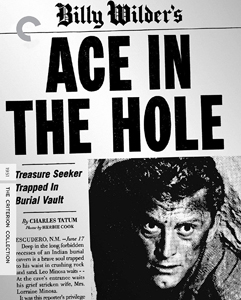

“Ace in the Hole” (1951) is a kind of silly, rather entertaining, certainly unusual piece in Billy Wilder’s catalog. Driven by a muscular, over-the-top performance by Kirk Douglas and featuring a rare outdoor, Western-esque setting, Wilder’s film has something to say about knowing where the line is when shooting for a quick buck or a leap up the career ladder.

Now whether that “something to say” has much to do with reality is another question, as “Ace in the Hole” is a satire of the morally corrupt side of American drive and ingenuity, along with the absurdity of mass gawking. Despite Wilder’s background as a reporter, it presents unusual behavior by Douglas’ reporter, Chuck Tatum.

Interestingly, though dishonesty is later revealed as his core trait, he’s not dishonest in his job interview with Albuquerque Sun-Bulletin editor Mr. Boot (Porter Hall): Tatum admits that in addition to being a drunkard, he lost one job due to a libel suit. The first point wasn’t a deal-breaker in 1951, but it’s wild how Boot brushes over the second one. However, Tatum comes cheap.

“Ace in the Hole” (1951)

Director: Billy Wilder

Writers: Billy Wilder, Lesser Samuels, Walter Newman (screenplay); Victor Desny (story)

Stars: Kirk Douglas, Jan Sterling, Robert Arthur

Douglas plays Tatum as one of those big personalities that could almost draw someone into his gravity well, but it’s a repulsing force in this case, in my view. When Tatum and Jimmy Olsen-esque photographer Herbie (Robert Arthur) come upon a cave-in on the outskirts of their coverage area – where gas-station/restaurant owner Leo Minosa (Richard Benedict) is trapped — Tatum correctly recognizes a story that will sell papers.

As with Tatum’s skimmed-over mention of libel, “Ace” doubles down on its logic hole when Tatum uses his force of personality to extend the time it takes to rescue Leo. It’s a stretch to believe he could manipulate the sheriff and the engineers, and that he could gain exclusive access to information on a public story, but even more of a stretch to suggest he would abandon the core maxim of “Tell the truth” (a slogan found on Boot’s wall).

An extreme case of shaping the narrative

It’s a stretch not because it’s impossible for Tatum to be greedy, driven and manipulative, but because big fakery will be found out, and in journalism that ends your career. It’s not a good field to run a con in. Yes, there have been cases of outright plagiarism in journalism (“Shattered Glass”), but Tatum is not portrayed with any type of naivete, stupidity or mental illness where we’d believe he’d risk abandoning his core value of honesty. (I don’t mean he holds honesty as a personal moral value, I mean honesty has money-making value in his field.)

The story of Leo being rescued the correct way – via bracing the tunnel walls – would be a nice rung on his career climb, but Tatum convinces officials to drill down from the mountaintop, a process that will take a week instead of a day. He’s not merely milking a story, he’s manipulating events.

When viewed as satire, though, “Ace” is often an over-the-top delight. Tatum tries to become a superstar tabloid journalist even though the mainstream-print structure doesn’t desire that, doing his part to turn the desert around the cave-in into a literal carnival, complete with a theme song. (Indeed, the film was released with the weaker title “The Big Carnival.”)

Blending absurdist satire with the tragedy of a man being trapped, “Ace” lacks something predictable at its core, such as a romance. Leo’s wife, Lorraine (Jan Sterling), is bored in New Mexico and sees this event as a chance to leave Leo, and even flirts with Tatum a bit – but he has a one-track mind, with that track heading to a big-city paper.

So I didn’t know precisely where “Ace in the Hole” would go, which is a positive trait. It’s not a particularly resonant newspapering movie, since – for all the issues with journalism in the ensuing 75 years — manipulation of events themselves is not common. (Spin on genuine events is a much easier and safer approach.) On the other hand, it’s a good character study that suggests moral lines have value not just for decent humans but also for con artists.

Wilder Wednesdays looks at the catalog of legendary writer-director Billy Wilder.