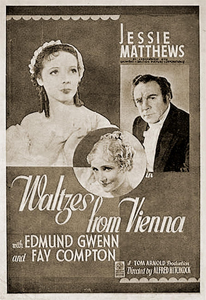

“Waltzes from Vienna” (1934) isn’t quite a musical – after all, it focuses entirely on the creation of a single song, Johann Strauss II’s “The Blue Danube Waltz” (1866). But it’s an important transitional film for Alfred Hitchcock, whose six talkies before this were either staid stage adaptations or took intriguing lurches toward his eventual cinematic flair.

Transitional techniques

I hope to learn more about the filmmaking techniques someday, but from this viewing, “Waltzes” seems to be a mix of primitive and modern. In early talkies, the celluloid recorded both image and sound; they couldn’t be separated. Therefore if the film was cut mid-sound, it would result in a loud pop. As such, directors tried to end every scene in dead silence.

Some sequences in “Waltzes” play like that. But others are in the modern style, cutting to different angles and points of view; for example, the semi-farcical but well-staged fire sequence at the start, wherein restaurant workers and patrons clear out and set up again in the street. Background music helps the action to flow smoothly; was this added later, as it was for the “Hitchcock 9” silent films?

“Waltzes from Vienna” (1934)

Also known as: “Strauss’ Great Waltz”

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Writers: Guy Bolton, Alma Reville (screenplay); Heinz Reichert, A.M. Willner, Ernst Marischka (stage play)

Stars: Edmund Gwenn, Esmond Knight, Jessie Matthews

At any rate, “Waltzes” moves Hitchcock closer to modern times, leading to that same year’s “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” considered by many to be his first really strong talkie. (I’d give the nod to the next year’s “The 39 Steps” as the step forward, and to 1940’s “Rebecca” as his first masterpiece.)

Speaking of filmmaking qualities lost to the mists of time, “Waltzes” suffers from mediocre preservation. Thankfully, it has viewable picture and listenable sound, rather than being lost entirely. But it’s murky, at least in the versions I found on YouTube.

Actresses Jessie Matthews and Fay Compton are intended to look vibrantly lovely, especially in their dresses at the climactic fete premiere of “Blue Danube” by Strauss II (Esmond Knight), the young man they both admire, for subtly different reasons. “Waltzes” is driven by sight and sound, so it’s a shame it looks flat.

A sweet but tame biography

When writers Guy Bolton and Alma Reville – working from the 1930 play – try for comedy, they usually misfire. A sequence in the bakery is like a proto-“Shakespeare in Love,” as various baking rhythms supposedly inspire Strauss II in his writing of “Danube.” I admire the notion, though the execution is weak. But the film is only 76 minutes long in the versions I found on YouTube (and 80 minutes according to IMDb), so it never overstays its welcome in a given scene.

It’s not all style and missed gags. The love triangle has some heart and some conflict: Matthews’ Resi likes Strauss II for who he is, but – influenced by her baker father’s wishes – hopes he’ll go into baking. Compton’s married Countess Fay likes Strauss II for his music skill and enjoys collaborating with him; she writes the lyrics for “Danube.” Pulling the young man in yet another direction is his father, an established composing legend, played by Edmund Gwenn (“The Skin Game,” “The Trouble with Harry”).

If nothing else, we can point to “Waltzes” as the film where Hitch begins to understand the importance of music, a factor that will later elevate his best works. For a film that focuses on one song, it’s notable that “Danube” – which some viewers might recognize from “2001: A Space Odyssey” or commercials — doesn’t become an annoying earworm. And when we get to the grand finale, Hitch allows the orchestra to play the whole song. When folks twirl on the dance floor, it’s a more believable version of the sudden “Ninja Rap” phenomenon in “TMNT II: The Secret of the Ooze.”

Interestingly, Hitchcock himself felt that the buildup to the reveal of a song people already know was inherently undramatic. I think it plays fine, but I admit my engagement was enhanced by my hopes that Resi will understand that the countess is not a romantic rival and stay with Strauss II even if he’s a composer instead of a baker.

Unless a more luxurious print comes along, “Waltzes from Vienna” is a one-time watch. But it’s not as shameful an entry as Hitchcock thought. It’s certainly a pivotal one in the development of his technical toolbox.

RFMC’s Alfred Hitchcock series reviews works by the Master of Suspense, plus remakes and source material. Click here to visit our Hitchcock Zone.