“The Lost Weekend” (1945) must have been striking upon its release for its matter-of-fact portrayal of alcoholism. The Forties were the decade of film noir, when private detectives were functioning alcoholics. Any normalcy, let alone glamour, is stripped from alcoholism by writer-director Billy Wilder and star Ray Milland, who achieves the difficult job of portraying this condition without exaggeration, comedy or fakeness.

A not-so-relaxing ‘Weekend’

Based on Charles R. Jackson’s 1944 novel, “The Lost Weekend” is now essentially a genre, referring to any story of someone caught in a spiral of their own bad habits – but, somewhat confusingly to an observer, caused by addiction or brain chemistry they can’t control. As comedian Mitch Hedberg once noted, alcoholism is the only disease people get mad at you for having.

The film, though, isn’t about the frustrations of Don Birnam’s brother Wick (Phillip Terry), girlfriend Helen (Jane Wyman) or bartender Nat (Howard Da Silva), who has that awkward middle position where the customer is always right but he doesn’t want enable someone’s slow suicide.

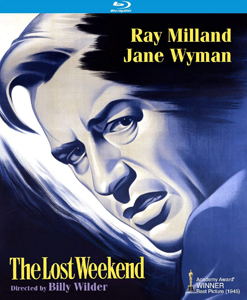

“The Lost Weekend” (1945)

Director: Billy Wilder

Writers: Charles Brackett, Billy Wilder (screenplay); Charles R. Jackson (novel)

Stars: Ray Milland, Jane Wyman, Phillip Terry

“Weekend” instead puts us in the position of Don. We marvel at the way alcohol controls his life, because he increasingly brushes off the things that obviously should come first: a trip with his brother, time with his girl, or even – if he embarks on another vice – a tryst with Gloria (Doris Dowling), a cute patron of Nat’s Bar who speaks in abbreviations and is unaccountably crushing on him. (She might be a figment of his imagination, except that Don retains his movie-star looks even when a mess. The makeup team merely spritzes Milland a bit.)

Instead, he’s all about acquiring the next shot or bottle. Interestingly, to an outside observer it’s often a straightforward matter of buying it, or remembering he placed a quart of rye in his apartment’s light fixture. But because his brain is muddled, he forgets the hiding place. Or, of course, he’s out of money.

At first I thought this was a uniquely 1945 or uniquely cinematic condition of being jobless yet affording an apartment; however, it turns out Wick (the very posture and dress of responsibility and respectability) is letting 33-year-old Don stay with him for free. While Don is unquestionably the core character, “Weekend” does give us a sense of his loved ones’ frustrations. Wick couldn’t be kinder and Helen couldn’t be more patient, yet that’s not working. What is the answer?

Hounded by booze

Later films about people who lose control will take us down deeper, darker, wilder (pun intended) holes. “Prozac Nation” is among my favorites, and the detoxification scene in “French Connection II” is searing, but “Weekend” is pretty dark too. This film’s detox center sequence, where patients experiencing withdrawal are dragged screaming into the “violent ward,” is so iconic that simply seeing a similar multi-bunk detox center – for instance, the one in “Hoosiers” – allows us to fill in the darker blanks.

Wilder mostly makes “Weekend” memorable with a straight-ahead, de-glamorizing approach that shows alcoholism controls the alcoholic. But that’s not to say it’s without style; the apartment and other spaces get murkier as the narrative progresses. Don’s gruesome hallucination scene is daring on a special-effects level, in addition to representing his low point.

Sometimes “Weekend” itself is classified as film noir, but it’s really anti-film noir. Certainly, noir and hardboiled fiction can acknowledge the true nature of alcoholism: It’s the core theme of Raymond Chandler’s “The Long Goodbye” from the next decade. But note that Marlowe retains total control of his drinking; it’s a supporting character who can’t.

Also, film noirs tend to not have happy endings. We might wonder: How much will the Hays Code effect the ending – the acquisition of an “answer” – of Don’s battle against alcohol? What possible answer can there be: Either you force yourself to stop drinking or you don’t. If the script tells us Don just stops, that allows him to survive, but does it really give hope to an alcoholic viewer?

While I wouldn’t necessarily recommend “The Lost Weekend” as a replacement for AA, counseling and medication, it is filled with honesty, and Wilder balances that honesty against the art form’s (and, I admit, viewers’) need for hope. The film is worth toasting … erm, with a non-alcoholic beverage, of course.

Wilder Wednesdays looks at the catalog of legendary writer-director Billy Wilder.