Raymond Chandler himself said his contribution to the hardboiled genre was style. That’s evident in “The Big Sleep,” which some say has an incomprehensible plot, and “Farewell, My Lovely,” which is packed with quotable dialog and the author’s delicious similes and metaphors.

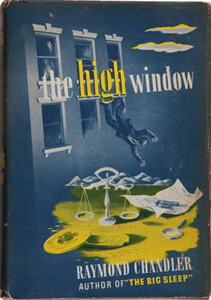

The style remains in “The High Window” (1942), but the plot and characters make a big leap. Granted, not many readers will solve this case; in fact, not many will view this as a puzzle mystery; we don’t come to Philip Marlowe novels for that specific pleasure. It is technically solvable, although if an Agatha Christie puzzle mystery has 500 pieces, “High Window” has 5,000.

Striking characters

The novel boasts a striking character, seemingly minor at first: Merle Davis, the secretary of Marlowe’s chain-smoking, dragon-lady client, Mrs. Murdock – one of the book’s many personalities that pop off the page. Rather than a femme fatale, Merle is a damsel in serious distress. That might be swapping one cliché for another, but Merle is a more believably drawn troubled young lady than Carmen in “The Big Sleep.”

“The High Window” (1942)

Author: Raymond Chandler

Series: Philip Marlowe No. 3

Genre: Hardboiled mystery

Setting: 1942, Los Angeles

Although the Forties was theoretically a rougher time for mental-health compassion than today, Marlowe – though often irked – does a remarkable job of recognizing Merle’s symptoms of unresolved past trauma and getting her some treatment. He’s even able to acquire a female nurse on call, since Merle’s specific trauma manifests as mistrust of men.

“The High Window” features fascinating clues. The Brasher Doubloon, stolen from Mrs. Murdock, is a maguffin, but Chandler turns this gold coin over many times to keep driving the plot. Among the twists: The doubloon is anonymously delivered to Marlowe at the same time the (seemingly) same doubloon returns to Mrs. Murdock’s possession.

As is becoming a pattern in the Marlowe novels, the nature of his assignment is not simply a matter of “Here’s the mystery, now work to solve it.” Rather, there are no murders at the start of the case (although there might be a mysterious death in the Murdock family’s past). One thing leads to another; Marlowe stays on the case partly because Mrs. Murdock begrudgingly extends his contract, and also because Marlowe has now stumbled across three corpses. He’s a person of interest of the police, understandably.

While the mysteriously disappearing and reappearing coin drives the plot, the clues come from human behavior. In addition to Merle, another fascinating one is George Anson Phillips, a green detective who tails Marlowe and asks to join forces. Chandler gives us the logistics of Marlowe moving about while knowing Phillips is tailing him, and also knowing that someone else is tailing Phillips. (Marlowe plays a one-sided chess game at home; appropriate, because this case ain’t checkers.)

Ground-pounding sunshine noir

The portrayal of the skill of tailing is a precursor to the modern Cormoran Strike novels by J.K. Rowling, which blend puzzle mysteries with detailed ground-pounding. Chandler also paves the way for Sue Grafton’s sunshine noir. Marlowe interviews a couple as they are lounging in the backyard. Meanwhile, a servant washes the car. I love the mix of information-gathering with a SoCal sunny day where the weather isn’t a concern.

It might seem incongruous, but the complexity of the overall plot – which at multiple points features innocent people taking credit for murders, further obfuscating things – makes the events seem more realistic, not less. This allows Chandler to set up the final conundrum for Chandler, involving detective-client privilege, which isn’t a legal thing, but it is a moral and professional concern.

As with Holmes and sometimes Poirot, Marlowe does not believe in the law as the be-all, end-all. It’s totally in bounds for him to know the identity of a killer and not share that information with the police. It’s not a moral issue for him, but rather a practical one. If the cops require him to share his knowledge, he will. But he’s not going to go out of his way.

“High Window” is great for understanding the intricacies of how private investigators and cops are sort-of allies, sort-of adversaries. And, considering the care with which he treats troubled Merle, the novel openly reveals Chandler’s open secret: For all of Marlowe’s superficial trappings as a cynical sleuth, he’s actually an old-fashioned knight.

A delight of sunny weather and grim happenings, “The High Window” is a great detective novel and a great novel, period.

Sleuthing Sunday reviews the works of Agatha Christie, along with other new and old classics of the mystery genre.