as we learn oddly late in the film – has thievery in his family background. He intends to take the family tree on a more noble branch.

“Where the Sidewalk Ends” (1950)

Director: Otto Preminger

Writers: Ben Hecht (screenplay); Victor Trivas, Frank P. Rosenberg, Robert E. Kent (adaptation); William L. Stuart (novel)

Stars: Dana Andrews, Gene Tierney, Gary Merrill

Andrews is suave and above-it-all in “Laura,” but here he brings some trouble to his expressions, despite still fitting firmly into the hardboiled style. Tierney morphs from “Laura’s” objectified cypher into the down-to-earth Morgan Taylor, who lives with her blue-collar dad Jiggs (Tom Tully) as she tries to find a career.

After a straightforward opening where we learn Mark is a promising detective with a hot temper, and where we meet mob boss Tommy Scalise (Gary Merrill, a perfect mix of calmness and slime) at a dice table, Hecht’s screenplay does a Reverse Hitchcock.

(SPOILERS FOLLOW.)

The cover-up (Spoilers)

In many Hitchcock films, we follow an innocent man navigating a plot, hoping to be a free man at the end. In “Sidewalk,” we follow a guilty man navigating a plot, hoping to reach a palatable end. It’s equally gripping.

We like Mark well enough because he’s the main character, but the staging of a pivotal scene also makes it clear that he kills Ken Paine (Craig Stevens), a hanger-on to Scalise and estranged husband to Morgan, in self-defense and by accident. But because he’s on thin ice at the precinct, Mark decides to cover it up rather than come clean.

“Laura” either suffers or is enhanced by the fact that we don’t know anyone’s inner motivations, but in “Sidewalk” we’re walking hand-in-hand with Mark. We know him well enough to know he won’t let Jiggs (in the wrong place at the wrong time) take the rap, but we don’t know how he’ll pull it off. And we know Morgan likes him, but he is racking up quite a list of things to be forgiven for.

The tension remains high, but the ending is undercut by a plot hole that I think might’ve been created by the Hayes Code’s guidelines about bad guys being caught and good guys having happy endings. An early scene shows that Mr. Morrison – the murder victim the initial mystery (such as it is) spins from – was down $1,900 to Scalise. Later, some people say he was up $1,900. If he was down, the mob boss would not want to kill him; if he was up, he might want to kill him.

The way things are conveniently cleared in the closing scenes gets the motivations mixed up. Or else I read the whole thing wrong.

(END OF SPOILERS.)

This time, characters outstrip mystery

At any rate, as a whodunit in the death of Morrison (who has so little screen time there’s no credited actor), “Sidewalk” is borderline unsolvable. Or maybe it’s supposed to be so obviously solvable that it’s not even a whodunit, and I just misinterpreted the information.

The plot then focuses on the death of Paine, and we know what happened there, so that’s a howcatchem from the reverse angle; we’re rooting for the killer to – if not necessarily get off – navigate the situation as best he can.

Because of this engrossing premise – and performances by the two leads that show their range much more than “Laura” (which is a much better mystery, granted) – “Where the Sidewalk Ends” is a noir worth watching. But you might be thinking about some plot points for reasons the filmmakers didn’t intend.