The mystery genre so exploded in popularity in the 20th century that the meta-mystery subgenre (movies poking fun at the tropes of mysteries) likewise exploded in popularity. So much so that Michael Caine is in “Sleuth” (1972), “Deathtrap” (1982) and the remake of “Sleuth” (2007). If someone told me he is in 1985’s “Clue,” I’d almost believe it, but he is not.

Caught in a meta trap

“Deathtrap,” which I’ll review here, has quite a pedigree across the board. Sidney Lumet, who made “The Verdict” the same year, directs. Jay Presson Allen (“Marnie”) writes the screenplay based on the stage play by Ira Levin, whose novels launched “Rosemary’s Baby” and “The Stepford Wives.”

The story plunges us right into the life of playwright Sidney Bruhl (Caine), searching for his next hit for one reason and one reason only: the money he’ll earn from it. Allen starts things off in a humorous alterna-world wherein plays, not movies, are the thing; Gene Shalit cameos with a pun-filled pan of Bruhl’s latest, “Murder Most Fair.”

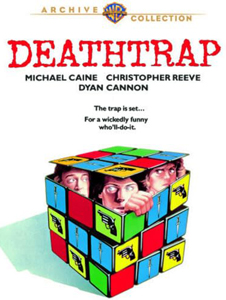

“Deathtrap” (1982)

Director: Sidney Lumet

Writers: Jay Presson Allen (screenplay), Ira Levin (play)

Stars: Michael Caine, Christopher Reeve, Dyan Cannon

Although the jabs at the industry don’t wane as “Deathtrap” progresses, the grimly gleeful slams of show-biz absurdities lag and feel like box-checking. We learn Bruhl had built up his career with a murder-mystery that just keeps going, a nod to the real-world equivalent, Agatha Christie’s UK hit “The Mousetrap” (and Levin’s “Deathtrap” itself, one of Broadway’s most ubiquitous plays). And “Murder Most Fair” plays on “Murder Most Foul,” a jokey, loathed-by-Christie adaptation of “Mrs. McGinty’s Dead.”

Alfred Hitchcock’s “Dial M for Murder,” arguably the best movie focusing on the plotting of a murder, gets name-dropped as Bruhl and collaborator Clifford Anderson (Christopher Reeve) write their intended hit play “Deathtrap,” about people collaborating together on a murder.

And the main character shares a first name with the director. That’s merely a lucky coincidence, since Levin wrote the play in 1979, before the movie was greenlit. Nonetheless: Whew. I wrongly thought the “Scream” films broke ground in taking meta to the breaking point and beyond, and maybe they have for slashers. But for murder-mysteries, Hollywood has long since gone into the weeds.

The anti-Superman

When we get deeper into the plot, though, “Deathtrap” – which is mostly set in Bruhl’s living room, and has several long shots, purposely making us feel like we’re watching a play – gets stuck in the weeds. Bruhl’s wife Myra (Dyan Cannon) is horrified that Sidney truly does seem desperate enough to kill Clifford and steal his script.

This stretch lacks the nuance we find in, say, “Dial M,” ultimately a deep study of human behavior wherein we’re fascinated by everyone in the small cast. Instead, it’s more of a marriage farce, but unfortunately not all that funny. A lot of the humor is broad comments on genre conveniences, such as the fact that Bruhl’s study (tucked at the back of the “stage”) features a wall of weapons. They are props from his plays, yes, but unquestionably the weapons will be used in this movie: Chekhov’s Wall of Guns (and More).

“Deathtrap” does feature a great mid-film twist in the vein of “For God’s sake, why didn’t I see that coming?!” That revelation has impact, as do other moments, but the stuff in between the sharp turns is decidedly blunter. Irene Worth comes in as psychic neighbor Helga Ten Dorp, and is asked to carry the movie for a while with comedy-via-personality; she gives a game effort, but it’s too much weight to lift.

Perhaps “Deathtrap” will be stumbled upon by people doing a dive into Reeve’s non-“Superman” stuff, an unfortunately shallow dive. He’s excellent here, never making me think of Superman. Except maybe in an opposite way, like he’s Bizarro-Superman. When Reeve flashes his trademark room-lighting-up grin as Clifford – who begins to absorb Bruhl’s lust for a hit play – it plays as sinister, not boyish.

Reeve was purposely trying for non-“Superman” hits himself, and never quite achieved it, but it wasn’t for lack of effort. The same goes for “Deathtrap.” The effort is here, and so is the cleverness; the laughs aren’t quite.