“Stage Fright” (1950) revisits the wrongly pursued person and theatrical setting of “Murder!” (1930) and executes the subsequent events better. Flirting with slow-burn romantic intrigue as much as it is a suspenser, this adaptation of Selwyn Jepson’s 1947 short story “Man Running” also includes one of the most controversial structural components in Alfred Hitchcock’s catalog: a flashback that doesn’t play fair with the audience.

Another murder!

More on that later. The best part of “Stage Fright” – which has fewer theater scenes and scares than I might’ve liked (although more of both than “Murder!”) – is the relationships. Jonathan Cooper (Richard Todd) is in love with a married woman, the actress Charlotte Inwood (Marlene Dietrich, earning her ice queen reputation here).

She asks him for help, but that gets him in trouble. He asks longtime friend Eve Gill (Jane Wyman) for help, but that gets her in trouble. She asks a new friend, the detective Wilfred Smith (Michael Wilding) for help, and that gets him … well, not in trouble, but confused.

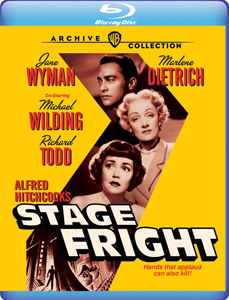

“Stage Fright” (1950)

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Writers: Whitfield Cook (screenplay), Alma Reville (adaptation), Selwyn Jepson (short story)

Stars: Marlene Dietrich, Jane Wyman, Richard Todd

The story by Whitfield Cook and Alma Reville is complex, but due to being totally linear (except for one flashback near the start), it’s not confusing. This allows us to soak up the theme of people being in love with someone who doesn’t love them back, and some people taking advantage of that. Though we focus on merely a love rectangle, “Stage Fright” posits an endless cycle of people breaking each other’s hearts, and their own.

One could argue it’s at least a love pentagon, if we include the victim we never get to know except as a corpse – the husband of Charlotte. Heck, it could’ve become a love hexagon if the detective had eyes for anyone other than Eve. Patricia Hitchcock’s carnival-flier distributor Chubby just doesn’t do it for him.

Framing the action

“Stage Fright” is a good but sleepy film, with lots of low-grade suspense, but no big set pieces until the climactic early example of the use of recording equipment to get a confession for the sake of evidence. Hitchcock and company pepper humor throughout the series of low-key back-stabbings, but it never quite meshes, even though the sense of lightness is welcome.

Alastair Sim provides a lot of the bemused tone as Eve’s father, who lets Eve talk him into harboring Cooper, the classic Wrongfully Accused Man. In this case, he’s the victim of Charlotte’s frame job rather than the standard Hitchcockian misunderstanding. The narrative features Eve (with input from her dad and Cooper) trying to return the frame to the actual killer, Charlotte.

Eve poses as Charlotte’s maid “Doris” for a while, and in one carefully structured segment, Wyman has to play both Eve and “Doris” at a carnival, depending on who she’s interacting with. The goofy guffaws of something like Amanda Bynes’ “She’s the Man” don’t exactly follow, as Wyman plays it all with caution and concern.

Maybe that’s why Hitch peppers humor into the margins, like Charlotte calling “Doris” every typical maid name except Doris. Other mild screwball humor comes from the relationship between Doris’ parents, who have become comfortable sleeping in different rooms. When they agree to harbor Cooper, Cooper will take Eve’s room, Eve will take the couch … and Mrs. Gill then wonders where Mr. Gill will sleep.

Also providing a diversion is Charlotte performing Cole Porter’s “The Laziest Gal in Town.” It’s an appropriate number, because her frame job is rather lazy. She has given a bloodstained dress to Cooper, thus allowing the possibility of a reverse frame-job. And also, the screenplay is lazy in one controversial but fascinating aspect.

Telling tales (Spoilers)

(SPOILERS FOLLOW.)

At “Stage Fright’s” start, Cooper explains to Eve what happened, and we the viewer see the events in flashback. The bloodstained Charlotte asks Cooper to grab a new dress for her from her house, the murder scene. He goes there and grabs the dress, but maid Nellie (Kay Walsh) spots him as he runs off. Thus he now needs Eve to help him hide.

In the finale, we learn that flashback did not happen, at least not precisely like that. It turns out Cooper killed Charlotte’s husband, spurred on by her. Some folks working on the film were uncomfortable with the dishonesty of the storytelling, but Hitch vetoed them.

The film as it stands is not offensively dishonest, as unreliable narrators are of course allowed in cinematic storytelling. But this tool must be used cautiously, and I think there were better options. Cooper could’ve told this story to Eve as a simple narrative, without the visuals.

An even better solution – more challenging, but it would fit with “Stage Fright’s” convolutions – would be to show the part of Cooper’s story that’s true but leave the false parts as a pure narrative from Cooper. With careful rewriting, the filmmakers could’ve retained the truth of Cooper being the murder and also the truth of Charlotte manipulating him, thus retaining the themes and plot while playing totally fair.

“Stage Fright” (rather surprisingly) hasn’t been remade; if it is, it would be neat to see if the writers could pull off the same story without a dishonest presentation. I think they could. But if we are stuck with Hitchcock’s version of “Stage Fright,” that’s nothing to complain too loudly about.

RFMC’s Alfred Hitchcock series reviews works by the Master of Suspense, plus remakes and source material. Click here to visit our Hitchcock Zone.